Shchors Nikolai Alexandrovich. Shchors Nikolai Aleksandrovich in the Bryansk region

In the Soviet Union, his name was a legend. Streets and state farms, ships and military formations were named in his honor. Every schoolboy knew the heroic song about how “the commander of the regiment walked under the red banner, his head was tied, blood on his sleeve, a bloody trail spreads over damp grass.” This commander was the famous hero of the Civil War, Nikolai Shchors. In the biography of this man, whom I. Stalin called the "Ukrainian Chapaev", there are quite a few "blank spots" - after all, he even died under very strange and mysterious circumstances. This mystery, which has not been revealed so far, is almost a hundred years old.

In the history of the Civil War 1918-1921. there were many iconic, charismatic figures, especially in the camp of the "winners": Chapaev, Budyonny, Kotovsky, Lazo ... This list can be continued, no doubt including the name of the legendary Red Divisional Commander Nikolai Shchors. It is about him that poems and songs were written, a huge historiography was created, and the famous feature film by A. Dovzhenko “Shchors” was shot 60 years ago. There are monuments to Shchors in Kiev, which he courageously defended, Samara, where he organized the partisan movement, Zhitomir, where he smashed the enemies of the Soviet regime, and near Korosten, where his life was cut short. Although a lot has been written and said about the legendary commander, the history of his life is full of mysteries and contradictions, over which historians have been struggling for decades. The biggest secret in the biography of the division chief N. Shchors is connected with his death. According to official documents, the former lieutenant of the tsarist army, and then the legendary red commander of the 44th Infantry Division, Nikolai Shchors, died from an enemy bullet in the battle near Korosten on August 30, 1919. However, there are other versions of what happened ...

Nikolai Shchors, a native of Snovsk Gorodnyanskosh district, in his short life, and he lived only 24 years, managed a lot - he graduated from a military paramedic school in Kiev, took part in the First World War (after graduating from the cadet school evacuated from Vilna in Poltava, Shchors was sent to the Southwestern Front as a junior company commander), where, after difficult months of trench life, he developed tuberculosis. During 1918-1919. the former warrant officer of the tsarist army made a dizzying career - from one of the commanders of the small Semenovsky Red Guard detachment to the commander of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division (from March 6, 1919). During this time, he managed to be the commander of the 1st regular Ukrainian regiment of the Red Army named after I. Bohun, the commander of the 2nd brigade of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division, the commander of the 44th rifle division and even the military commandant of Kiev.

In August 1919, the 44th Streltsy Division of Shchors (the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Division joined it), which was part of the 12th Army, held positions at a strategically important railway junction in the city of Korosten west of Kiev. With the last of their strength, the fighters tried to stop the Petliurists, who at all costs tried to take over the city. When on August 10, as a result of a raid by the Don Cavalry Corps under General Mamontov, the Cossacks broke through the Southern Front and set off towards Moscow along its rear, the 14th Army, which had taken the main blow, began to hastily retreat. Between the whites and the reds, only the Shchors division, which was fairly battered in battles, now remained. However, the fact that Kyiv could not be defended was clear to everyone, it was considered only a matter of time. The Reds had to hold out in order to evacuate institutions, organize and cover the retreat of the 12th Army of the Southern Front. Nikolai Shchors and his fighters managed to do it. But they paid a high price for it.

On August 30, 1919, divisional commander N. Shchors arrived at the location of the Bogunsky brigade near the village of Beloshitsa (now Shchorsovka) near Korosten and died on the same day from a fatal wound to the head. The official version of the death of N. Shchors was as follows: during the battle, the divisional commander watched the Petliurists from binoculars, while listening to the reports of the commanders. His fighters went on the attack, but suddenly an enemy machine gun came to life on the flank, the burst of which pressed the Red Guards to the ground. At this moment, the binoculars fell out of the hands of Shchors; he was mortally wounded and died 15 minutes later in the arms of his deputy. Witnesses of the mortal wound confirmed the heroic version of the death of the beloved commander. However, from them, in an unofficial setting, there was also a version that the bullet was fired by one of their own. To whom was it beneficial?

In that last battle, there were only two people in the trench next to Shchors - assistant commander I. Dubova and another rather mysterious person - a certain P. Tankhil-Tankhilevich, a political inspector from the headquarters of the 12th Army. Major General S.I. Petrikovsky (Petrenko), who at that time commanded the 44th cavalry brigade of the division, although he was nearby, ran up to Shchors when he was already dead and his head was bandaged. Dubovoy claimed that the division commander was killed by an enemy machine gunner. However, it is surprising that immediately after the death of Shchors, his deputy ordered the dead head to be bandaged and forbade the nurse, who ran from a nearby trench, to unbandage it. It is also interesting that the political inspector lying on the right side of Shchors was armed with a Browning. In his memoirs, published in 1962, S. Petrikovsky (Petrenko) cited Dubovoy's words that during the skirmish, Tankhil-Tankhilevich, contrary to common sense, shot at the enemy from a Browning. One way or another, but after the death of Shchors, no one else saw the staff inspector, traces of him were already lost in the first days of September 1919. It is interesting that he also got to the front line of the 44th division under unclear circumstances by order of S.I. Aralov, a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army, as well as the head of the intelligence department of the Field Headquarters of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic. Tankhil-Tankhilevich was a confidant of Semyon Aralov, who hated Shchors "for being too independent." In his memoirs, Aralov wrote: "Unfortunately, persistence in personal conversion led him (Shchors) to an untimely death." With his intractable character, excessive independence, and recalcitrance, Shchors interfered with Aralov, who was a direct protege of Leon Trotsky and therefore was endowed with unlimited powers.

There is also an assumption that Shchors' personal assistant I. Dubova was accomplices in the crime. General S.I. Petrikovsky insisted on this, to whom he wrote in his memoirs: “I still think that the political inspector fired, and not Dubova. But without the assistance of Dubovoy, the murder could not have happened ... Only relying on the assistance of the authorities in the person of Deputy Shchors Dubovoy, on the support of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army, the criminal [Tankhil-Tankhilevich] committed this terrorist act ... I knew Dubovoy not only from the Civil War. He seemed like an honest man to me. But he also seemed weak-willed to me, without special talents. He was nominated, and he wanted to be nominated. That's why I think he was made an accomplice. And he did not have the courage to prevent the murder.”

