Death of Charles 12th King of Sweden. Charles XII and his retreat to Bendery

The decisive role in achieving victory at Narva in 1700 undoubtedly belonged to King Charles XII. He carried out the unexpected arrival of the Swedish army near Narva for the Russians. He is the main organizer of the battle. With his immense thirst for battle and courage, and personal example, he inspired his warriors. They believed in him and worshiped him. It has long been known: courage is the beginning of victory. In the battle near Narva, the 18-year-old Swedish king showed off his talent as a commander, extraordinary military success and happiness, he covered Swedish weapons with glory.

In 1700, Denmark, Poland and Russia began the Northern War against Sweden. The 28-year-old Russian Tsar Peter I led a 32,000-strong army to Narva and besieged the city.

The Swedish throne was then occupied by the 18-year-old King Charles XII - an extraordinary and far from ambiguous personality. He was born on June 17, 1682. His father Charles XI left his son a first-rate European kingdom with a strong economy, an excellent system of government, a strong army and navy, and extensive overseas possessions outside the metropolitan area. He died in 1697, when his son was 15 years old.

Having become king, Charles XII got rid of guardianship after 7 months and became a sovereign monarch. The young king was a warrior by vocation; already at the age of 7 he dreamed of military campaigns, envied the glory of Alexander the Great and persistently prepared himself for this field. He despised luxury, walked without a wig, in a simple blue uniform, observed a soldier's regimen, developed extraordinary strength in himself through gymnastics, paid special attention to the art of war, the possession of all types of weapons, loved hunting bears and other animals, was hot-tempered and quick-tempered, inflamed like powder.

He was not afraid of the triple alliance of states and the upcoming war. On April 13, 1700, the king left Stockholm, announcing to his relatives that he was going to have fun at Kungser Castle, and he himself, with a 5,000-strong army on ships, rushed to the Danish shores. He took Denmark by surprise, and under the threat of the destruction of Copenhagen, the Danish king Frederick IV was forced to make peace. Denmark left the war.

Having dealt with one enemy, the king rushed to besieged Riga. The Polish king Augustus II, fearing the approaching Swedes, lifted the siege of the city on September 15 and retreated without a fight.

Now the Swedes were waiting for Narva, besieged by Russian troops. On September 20, 1700, a Swedish flotilla consisting of 9 ships and two frigates raised sails in Karlskrona and moved to the shores of Estonia. On September 25, the squadron arrived at the port of Pernov (now Pärnu). Approaching the shore on the yacht "Sofia", the king was so inflamed with the desire to reach it quickly that he lost caution and almost drowned. The brave General Renschild saved him.

The young king's thirst for battle and self-confidence knew no bounds.

Do you really think that 8,000 brave Swedes cannot cope with 80,000 Moscow men? - he declared to his entourage.

On November 19, 1700, by noon, the Swedes deployed their battle formations in front of the positions of the Russians besieging Narva. Before the battle, in full view of his army, Charles XII dismounted from his horse, knelt down, said a prayer for victory, hugged the generals and soldiers standing nearby, kissed them, and mounted his horse. Exactly at 2 o'clock shouting:

God is with us! - The Swedes rushed to attack.

The balance of forces was as follows: Russians - 32,000, Swedes - 8,000. At the very beginning of the battle, the center of the Russians was crushed, their disorderly retreat and flight began. On the left flank, Weide's division, retreating, began to push Sheremetev's mounted militia towards the waterfalls. The stormy Narova and its waterfalls swallowed up more than 1,000 riders and horses. On the right flank, Golovin's division, retreating in panic, rushed to the floating bridge. It couldn't bear the load and burst. And here the waves of the Narova swallowed up their victims en masse. To this the king remarked contemptuously:

There is no pleasure in fighting the Russians, because they do not resist like others, but run.