Some researchers argue that the order to liquidate Shchors was given by the people's commissar and head of the Revolutionary Military Council L. Trotsky, who liked to purge among the commanders of the Red Army. The version associated with Aralov and Trotsky is considered by historians to be quite probable and, moreover, consistent with the traditional perception of Trotsky as the evil genius of the October Revolution.

According to another assumption, the death of N. Shchors was also beneficial to the "revolutionary sailor" Pavel Dybenko, a more than well-known personality. The husband of Alexandra Kollontai, an old party member and friend of Lenin, Dybenko, who at one time held the post of head of the Central Balt, provided the Bolsheviks with detachments of sailors at the right time. Lenin remembered and appreciated this. Dybenko, who had no education and was not distinguished by special organizational skills, was constantly promoted to the most responsible government posts and military posts. He, with invariable success, failed the case wherever he appeared. First, he missed P. Krasnov and other generals, who, having gone to the Don, raised the Cossacks and created a white army. Then, commanding a sailor detachment, he surrendered Narva to the Germans, after which he not only lost his position, but also lost his party card. Failures continued to haunt the former Baltic sailor. In 1919, while holding the post of commander of the Crimean army, the local people's commissar for military and naval affairs, as well as the head of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Crimean Republic, Dybenko surrendered Crimea to the Whites. Soon, however, he led the defense of Kyiv, which he mediocrely failed and fled the city, leaving Shchors and his fighters to their fate. Returning to his possible role in the murder of Shchors, it should be noted that as a person who came out of poverty and managed to get a taste of power, Dybenko was terrified of another failure. The loss of Kyiv could be the beginning of his end. And the only person who knew the truth about how Dybenko “successfully” defended Kyiv was Shchors, whose words could be heeded. He knew all the ups and downs of these battles thoroughly and, moreover, had authority. Therefore, the version that Shchors was killed on the orders of Dybenko does not seem so incredible.

But this is not the end. There is another version of the death of Shchors, which, however, hardly casts doubt on all the previous ones. According to her, Shchors was shot by his own guard out of jealousy. But in the collection "The Legendary Commanding Officer", published in September 1935, in the memoirs of Shchors's widow, Fruma Khaikina-Rostova, the fourth version of his death is given. Khaikina writes that her husband died in battle with the White Poles, but does not provide any details.

But the most incredible assumption, which is associated with the name of the legendary division commander, was expressed on the pages of the Moscow weekly Sovremennik, popular during the time of "perestroika and glasnost". An article published in 1991 in one of his issues was truly sensational! It followed from it that the divisional commander Nikolai Shchors did not exist at all. The life and death of the red commander is supposedly another Bolshevik myth. And its origin began with the well-known meeting of I. Stalin with artists in March 1935. It was then that the head of state allegedly turned to A. Dovzhenko with the question: “Why do the Russian people have the hero Chapaev and a film about the hero, but the Ukrainian people do not have such a hero?” Dovzhenko, of course, instantly understood the hint and immediately set to work on the film. As the heroes, according to Sovremennik, they appointed the unknown Red Army soldier Nikolai Shchors. In fairness, it should be noted that the meeting of the Soviet leadership with cultural and art workers in 1935 really took place. And it was precisely from 1935 that the all-Union glory of Nikolai Shchors began to actively grow. The Pravda newspaper in March 1935 wrote about this: “When the director A.P. Dovzhenko was awarded the Order of Lenin at a meeting of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and he returned to his place, he was overtaken by the remark of Comrade Stalin: “Your debt is Ukrainian Chapaev” . Some time later, at the same meeting, Comrade Stalin asked Comrade Dovzhenko questions: “Do you know Shchors?” “Yes,” Dovzhenko replied. "Think about him," said Comrade Stalin. There is, however, another - absolutely incredible - version, which was born in "near-cinema" circles. Until now, the legend roams the corridors of GITIS (now RATI) that Dovzhenko began filming his heroic revolutionary film not at all about Shchors, but about V. Primakov, even before the arrest of the latter in 1937 in the case of the military conspiracy of Marshal Tukhachevsky. Primakov was the commander of the Kharkov Military District and was a member of the party and state elite of Soviet Ukraine and the USSR. However, when the investigation into the Tukhachevsky case began, A. Dovzhenko began to re-shoot the movie - now about Shchors, who by no means could be involved in conspiratorial plans against Stalin for obvious reasons.

When the Civil War ended and memoirs of participants in the military and political struggle in Ukraine began to be published, the name of N. Shchors was always mentioned in these stories, but not among the main figures of the era. These places were reserved for V. Antonov-Ovseenko as the organizer and commander of the Ukrainian Soviet armed forces and then the Red Army in Ukraine; Commander V. Primakov, who suggested the idea of creating and commanded units and formations of the Ukrainian "Red Cossacks" - the first military formation of the Council of People's Commissars of Ukraine; S. Kosior, a high party leader who led the partisan movement in the rear of the Petliurists and Denikinists. All of them in the 1930s. were prominent party members, held high government positions, represented the USSR in the international arena. But during the Stalinist repressions of the late 1930s. these people were ruthlessly exterminated. About who I. Stalin decided to fill the empty niche of the main characters of the struggle for Soviet power and the creation of the Red Army in Ukraine, the country learned in 1939, when the Dovzhenko film “Shchors” was released. The very next day after its premiere, the lead actor E. Samoilov woke up popularly famous. At the same time, no less fame and official recognition came to Shchors, who had died twenty years earlier. Such a hero as Shchors, young, brave in battle and fearlessly killed by an enemy bullet, successfully “fitted” into the new format of history. However, now the ideologists face a strange problem, when there is a hero who died in battle, but there is no grave. For official canonization, the authorities ordered to urgently find the burial of Nikolai Shchors, which no one has remembered so far.

It is known that in early September 1919, the body of Shchors was taken to the rear - to Samara. But only 30 years later, in 1949, the only witness to the rather strange funeral of the divisional commander was found. It turned out to be a certain Ferapontov, who, as a homeless boy, helped the caretaker of the old cemetery. He told how late in the autumn evening a freight train arrived in Samara, from which they unloaded a sealed zinc coffin, which was very rare at that time. Under the cover of darkness, keeping secrecy, the coffin was brought to the cemetery. After a short “funeral meeting”, a three-time revolver salute sounded and the grave was hastily covered with earth, setting up a wooden tombstone. The city authorities did not know about this event and no one looked after the grave. Now, after 30 years, Ferapontov led the commission to the burial place ... on the territory of the Kuibyshev cable plant. Shchors' grave was found under a half-meter layer of gravel. When the hermetically sealed coffin was opened and the remains were exhumed, the medical commission that conducted the examination concluded that “the bullet entered the back of the head and exited through the left parietal bone.” “It can be assumed that the bullet was revolver in diameter ... The shot was fired at close range,” it was written in the conclusion. Thus, the version of the death of Nikolai Shchors from a revolver shot fired from a distance of only a few steps was confirmed. After a thorough study, the ashes of N. Shchors were reburied in another cemetery and finally a monument was erected. The reburial was carried out at a high government level. Of course, materials about this were kept for many years in the archives of the NKVD, and then the KGB under the heading "Secret", they were made public only after the collapse of the USSR.

Like many commanders of the Civil War, Nikolai Shchors was only a "bargaining chip" in the hands of the powers that be. He died at the hands of those for whom their own ambitions and political goals were more important than human lives. These people did not care that, left without a commander, the division had practically lost its combat capability. As the hero of the Civil War and a former member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Ukrainian Front E. Shadenko said, “only enemies could tear Shchors away from the division, into whose consciousness he had grown roots. And they tore it off."

V. M. Sklyarenko, I. A. Rudycheva, V. V. Syadro. 50 famous mysteries of the history of the XX century

Nikolai Alexandrovich Shchors (May 25 (June 6), 1895 - August 30, 1919) - a wartime officer of the Russian Imperial Army, commander of the Ukrainian rebel formations, head of the Red Army division during the Civil War in Russia, a member of the Communist Party since the autumn of 1918 (before that he was close to the Left SRs).

Biography

Youth

Born and raised in the village of Snovsk, Velikoshchimelsky volost, Gorodnyansky district, Chernigov province (since 1924 - the city of Snovsk, now the regional center of Shchors, Chernihiv region, Ukraine) in a large family of a railway worker.

In July 1914 he graduated from the military paramedic school in Kyiv.

World War I

On August 1, 1914, the Russian Empire entered the First World War and Nikolai was appointed to the post of military paramedic of an artillery regiment as a volunteer. In 1914-1915 he took part in the fighting on the North-Western Front.

At the end of October 1915, 20-year-old Shchors N.A. was assigned to active military service and transferred as a private to a reserve battalion. In January 1916, he was sent to a four-month crash course at the Vilna Military School, which by that time had been evacuated to Poltava. Then, with the rank of warrant officer, he served as a junior company officer in the 335th Anapa Infantry Regiment of the 84th Infantry Division, which operated on the Southwestern and Romanian fronts. In April 1917 he was awarded the rank of second lieutenant (seniority from February 1, 1917).

During the war, Nikolai fell ill with an open form of tuberculosis and in May 1917 was sent for treatment to Simferopol, to a military hospital. In Simferopol, attending rallies of soldiers of the reserve regiment, he joins the revolutionary movement.

After the October Revolution, on December 30, 1917, Shchors was released from military service due to illness and left for his homeland in Snovsk.

Civil War

In March 1918, in connection with the occupation of the Chernigov province by German troops, Shchors with a group of comrades left Snovsk for Semyonovka and led the united insurgent partisan detachment of the Novozybkovsky district there, which participated in March - April 1918 in battles with the invaders in the Zlynka, Klintsov area.

Under the onslaught of superior enemy forces, the partisan detachment retreats to the territory of Soviet Russia and in early May 1918 is interned by the Russian authorities. Shchors goes to Samara, then to Moscow. He takes part in the revolutionary movement, gets acquainted with the leaders of the Bolsheviks and the Left Social Revolutionaries.

In Moscow, he makes an attempt to enter the medical faculty of Moscow University, providing a fake certificate of graduation from the Poltava Theological Seminary, which gives the right to enter the university, however, having met his acquaintance Kazimir Kvyatek, he changes his mind and goes with him to Kursk, at the disposal of the All-Ukrainian Central Military Commission. With the mandate of the VUTsVRK at the end of August 1918, he arrives in the neutral zone (in the village of Yurinovka) to the chief of staff of the insurgent sector Unecha-Zernovo Petrikovsky-Petrenko S.I.

The territory occupied by the troops of Germany and Austria-Hungary in March-April 1918

In September 1918, on the instructions of the All-Ukrainian Central Military Revolutionary Committee, in the Unecha region, in the neutral zone between the German occupation forces and Soviet Russia, he formed the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Regiment named after P.I. Bohun, who became part of the 1st Ukrainian Insurgent Division under the command of Krapivyansky N. G.

By order of the All-Ukrainian Central Military Revolutionary Committee (VTsVRK) of September 22, 1918, Shchors was appointed commander of the "Ukrainian revolutionary regiment named after comrade Bohun", in October - commander of the 2nd brigade as part of the Bohunsky and Tarashchansky regiments of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division , which liberated Chernigov, Kiev, Fastov. According to V. A. Antonov-Ovseenko, the Red Army men loved Shchors for his diligence and courage, the commanders respected him for his intelligence, clarity and resourcefulness.

On February 5, 1919, 23-year-old Nikolai Shchors was appointed commandant of Kyiv and, by decision of the Provisional Workers' and Peasants' Government of Ukraine, was awarded an honorary golden weapon.