Only the Preobrazhensky, Semenovsky and Lefortov regiments and the gunners-artillerymen steadfastly repelled the attacks of the Swedes. The king was undaunted; combat was his element. There, in the thick of the battle, he himself led his soldiers to attack several times. During the battle, the king fell into a swamp, got stuck with his horse in a quagmire, lost his boot and sword, and was rescued by his retinue. The bullet hit him in the tie. A cannonball killed a horse underneath him. Surprised by the steadfastness of the three Russian regiments, the king exclaimed:

What men are like!

The losses of the young, insufficiently trained, unfired Russian army in battles were enormous: 6,000 killed, 151 banners, 145 guns, 24,000 guns, the treasury and the entire convoy. Many foreign generals and officers, led by the commander Duke de Croix, surrendered to Charles XII. The Swedes lost 1,200 people.

Victory, as you know, is always attributed to the talent of the commander and the courage of the soldiers, and defeat is explained by a fatal accident. The decisive role in achieving victory at Narva in 1700 undoubtedly belonged to King Charles XII. He carried out the unexpected arrival of the Swedish army near Narva for the Russians. He is the main organizer of the battle. With his immense thirst for battle and courage, and personal example, he inspired his warriors. They believed in him and worshiped him. It has long been known: courage is the beginning of victory. In the battle near Narva, the 18-year-old Swedish king showed off his talent as a commander, extraordinary military success and happiness, he covered Swedish weapons with glory.

On November 22, 1700, accompanied by a brilliant retinue, Charles XII and his troops solemnly entered Narva. A thanksgiving prayer service was held in the church. The celebration of the winners was accompanied by the firing of cannons and rifles. Rudolf Horn, who led the defense of Narva Genting, was promoted to general. In honor of the victory, 14 medals were knocked out, incl. two are satirical. One of them depicts a crying Tsar Peter I running from Narva, his hat falls from his head, his sword is thrown away, the inscription: “He went out and cried bitterly.”

The victory turned the head of the young victorious king; he believed in God’s providence. He had a map of Russia hanging in his bedroom, and he showed his generals the road to Moscow, hoping to quickly and easily reach the heart of Russia. General Stenbock:

The king thinks about nothing more than war, he no longer listens to advice; he looks as if God were directly instilling in him what he should do.

Charles XII mistakenly considered Russia to be out of the war and refused a profitable peace with it.

In 1701, Charles XII decided which of the unkilled enemies to deal with, since victory in battle is not yet victory in the war. The choice fell on the king of Poland, the Saxon elector Augustus P. Having won several victories in battles, he managed to oust Augustus II from Poland, deprive him of the royal crown, and impose on the Poles a new king, Stanislav Leszczynski, who had previously been the Poznan voivode. Poland then became an ally of Sweden. All this took several years.

At this time, having recovered from the Narva defeat, the Russian army began to win victory after victory on the shores of the Baltic Sea (Erestfer near Dorpat, Noteburg, Nyenschanz, Dorpat, Narva, etc.). Despite this, Charles XII's self-confidence continued to remain boundless. Having received news of construction. Peter I of St. Petersburg, the king grinned:

Let him build. It will still be ours.

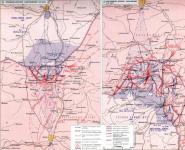

After a series of victories in Poland and Saxony, the rested army of Charles XII invaded Russian territory in the spring of 1708. He intended to defeat the Russian army in one battle, capture Moscow and force Peter I to conclude a profitable peace. But the Russian army did not follow the royal will. Avoiding a general battle, it retreated to the east, with the goal of “tormenting the enemy” with attacks by small detachments and the destruction of provisions and forage.

Failures began to follow one after another. Great hopes for the Ukrainian Hetman Mazepa were not justified. Levenhaupt's 16,000-strong corps, coming from the Baltic states to replenish the army of Charles XII, was defeated on September 28, 1708 near the village of Lesnoye, while the Russians got all 8 thousand carts with food, gunpowder, cannons and fodder. An unkind but prophetic rumor spread throughout the army: “Karl is looking for death because he sees a bad end.”