The rebuke of "ataman" Shchors to "pan-hetman" Petliura, 1919

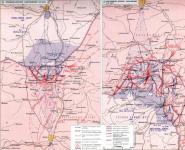

From March 6 to August 15, 1919, Shchors commanded the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Division, which, during a swift offensive, recaptured Zhytomyr, Vinnitsa, Zhmerinka from the Petliurists, defeated the main forces of the UNR in the area of Sarny - Rivne - Brody - Proskurov, and then in the summer of 1919 defended in the region of Sarny - Novograd-Volynsky - Shepetovka from the troops of the Polish Republic and the Petliurists, but was forced to retreat to the east under pressure from superior forces.

In May 1919, Shchors did not support the Grigoriev uprising.

On August 15, 1919, during the reorganization of the Ukrainian Soviet divisions into regular units and formations of the unified Red Army, the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division under the command of N. A. Shchors was merged with the 3rd border division under the command of I. N. Dubovoy, becoming 44th Rifle Division of the Red Army. On August 21, Shchors was appointed head of the division, and Dubovoy was appointed deputy head of the division. The division consisted of four brigades.

The division stubbornly defended the Korosten railway junction, which ensured the evacuation of Kyiv (on August 31, the city was taken by the Volunteer Army of General Denikin) and the exit from the encirclement of the Southern Group of the 12th Army.

On August 30, 1919, in a battle with the 7th brigade of the 2nd corps of the Galician army near the village of Beloshitsa (now the village of Shchorsovka, Korostensky district, Zhytomyr region, Ukraine), while in the advanced chains of the Bogunsky regiment, Shchors was killed by a bullet in the back of the head under unclear circumstances.

Shchors' body was transported to Samara, where he was buried at the Orthodox All-Saints Cemetery (now the territory of the Samara Cable Company). According to one version, he was taken to Samara, as the parents of his wife Fruma Efimovna lived there.

In 1949, the remains of Shchors were exhumed in Kuibyshev. On July 10, 1949, in a solemn ceremony, the ashes of Shchors were reburied at the Kuibyshev city cemetery. The body was found well-preserved, practically incorrupt, although it had lain in a coffin for 30 years. This is explained by the fact that when Shchors was buried in 1919, his body was previously embalmed, soaked in a steep solution of table salt and placed in a sealed zinc coffin. By 1954, when the 300th anniversary of the reunification of Russia and Ukraine was celebrated, a granite obelisk was installed on the grave. Architect - Alexey Morgun, sculptor - Alexey Frolov.

Doom studies

The official version that Shchors died in battle from a bullet of a Petlyura machine gunner began to be criticized with the onset of the “thaw” of the 1960s.

Initially, the researchers charged the murder of the commander only to the former commander of the Kharkov military district, Ivan Dubovoi, who during the Civil War was Nikolai Shchors's deputy in the 44th division. In the 1935 collection "Legendary Chief Division" Ivan Dubovoy's testimony is placed:

Nick opened strong machine-gun fire and, I especially remember, one machine gun at the railway booth showed "daring" ... Shchors took binoculars and began to look where the machine-gun fire came from. But a moment passed, and the binoculars from the hands of Shchors fell to the ground, Shchors' head too ... ".

The head of the mortally wounded Shchors was bandaged by Oak. Shchors died in his arms. “The bullet entered from the front,” writes Dubovoy, “and exited from behind,” although he could not help but know that the entrance bullet hole was smaller than the exit one. When the nurse of the Bogunsky regiment, Anna Rosenblum, wanted to change the first, very hasty bandage on the head of the already dead Shchors to a more accurate one, Dubovoy did not allow it. By order of Oak, the body of Shchors was sent for burial many thousands of miles away to Russia, to Samara, without a medical examination. Witness to the death of Shchors was not only Oak. Nearby were the commander of the Bogunsky regiment, Kazimir Kvyatek, and the authorized representative of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army, Pavel Tankhil-Tankhilevich, sent with an inspection by a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army, Semyon Aralov.

The likely perpetrator of the murder of the red commander is Pavel Samuilovich Tankhil-Tankhilevich. He was twenty-six years old, he was born in Odessa, graduated from high school, spoke French and German. In the summer of 1919 he became a political inspector of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army. Two months after the death of Shchors, he left Ukraine and arrived on the Southern Front as a senior censor-controller of the Military Censorship Department of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 10th Army.

The exhumation of the body, carried out in 1949 in Kuibyshev during the reburial, confirmed that Nikolai Shchors was killed at close range by a shot in the back of the head (the analysis of the exhumation data took place after Stalin's death, with the approval of Khrushchev).

On July 27, 1919, brigade commander of the 44th division Anton Bogunsky was shot without trial or investigation. On August 11, 1919, near Rovno, during a mutiny, under unclear circumstances, Shchorsovite Timofey Chernyak, commander of the Novgorod-Seversk brigade, was killed. On August 21, 1919, Vasily Bozhenko, the commander of the Tarashcha brigade, died suddenly in Zhytomyr (according to some reports, he was poisoned, according to the official version, he died of pneumonia). All of them were the closest associates of Nikolai Shchors.

Family

Wife - Rostova-Shchors, Fruma Efimovna.

Daughter - Valentina Nikolaevna Shchors, married to the theoretical physicist I.M. Khalatnikov.

Memory

Monument to N. A. Shchors in Zhitomir (1932)

Memorial sign in honor of N. A. Shchors (1981) in Belgorod.

A monument was erected on the grave of Shchors in Kuibyshev (1953). Also in Kuibyshev in the 1980s, a granite bust of N. Shchors was installed.

Equestrian monument to Shchors in Kyiv (erected in 1954).

In the USSR, the publishing house "IZOGIZ" issued a postcard with the image of N. Shchors.

In 1944, a postage stamp of the USSR dedicated to Shchors was issued.

In 1935, the city of Snovsk, Chernihiv region, was renamed Shchors.

The village of Shchorsa in the Bratsk district of the Nikolaev region.

Shchorsovka villages in Zhytomyr, Poltava and Kherson regions.

The village of Shchorsovo in the Nikolaev and Odessa regions.

The urban-type settlement of Shchorsk in the Krinichansky district of the Dnepropetrovsk region.

Shchors is the former name of the village of Nauryzbai Batyr in the Akmola region of Kazakhstan.

In the city of Bryansk and Unecha, Bryansk region, a monument was erected to Shchors.

Streets in the following cities are named after him: Adler, Aznakayevo, Kaliningrad, Tula, Vladikavkaz, Velikie Luki, Abakan, Slavyansk-on-Kuban, Belgorod, Dzhankoy, Mineralnye Vody, Chernihiv, Kiev, Simferopol, Zaporozhye, Konstantinovka, Lutsk, Nikolaev, Sumy , Khmelnitsky, Balakovo, Berdichev, Bykhov, Nakhodka, Novaya Kakhovka, Korosten, Krivoy Rog, Moscow, Ivanovo, Ivanteevka, Dnepropetrovsk, Baku, Yalta, Grodno, Dudinka, Kirov, Krasnoyarsk, Donetsk, Vinnitsa, Odessa, Orsk, Brest, Vitebsk , Podolsk, Voronezh, Krasnodar, Stavropol, Novorossiysk, Tuapse, Minsk, Bryansk, Kalach-on-Don, Konotop, Izhevsk, Irpen, Tomsk, Zhitomir, Ufa, Yekaterinburg, Nizhny Tagil, Smolensk, Safonovo, Tver, Yeysk, Bogorodsk, Tyumen, Buzuluk, Saratov, Irkutsk, Engels, Chuguev, Saransk, Lugansk, Ryazan, Kuznetsk, Upper Pyshma, Astana, Novocherkassk, Taganrog, Kremenchug, Dzerzhinsk (Nizhny Novgorod region), Belaya Tserkov, Klintsy, Yaroslavl, Unecha, Izmail; a children's park in Samara (founded on the site of the former All Saints cemetery), a park in Lugansk.

From 1941 to 1991, the Small Avenue of the Petrograd side in St. Petersburg was called Shchors Avenue.

In the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), in the city of Yakutsk, one of the lakes is named after Shchors.

The name was given to the Leningrad Military Medical School.

The name was given to the Zaporozhye Regional Ukrainian Music and Drama Theatre.

Postage stamp of the USSR, 1944

Monument on the grave of Shchors in Samara, erected in 1954

Equestrian monument to Shchors in Kyiv, erected in 1954 on Taras Shevchenko Boulevard

Monument to N. Shchors in Chernihiv

Until 1935, the name of Shchors was not widely known, even the Great Soviet Encyclopedia did not mention him. In February 1935, presenting Alexander Dovzhenko with the Order of Lenin, Stalin suggested that he make a film about the "Ukrainian Chapaev", which was done. Later, several books, songs, even an opera were written about Shchors, schools, streets, villages and even a city were named after him. In 1936, Matvey Blanter (music) and Mikhail Golodny (lyrics) wrote "Song of Shchors":

The detachment was walking along the shore,

Went from afar

Went under the red flag

Regiment commander.

The head is tied

Blood on my sleeve

A trail of bloody creeps

On wet grass.

"Whose lads will you be,

Who will lead you into battle?

Who is under the red banner

Is the wounded man coming?"

"We are the sons of laborers,

We are for a new world

Shchors goes under the banner -

Red commander.

In hunger and cold

His life has passed

But not in vain shed

His blood was.

Thrown behind the cordon

fierce enemy,

Tempered from youth

Honor is dear to us."

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian rock band Mango-Mango performed the Song of Shchors with a modified text.

Bibliography

Dubovoi I. N. My memories of Shchors. - K .: On Varti, 1935.

Karpenko V. Shchors, M., 1974.

Civil war in Ukraine 1918-1920. Sat. documents and materials. T. 1 (book 1) - 2. Kyiv, 1967.

Bovtunov A. T. The knot of Slavic friendship. Essay on the collectives of enterprises of the Unecha railway junction. Publishing house of the Klintsov printing house, 1998. 307 p.

Julius Kim, Three stories from the cycle "Once upon a time Mikhailov ..." // "Continent" 2003, No. 117

Y. Safonov. A documentary story about the "mysterious" death of Nikolai Shchors // "Lenin's Banner" (now "Unechskaya Gazeta") No. 95-111 for 1991.

Who killed the legendary division commander Nikolai Shchors?

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Nikolai Alexandrovich Shchors (May 25 (June 6), 1895 - August 30, 1919) - officer of the Russian Imperial Army of wartime (second lieutenant), commander of the Ukrainian rebel formations, head of the Red Army during the Civil War in Russia, member of the Communist Party since 1918 (before that was close to the Left SRs).

Biography

Born and raised in the village of Korzhovka, Velikoschimelsky volost, Gorodnyansky district, Chernihiv province (since 1924 - Snovsk, now the regional center of the city of Shchors, Chernihiv region of Ukraine) in the family of a railway worker.

In 1914 he graduated from the military paramedic school in Kyiv. On August 1, 1914, the Russian Empire entered the First World War. Nikolai went to the front as a volunteer military paramedic.

Civil War

In March - April 1918, Shchors led the united insurgent partisan detachment of the Novozybkovsky district, which, as part of the 1st revolutionary army, participated in battles with the German invaders.

In September 1918, in the Unecha region, he formed the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Regiment named after P.I. Bohun. In October - November, he commanded the Bogunsky regiment in battles with the German invaders and hetmans, from November 1918 - the 2nd brigade of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division (Bogunsky and Tarashchansky regiments), which liberated Chernihiv, Kiev and Fastov from the troops of the Directory of the Ukrainian People's Republic.

On February 5, 1919, 23-year-old Nikolai Shchors was appointed commandant of Kyiv and, by decision of the Provisional Workers' and Peasants' Government of Ukraine, was awarded an honorary revolutionary weapon.