“The invincible Swedes soon showed their backbone,” wrote Peter I from the battlefield. At the battle site, the Swedes left 9 thousand corpses, 20 thousand surrendered. The day before, Charles XII, wounded in the leg, together with Mazepa, accompanied by a small detachment, barely escaped captivity by taking refuge in Turkish possessions.

For another 6 years, pride did not allow the unfinished king to return to his fatherland. He unsuccessfully tried to end Russia with the wrong hands, dreaming of entering Moscow at the head of the Turkish cavalry. However, the Turkish Sultan Ahmed III was content with the return of Azov, and on July 12, 1711, the Russian-Turkish war ended with the signing of peace.

The Sultan was tired of the whims, claims and ambitions of the parasite king, and he ordered the “iron head” to be sent home. But the king of Sweden was not used to carrying out other people's orders. Then the Sultan sent the Janissaries. The king with a handful of his bodyguards fought off an entire army. The Janissaries set fire to the house. From the burning house, Charles XII decided to break into the neighboring house. With a pistol in one hand and a sword in the other, on his way out he caught his spurs on the threshold and fell. Then the Janissaries captured him.

Finally, in 1715, the warlike wandering king returned to Sweden. He once dreamed of returning with the triumph of a great commander and winner. Then he had reason to say:

God, my sword and the love of the people are my allies.

However, in the end, past victories and sacrifices were fruitless. After a 15-year absence, the country met its king devastated, depopulated, without an army, navy or allies, having lost all its overseas possessions. The plight was aggravated by crop failure and plague. It was necessary to increase taxes and issue copper money - “coins of need”.

The king saw a way out of this situation in the creation of a new army and new wars. But by that time, Sweden was no longer the same as before, and the king was not the same. On November 30, 1718, Charles XII was killed during the siege of the Norwegian fortress Frederikhall. Where the bullet that killed the king came from, whose it was - either Norwegian or Swedish - is still unclear.

Charles XII was 15 when he was crowned the sole ruler of great-power Sweden.

The war was his life and became his death.

While still a teenager, the king, sword drawn, led his Carolinians into battle, winning one victory after another.

Military luck betrayed him on a June day in 1709 near Poltava, where Russian Tsar Peter I defeated the Swedish army.

Charles XII died in 1718 from a bullet during the siege of the Fredriksten fortress, and with his death the era of Swedish great power ended.

The heroic young King Charles is black with smoke and gunpowder, and the roof of his majestic Royal House is on fire.

The shot almost took his life, blood runs from a wound on his nose and cheek. The left hand, where the saber hit, is also bleeding.

The king impales several enemies on his long sword, and kills others with pistol shots.

With a sword in his bloody hand and a pistol in the other, he runs out of the set fire to the house. He trips over his own spurs and falls to the ground. The Turks rush against Charles XII, they were promised a good reward if they take the king alive.

Bendery kalabalyk is finished.

The proud army of the Royal Carolinians until recently inspired fear throughout the world.

Now the king lies on the ground, and the enemy's boots have pressed his head into the mud.

There are only a few drabants left. 12 were seriously wounded, 15 died in the battle.

The dramatic events in Bendery are an important part of Swedish history. But more on that later.

Good signs, harbingers of good luck and success

June 17, 1682, quarter to seven in the morning. The sun shines through the windows of Tre Krunur Castle in Stockholm. The royal residence is a fortress built by Earl Birger four centuries earlier.

The troubled man in the office is called "Grey Cape". This is the 27-year-old Swedish king Charles XI.

He got his nickname because he used to dress in gray and sit unrecognized in the back pews of churches and courts.

The Gray Cloak is the nightmare of the Swedish nobility. If he sees a judge, governor, or church minister neglecting his duties, the culprit will face resignation, investigation, and punishment.

He is popular, truly loved by peasants and lower class citizens who have suffered centuries of oppression at the hands of aristocrats and officials.

The king shudders from the roar of a cannon shot among the stone walls. The first is followed by new volleys, a salute of twenty-one shots from the palace tower and then twenty-one more without any delay.