Front in December 1919

From March 6 to August 15, 1919, Shchors commanded the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Division, which, during a swift offensive, recaptured Zhytomyr, Vinnitsa, Zhmerinka from the Petliurists, defeated the main forces of the Petliurists in the area of Sarny - Rivne - Brody - Proskurov, and then in the summer of 1919 defended in the region of Sarny - Novograd-Volynsky - Shepetovka from the troops of the Polish Republic and the Petliurists, but was forced to retreat to the east under pressure from superior forces.

On August 15, 1919, during the reorganization of the Ukrainian Soviet divisions into regular units and formations of the unified Red Army, the 1st Ukrainian Soviet division under the command of N. A. Shchors was merged with the 44th border division under the command of I. N. Dubovoy, becoming 44th Rifle Division of the Red Army. On August 21, Shchors became her head, and Dubova became the deputy head of the division. The division consisted of four brigades.

The division stubbornly defended the Korosten railway junction, which ensured the evacuation of Kyiv (on August 31, the city was taken by the Volunteer Army of General Denikin) and the exit from the encirclement of the Southern Group of the 12th Army.

On August 30, 1919, in a battle with the 7th brigade of the 2nd corps of the Ukrainian Galician Army near the village of Beloshitsa (now the village of Shchorsovka, Korostensky district, Zhytomyr region, Ukraine), while in the forward chains of the Bogunsky regiment, Shchors was killed under unclear circumstances. He was shot in the back of the head at close range, presumably from 5-10 paces.

The likely perpetrator of the murder of the red commander is Pavel Samuilovich Tankhil-Tankhilevich. He was twenty-six years old, he was born in Odessa, graduated from high school, spoke French and German. In the summer of 1919 he became a political inspector of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 12th Army. Two months after the death of Shchors, he left Ukraine and arrived on the Southern Front as a senior censor-controller of the Military Censorship Department of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 10th Army.

Interesting Facts

The rebuke of "ataman" Shchors to "pan-hetman" Petliura, 1919

Until 1935, the name of Shchors was not widely known, even the TSB did not mention him. In February 1935, presenting Alexander Dovzhenko with the Order of Lenin, Stalin suggested that the artist create a film about the "Ukrainian Chapaev", which was done. Later, several books, songs, even an opera were written about Shchors, schools, streets, villages and even a city were named after him. In 1936, Matvey Blanter (music) and Mikhail Golodny (lyrics) wrote "Song of Shchors":

The detachment was walking along the shore,

Went from afar

Went under the red flag

Regiment commander.

The head is tied

Blood on my sleeve

A trail of bloody creeps

On wet grass.

"Boys, whose will you be,

Who will lead you into battle?

Who is under the red banner

Is the wounded man coming?"

"We are the sons of laborers,

We are for a new world

Shchors goes under the banner -

Red commander.

In hunger and cold

His life has passed

But not in vain shed

His blood was.

Thrown behind the cordon

fierce enemy,

Tempered from youth

Honor is dear to us."

Like many commanders of the Civil War, Nikolai Shchors was only a "bargaining chip" in the hands of the powers that be. He died at the hands of those for whom their own ambitions and political goals were more important than human lives. These people did not care that, left without a commander, the division had practically lost its combat capability. As the hero of the Civil War and a former member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Ukrainian Front E. Shadenko said, “only enemies could tear Shchors away from the division, into whose consciousness he had grown roots. And they tore it off."

V. M. Sklyarenko, I. A. Rudycheva, V. V. Syadro. 50 famous mysteries of the history of the XX century

Nikolai Shchors was one of the brightest representatives of the "new wave" of commanders of the regular Red Army. To what extent the results of the victory of the Red Army would satisfy this independent, charismatic personality, this is another, difficult question. People of a completely different plan took advantage of its fruits - Stalin, Trotsky (they were still formally together), Voroshilov, Budyonny. Heroes or anti-heroes of the Civil War (on the part of the "winners"), for the most part, did not survive the repressions of the 30s

Sergey MAKHUN, "The Day", (Kyiv - Shchors, Chernihiv region - Kyiv)

The purpose of this article is to find out how the vile murder of the hero of the Civil War NIKOLAY SHCHORS is embedded in his FULL NAME code.

Watch in advance "Logicology - about the fate of man".

Consider the FULL NAME code tables. \If there is a shift in numbers and letters on your screen, adjust the image scale.

26 41 58 76 90 100 111 126 138 139 149 150 162 168 179 197 198 212 217 234 249 252 262 286

SCH O R S N I K O L A Y A L E X A N D R O V I C

286 260 245 228 210 196 186 175 160 148 147 137 136 124 118 107 89 88 74 69 52 37 34 24

14 24 35 50 62 63 73 74 86 92 103 121 122 136 141 158 173 176 186 210 236 251 268 286

N I K O L A Y A L E X A N D R O V I C H S O R S

286 272 262 251 236 224 223 213 212 200 194 183 165 164 150 145 128 113 110 100 76 50 35 18

Readers familiar with my articles on assassination attempts and traumatic brain injuries will immediately notice that this article also deals with shooting in the head. In particular, speaking about this, such figures as:

103 = SHOT. 50 = HEAD. 139 = BRAIN, etc.

Let's decipher individual words and sentences:

SCHORS = 76 = WEAPON, DESTROYED.

NIKOLAI ALEKSANDROVICH \u003d 210 \u003d 154-SHOT + 56-DIED.

The number 154 is between the numbers 148 = BREAKED THE SKULL and 160 = BLOOD IS GOING TO THE BRAIN, and the number 56 is in the word NICHOLAS between the numbers 50 = HEAD and 62 = ON THE SPOT.

210 - 76 = 134 = PASSED OUT OF LIFE.

SCHORS NIKOLAI = 149 = DEADLY, KILLED INSTANTLY.

ALEKSANDROVICH \u003d 137 \u003d DOOMED, MURDERING, INSTANT \ I am death \.

149 - 137 \u003d 12 \u003d L \ detail \.

ALEKSANDROVICH SCHORS = 213 = DEATH COME.

NIKOLAI \u003d 73 \u003d BREAKED, BEND.

213 - 73 = 140 = HEAD WOUND.