The number of volleys is important, it means that Queen Ulrika Eleonora has given birth to a prince - the heir to the throne.

The constellation Leo and its brightest star, Regulus, the lion's heart, twinkle in the early summer sky. The royal astrologer says this is a good sign.

Karl was born wearing a shirt, that is, with a piece of the amniotic sac sitting on the top of his head, like a cap.

This is a very special sign: such a child is destined for great luck and success in life.

Like any mother, Ulrika Eleonora believes that her son is handsome. He inherited her high forehead, full lips, and prominent chin. He has a big nose.

From his father, the prince received clear blue eyes and a name. 15 years later he would be crowned King Charles XII.

He is only six when he is taken from his mother, the queen, and placed on a separate floor of the castle. The prince has his own teachers. He is being raised as the future autocrat of great Sweden.

Prince Charles is training to fight

The father draws up a schedule of classes: Prince Charles must learn to read and count, cram laws and government regulations and, most importantly, learn piety.

Strict professor Anders Nordenhielm opens the world of books to the prince and explains how to behave at court, how to speak with peasants in their dialect, and with learned men in Latin.

The purpose of intensive training is to gain experience and courage to make decisions without asking the opinions of others.

Little Karl is interested in mathematics. He studies several languages, learning Danish from his mother. German and Latin were also important at that time, and Karl was a capable student. He crams French reluctantly. Young Charles considers the French he meets at court to be rude and arrogant. The prince's favorite lesson is with officer Carl Magnus Stuart, an expert in fortification.

The prince likes to look at drawings depicting battles in which his grandfather and father participated. Will the cavalry attack from the western flank? Wouldn't it be better to place the cannons on a hill and shoot from top to bottom? Was the infantry positioned correctly?

Prince Charles is training to fight.

The Baltic is almost an inland sea of Sweden

Grandfather Charles X was a soldier king. His most famous war was with his arch-enemy Denmark, during which he walked across the ice from Jutland to Copenhagen.

The war ended with the Peace of Roskilde, Denmark ceded Skåne, Blekinge, Bohuslän, Bornholm and Trøndelag to Sweden.

Father Charles XI was also a war hero. With the help of cavalry, he defeated the Danish king Christian V at the Battle of Lund on December 4, 1676. This was one of the largest battles in the history of Scandinavia. In eight hours, six thousand Danes and three thousand Swedes died, blood flooded the battlefield.

Young Karl also wants to become a hero.

In June 1689 he is seven years old and has recently learned to write. His notebook has been preserved:

“I would like one day to have the happiness of following my father’s example on the battlefield.”

When Karl is 11, his 36-year-old mother Ulrika Eleonora dies. The 41-year-old father passed away four years later, on April 5, 1697, after a serious illness. He is sure that he was poisoned (but the autopsy shows stomach cancer).

No Swedish king has ever inherited such a powerful state.

The population of great Sweden is 2.5 million people. The Baltic Sea is practically a Swedish inland sea.

Charles is 15. His father's will states that the country will be ruled by a regency government until Charles reaches adulthood.

Three days after the funeral, the young man dissolves the Riksdag and becomes the sole ruler of Sweden.

He is a cocky young man. During the coronation in the Church of St. Nicholas, the king himself places the crown on his head. As a ruler, by the grace of God, he does not take a royal oath, but allows the bishop to perform the ritual of anointing for the kingdom.

The nobles pursued their own interests when they tried to recognize the king as an adult as early as possible (at that time, the age of majority was usually considered to be 18 years old).

Noble families lost both dignity and possessions when Charles XI carried out the so-called reduction and nationalized the lands of the crown.

Now the aristocracy seized the opportunity to regain their wealth and privileges.

The boy king is easy to manipulate. How wrong they were.

The clergy, one of the four Swedish estates at the time, protested. The priest Jacob Boëthius of Mura wrote a letter to the nobility of Stockholm, in which he objected to absolutism as a form of government.