From the three words received, we make sentences corresponding to the "scenario" embedded in the FULL NAME code:

286 = 134-PASSED + 12 + 140-HEAD WOUND = 134-PASSED + 152-\ 12 + 140 - HEAD PUNCH.

286 = 140 - HEAD WOUND + 146 - \ 134 + 12 \ - BLEEDING, BLOWED BY A BULLET.

Code DATE OF DEATH: 08/30/1919. This is = 30 + 08 + 19 + 19 = 76 = DESTROYED.

DEATH DAY code = 115-THIRTY, FATAL + AUGUST 66, NON-LIFE, CUSTOMIZED = 181 = BULLET BRAIN TEST = TERMINATION OF LIFE.

Code of FULL DATE OF DEATH = 181-THIRTH OF AUGUST + 38-KHAN, MURDER \ n \-\ 19 + 19 \-\ YEAR OF DEATH code \ = 219 = DEATH.

286 \u003d 219 + 67 - DIED.

Code of COMPLETE YEARS OF LIFE = 86-TWENTY, WILL DIE + 100-FOUR, OVERVIEW = 186 = 82-SHOT + 104-KILLED = KILLED BY A BULLET IN POINT.

286 \u003d 186-TWENTY-FOUR + 100-OLD.

186-TWENTY-FOUR - 100-SUSPENDED = 86 = DIE.

Shchors Nikolai Alexandrovich in Bryansk region

N. A. Shchors, as a remarkable organizer and commander of the first detachments of the Red Army, began his activity on the territory of the Novozybkovsky, Klintsovsky, Unechsky regions, which in 1918 were part of Ukraine.

When the "Austro-German troops, which included 41 corps, began to attack Novozybkov from Gomel, dozens of Red Guard and partisan detachments of workers and peasants led by the communists rose to meet them: One of such detachments led by N. A. Shchors arrived in the village of Semyonovka, Iovozybkovsky district.Having united with the Semenovsky partisan detachment, Shchors made an attempt to detain the Germans in Zlynka.

After a heavy battle, under the command of Shchors, a small group of fighters shriveled. But that didn't stop him. Having replenished the detachment with new volunteers in Novozybkovo with the help of the city party organization, Shchors continued the fight against the aeyevYiyi. okkup "amtami. Holding back their offensive, he fought back from Novo-zybkov to Klintsy and further to Unecha - to the border of Soviet Russia,

After the very first battles with the Germans, Shchors realized that it was impossible to fight the enemy’s regular troops armed to the teeth, “having small scattered small partisan detachments. He begins to create regular units of the Red Army from partisan detachments.

In September 1918, in Unecha, he organized the First Ukrainian Soviet Insurgent Regiment named after Bohun (Bogun Regiment) from partisan masses. Shchors prepared the regiment for an offensive to support the popular uprising that had intensified in Ukraine. At the same time, he established contact with the partisan detachments operating in the forests of the Chernihiv region. Through Shchors there was help from Soviet Russia to the struggling Ukraine.

Not far from the location of the Bogunsky regiment, several more rebel regiments were formed from partisan detachments at the same time. In the village of Seredina-Buda, the Kiev carpenter Vasily Bozhenko formed the Tara-Shansky regiment. And in the forests east of Novgorod-Seversk, the Novgorod-Seversky regiment was formed. All these regiments later merged into the First Ukrainian Insurgent Division.

The revolution in Germany somewhat changed the situation. In Unecha, at the headquarters of the Bogunsky regiment, a delegation of soldiers from the German garrison from the village of Lyschich and, bypassing her command, began negotiations on the evacuation of her units. A rally was organized at the Unecha station, which was attended by delegates, local communists, fighters of the Bogunsky regiment and other military units. Shchors sent a telegram to Moscow addressed to V. I. Lenin, V which he reported that a delegation with music, banners, with the Bogunsky regiment in full combat strength went on the morning of November 13, to a demonstration beyond the demarcation line with. Lyschichy and in Kustichi Vryanovy, from where representatives from the German units arrived.

No longer relying on their soldiers, the German command began to hastily replace them with Russian White Guards and Ukrainian nationalists. Petlyura, the strangler of freedom, swam out again to Siena. This created a great danger for the revolution. A quick offensive against the enemies of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples was necessary.

At this time, a powerful popular uprising began in Ukraine. On November 11, the Council of People's Commissars, chaired by V. j. Lenin gave the command of the Red Army a directive: within ten days to begin (an offensive to support the insurgent workers and peasants in Ukraine. On November 1, on the initiative of V.I. Lenin, the Ukrainian Revolutionary Military Council was created under the chairmanship of I.V. order to attack Kiev. By this time, in the neutral zone, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army was formed from separate units and partisan detachments, consisting of two divisions. Fulfilling the instructions of Lenin and Stalin, despite the opposition of the Trotskyist traitors, this army quickly went on the offensive. The First Ukrainian the division from the Unechi region advanced on Kiev, headed by the Bogunsky regiment of Shchors, led by the Tarashchansky regiment of Bozhenko, who was subordinate to Shchors as a brigade commander.

How. As soon as Shchors went on the offensive, volunteers again reached out to him from all sides. Almost every village fielded a platoon or company of rebels who had been waiting for Shchors for a long time. Shchors reported: “The population everywhere welcomes joyfully. Great influx of volunteers vouched for by the Councils and Committees of the Poor.”

As far as Klintsy, where the 106th German regiment was concentrated for evacuation, the Bogunians passed without a fight. In Klintsy, a trap was being prepared for Shchors. The German command openly announced the evacuation of troops, and armed the urban bourgeoisie and the Haidamaks. Shchors moved the regiment into the city, counting on the neutrality of the Germans, but when the first and third battalions of the Bogunians set foot in Klintsy, the Germans, calmly letting them through, suddenly hit in the rear. Shchors quickly turned his battalions against the Germans and cleared his way back with a swift blow. Bogunsky regiment - withdrew to their original positions. The cunning of the German command forced Shchors to change tactics. He ordered the first battalion of the Tarashansky regiment, which had already occupied Ogarodub, to immediately turn to the Svyatets junction and, having gone to the rear of the Germans, to cross the Klintsy-Novozybkov railway. Maneuver

Shchorsa - turned out to be successful - Now the Germans were trapped. The Klintsrva garrison of the invaders was surrounded. The German soldiers refused to obey their officers and laid down their arms. Thus ended the attempt by the invaders to delay the advance of Shchors. German-; the command was forced to negotiate about. evacuation. The meeting took place in the village of Turosna, the Germans undertook to clear Klintsy on December 11 and, on the way, to leave the bridges, telephone and telegraph in complete safety. A hasty evacuation began in Klintsy. tion. The Germans, selling weapons, left Ukraine, the Gaidamaks, having lost the support of the occupiers, fled the city. Shchors telegraphed to the division headquarters: “Klintsy is occupied by revolutionary troops at 10 o’clock in the morning. The workers met the troops with banners, bread and salt, with shouts of "Hurrah".

From Klintsy, the Germans retreated along the railway to Novozybkov-Gomel. Every day the retreat of the invaders became more hasty and disorderly. - the western part of the territory of the Bryansk Territory The threat to Bryansk has passed.

In Unecha, Novozybkovo, Zlynka, the buildings where the headquarters of the units of the Bogunsky regiment were located have been preserved to this day; and in Klintsy a house was preserved, where there was a coffin with the body of the legendary commander N. A. Shchors, who was killed near Korosten. There is a memorial plaque on the house. In Klintsy and Novozybkov, the working people erected monuments to N. A. Shchors.

The name of Nikolai Aleksandrovich Shchors, a hero of the Civil War, a talented commander of the Red Army, is dear and close to the workers of our region. In the Bryansk region, he began his activities as an organizer and commander of the first detachments of the Red Army.

N. A. Shchors was born in the village of Snovsk (now the city of Shchors) in the Chernigov province in the family of a railway engineer. He received his primary education at the Snovskaya railway school. In 1910 he entered the military paramedic school in Kyiv. The end of school coincided with the beginning of the First World War. Shchors serves as a military paramedic, and after graduating from the ensign school in 1915, as a junior officer on the Austrian front. In the autumn of 1917, after being discharged from the hospital, Shchors arrived in his native Snovsk, where he contacted an underground Bolshevik organization, and in March 1918, Shchors went to the village of Semyonovna to form an insurgent Red Guard detachment.

In February 1918, the governments of Germany and Austria-Hungary began the occupation of Ukraine. German troops occupied the western districts of our region. Of great importance in organizing a rebuff to the German invaders was the arrival of N. A. Shchors with a detachment to the Bryansk region.

In September 1918, N. A. Shchors, on behalf of the Central Ukrainian Military Revolutionary Committee, formed the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Regiment named after Bohun, a brave associate of B. Khmelnitsky, from separate rebel detachments in the Unecha region. Party organizations of the Bryansk region actively participated in the formation of the regiment. The workers of Starodub, Klintsov, Novozybkov, and Klimov went to N. Shchors. In October, the Bogunsky regiment already numbered over one and a half thousand bayonets.

In November 1918, a revolution broke out in Germany. The Bogunians fraternize with the soldiers of the German garrisons in the border zone near the village. Lyshchichi and send a telegram to V. I. Lenin. A response telegram from the leader arrives in Unecha: "Thank you for the greeting... I am especially touched by the greeting of the revolutionary soldiers of Germany." Further indicating what measures should be taken for the immediate liberation of Ukraine, V. I. Lenin writes: “Time does not endure, not an hour can be lost ...”

At the end of November 1918, the Bogunsky and Tarashchansky regiments went on the offensive. On December 13, the Bogunians liberated the city of Klintsy, on the 25th Novozybkov, having occupied Zlynka, began an attack on Chernigov. On February 5, 1919, the Bogunsky regiment entered Kyiv. Here the regiment was awarded an honorary revolutionary banner, and commander Shchors was awarded an honorary golden weapon "For skillful leadership and maintenance of revolutionary discipline."

In early March, by order of the Revolutionary Military Council, N.A. Shchors was appointed commander of the 1st Ukrainian Soviet Division, which successfully operated against the Petliurists and Belottolyaks near Zhytomyr and Vinnitsa, Berdichev and Shepetovka, Rivne and Dubpo, Proskurov and Korosten.

By the summer of 1919, Denikin became the main opponent for the Soviet Republic, but the Shchors division remained in the West, where, in accordance with the plan of the Entente, the Petliurists began to attack. I. N. Dubova, former deputy commander of the Shchors division, writes about this difficult time: “It was near Korosten. Then it was the only Soviet foothold in Ukraine, where the Red Banner victoriously fluttered. We were surrounded by enemies. On the one hand, the Galician, Petliura troops, on the other, Denikin’s troops, and on the third, the White Poles squeezed tighter and tighter the ring around the division, which by this time had received the numbering of the 44th. In these difficult conditions, both on the offensive and on the defensive, Shchors showed himself to be a master of a wide, bold maneuver. He successfully combined the combat operations of regular troops with the actions of partisan detachments.

August 30 in the battle near Korosten II. A. Shchors was killed Nachdiv was 24 years old. The Bolsheviks of the division decided to take the body of Shchors to the rear, to Samara (now the city of Kuibyshev), where he was buried. Nikolai Alexandrovich Shchors enjoyed great prestige among the troops and among the population. Having joined the ranks of the Bolshevik Party in 1918, he wholeheartedly served the party and the revolution until the end of his life.

The death of N. A. Shchors echoed with deep sorrow in the hearts of the working people of the Bryansk region. The inhabitants of Klintsy wished to say goodbye to the ashes of their beloved hero-commander. The coffin with the body of Nikolai Alexandrovich was brought to Klintsy and installed in the house of the county party committee.

People's memory carefully preserves the image of a talented commander. In the cities of Shchors, Kyiv, Korosten, Zhitomir, Klintsy, Unecha, monuments were erected on the grave in Kuibyshev. In places associated with the stay of N. Shchors in the Bryansk region, memorial plaques were installed.