The fifteen-year-old king is furious. Six horsemen went to Dalarna, captured the priest in the middle of the night and brought him to Stockholm. He was sentenced to death for treason and, awaiting execution, was placed in the Nöteborg fortress (Oreshek - approx. per.) on Ladoga. Twelve years later the priest was granted pardon.

He's not interested in women

Karl was raised as a real man. At the age of four, he sat on his own horse in front of his father the king and received his first military parade of guards on the Jerdet field in Stockholm.

Karl loves hunting. At that time, Stockholm was surrounded by wild lands. At the age of eight, he shot a wolf for the first time on Lidingö. The first bear is at eleven on the island of Djurgården.

Not much time passes, and Karl begins to think that hunting a bear with a gun is too boring. He arms himself with a club or a wooden pitchfork, which is much more exciting, although deadly. Karl kills or catches many bears this way.

At 13, Karl falls ill with a common disease - smallpox. The disease is benign, and soon the prince is healthy again.

He loves horse riding. One day in May, twelve-year-old Karl and his father Karl XI travel to Stockholm from Södertälje in just two and a half hours. They travel the entire way at the fastest gallop.

Context

Ambassador of Sweden to the Russian Federation: Poltava directed us in a peaceful direction

BBC Russian Service 06/29/2009The myth of Poltava after 1709

Mirror of the Week 11/30/2008Ivan Mazepa and Peter I: towards the restoration of knowledge about the Ukrainian hetman and his entourage

Day 11/28/2008How Peter I ruled

Die Welt 08/05/2013 When Charles becomes king, he is still a pimply teenager. 176 centimeters, boots, narrow hips, broad shoulders. Blue eyes, brown hair under a baroque wig. He is proud of the marks that smallpox left on his cheeks - they make his face look more mature.Power inherited by Charles XII

The Swedish state included Finland and Karelia. In the Baltic states, Sweden controlled the provinces of Livonia, Estonia and Ingria. We owned a large part of Norway. In northern Germany, Sweden controlled Bremen and Ferden, part of Pomerania, as well as the city of Wismar.

Charles XII dreamed of annexing new lands and closing the country around the Baltic Sea, but the defeat of the Carolinian army near Ukrainian Poltava on June 28, 1709 made the dream unrealizable.

The young unmarried ruler of the powerful Swedish state is an interesting match for many royal houses in Europe. But he is not interested in women.

Princes and kings send him portraits of their daughters offering their hand in marriage. The princess from the royal house of Württemberg, as well as the daughter of Prince von Hohenzollern, personally pay a visit to Stockholm, but their attempts to charm the king are unsuccessful.

Politely but adamantly, Charles XII rejects all candidates. Later, he does not communicate with the prostitutes who always accompany the Carolinians on their hikes.

Some historians believe that the king was homosexual, but there is no evidence for this.

Running a country takes time. The aristocrats who thought they could control the fifteen-year-old king are deeply disappointed. Charles XII drives away almost all the intriguers; the only one he trusts is 50-year-old Secretary of State Carl Piper.

“This is my will, and so be it,” says Charles XII if his advisers object to his decisions.

The Bible is the young king's law. When the relationship between married guardsman Johan Schröder and a comrade's wife is discovered, the guardsman is put on trial. Advisors propose to punish him with prison, because such a sin is not punished more severely in any Christian country. The king wants the Lord to show his punishment himself, and proposes to shoot the guardsman. Let it be so.

A month after the death of Charles XI, a fire occurs in Tre Krunur Castle. Karl, who is now an orphan, moves with his court first to Karlberg (now the military academy), and then to the Wrangel Palace on Riddarholmen (now the Court of Appeal). There he organizes wild celebrations.

The real madness begins when the king's second cousin and future son-in-law, Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp, arrives in the summer of 1698 to woo the king's beloved sister, Hedwig Sophia.

We know about what happened within the castle walls from the diary of the royal page Leonard Kagg.

One day, Friedrich and Karl release wild hares in the galleries of Karlberg and compete to see who can shoot the most. Another time, on August 9, 1699, according to the diary, they dined at the same table with a tame bear. The bear eats a sugar pyramid, drinks a jug of wine, and falls out of a third-story window. There was a case when the servants were ordered to deliver calves and goats after dinner. Charles XII and Frederick compete in cutting off heads with one blow. Blood splatters on carpets and furniture.

Foreign diplomats write to their capitals about a young savage who seems to have lost his mind.

On the throne is a young and inexperienced reveler

There are enemies both nearby and in the distance, for example, two cousins of Charles XII. One is called Augustus, he is the king of Poland and the elector of Saxony. The second is Frederick IV, King of Denmark.

The third is Russian Tsar Peter, a power-hungry 28-year-old ruler who intends to make his underdeveloped kingdom a superpower.

Sweden's ambitions irritate neighboring countries. Since the time of Eric XIV in the 16th century, we have captured more and more new territories.

Russia lost Ingria and Kexholm. The Germans lost Vorpommern, parts of Western Pomerania, Wismar, Stettin, Bremen and Verden, as well as the important islands of Rügen, Usedom and Wollin. Poland ceded Livonia to us.

Sweden is the second largest country in Europe, only Russia is larger.

The king wants to make the Baltic Sea inland. There is also a security reason for this: the state needs a buffer zone.

On our throne is a young, inexperienced king, whom diplomats call a reveler.

The king's most dangerous enemy

Russian Tsar Peter I (1672-1725) was 28 years old when he began the war against Charles XII. The first battle - the Battle of Narva - ended in a shameful defeat for the king.

The next major clash between Swedish and Russian forces was the battle of Poltava. Charles XII lost, and luck turned away from the Swedish power.

And Peter the Great built St. Petersburg on land conquered from Sweden.

Many Swedish prisoners of war worked on the construction in slave-like conditions, and many of them died in the swamps near the Neva River, where the Tsar founded his new city.

Neighbors want revenge

There is a chance to split Sweden, and the enemies are secretly plotting.

A conspiracy between the king's cousins and Tsar Peter leads to what the history books call the Northern War.

Augustus, nicknamed the Strong, becomes king of Poland in the same year that Charles XII comes to power. 28-year-old Augustus dreams of defeating the Swedes, annexing new lands and laying the foundations of a strong monarchy.

Augustus is known for his political cunning, he is a real intriguer. Augustus willingly demonstrates his physical strength at feasts, for example, straightening horseshoes with his bare hands.

Women are his passion. According to some sources, he recognized the paternity of 354 children. In his marriage to Christiane Eberhardina of Brandenburg, he has only one child - the son Friedrich August, the future Elector of Saxony.

29-year-old Frederick IV is more interested in glitz and luxury than in boring government affairs. He devoted most of his 31-year reign to pleasures, holidays and love affairs.

But Frederick also has a dream - to return the provinces that his father lost under the terms of the Roskilde Peace.

Tsar Peter is a real giant with a height of 203 centimeters. He is 10 years older than Charles XII, and his main desire is to defeat the Swedes, open his way to the shores of the Baltic Sea and make Russia a great European power.

Thank Charles XII for his tax return

The king believed that the current taxation system was unfair. Many, including the nobility and townspeople, did not pay income tax according to their income. In 1712, Charles XII introduced universal taxation. A certain percentage of the income had to be allocated to taxes, which the king needed to strengthen the army. The Swedes protested loudly, so the system was abolished after the death of the king. However, in 1902 the declarations were returned.

Signal: the fatherland is in danger

In the late winter of 1700, Charles XII travels to Kungsor to hunt bears. On March 6, a mortally tired messenger Johan Brask from the Nyland infantry regiment appears. He gallops through the snow, carrying ominous news.

The Bothnian Sea froze, and a messenger rode from Finland and northern Sweden for four weeks to convey an important message.

The troops of Augustus the Strong have stormed Kobronšantz in Swedish Livonia and are now advancing towards Riga.

At the same time, the Danes occupied the Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp.

Sweden was attacked from two sides. A third front will soon arise, but no one knows about it yet. Tsar Peter marches to Ingria.

Sweden is ready for war. Throughout the country, church bells ring during the day, this is a signal: the fatherland is in danger.

We have a peasant army of 18 thousand infantry and eight thousand cavalry - the so-called Indelta soldiers, who received military surnames that have survived to this day - Mudig ("brave" - approx. transl.), Hord ("severe" - approx. trans.), Rask (“fast,” — trans.), Flink (“agile,” — trans.), Tupper (“brave,” — trans.).

They stop working in the fields and forests, put on their soldier's uniform and go to the rally areas where they meet with their corporals. Before they were studying, now everything is serious. The fleet has 15 thousand people and 38 battleships. In addition, there are recruiting troops in the life regiment and in garrisons.

In total, Sweden has 70 thousand people - 12 cavalry regiments and 22 infantry regiments to defend the king and the fatherland. It was the turn of the Carolineers.

In the early morning of April 14, 1700, Charles XII mounts his horse Brandklipparen, kisses his grandmother, Queen Dowager Hedwig Eleonora, on the cheek and gallops south. Karl's four dogs are running nearby - Caesar, Pompe, Turk and Snuskhane. None will survive wars.

The 17-year-old king is the commander-in-chief of the greatest and best army in Swedish history.

Charles XII would never see his capital again. He will return to Stockholm only in a coffin, after 18 years of battle.

The king had been preparing for this morning for a long time

First you need to deal with the rebellious cousin Frederick. He sent 20 thousand people to capture the fortresses of Holstein.

King Charles arrives in Karlskrona, a new city founded by his father with the aim of creating a base for the Swedish fleet south of Stockholm.

A storm is raging when Karl, with four infantry battalions of about three thousand people, crosses the strait on the evening of July 25, 1700 (Oresund - approx. transl.). The king and his soldiers board boats and row towards the shore near Humlebeek while the warships pour fire on the defenders on the shore.

The attack begins at dawn. Charles XII leads the troops. This is a real battle, he has been practicing and preparing for this morning for a long time.

Bullets whistle, cannonballs scatter sand and earth, tear apart the bodies of enemies.

“Let this be my music from now on,” declares the king.

The first battle of Charles XII does not last long. The Danes have given in and they are fleeing. They are pursued by the Carolineers. They are about to take Copenhagen and the king surrenders. Charles XII won his first victory on the battlefield.

Denmark is broken, but not broken, it remains a threat until the end of the life of Charles XII.

Narva - triumph of Charles XII

Now let's teach the second cousin a lesson. The Swedish provinces in the Baltic are under threat. As Karl boards the warship Västmanland in Karlhamn, a messenger arrives with new news: Tsar Peter wants to capture Narva, the most important Swedish city in Estonia near the Russian border.

Charles XII changes plans, Narva is more important than the campaign against Augustus. We need to save the strategic fortress.

Caroliners walk several miles a day in the Estonian rains. It is difficult for horses to pull cannons through clayey mud. The soldiers are hungry. Their bread is moldy.

On the morning of November 20, 1700, the king stands on a hill and examines the besieged city through a telescope.

There are 30 thousand Russians there.

The king is adamant.

“In battle we win by the will of the Lord, and he is with us.”

At half past two in the afternoon the king kneels before his men. He is wearing a simple soldier's blue and yellow uniform without insignia, rough boots with high tops and a black cocked hat. He has a long sword at his side.

Together with the Carolinians, the king sings a psalm they have learned:

“The Lord, who created heaven and earth, will help us and comfort us.”

At this moment something happens that will give the Swedes a huge advantage. It begins to snow heavily. The western wind and blizzard hit the faces of the Russians; they do not see what is happening on the opposite side of the battlefield.

The king is 18 years old, and this is his baptism of fire.

The Swedes are on the offensive. There are no drums or trumpets, in complete silence the Carolinians walk through the snowstorm, raising their pikes and muskets. In the vanguard are grenadiers with hand grenades - explosive shells with a fuse that are thrown at the enemy in close combat.

The Russians notice the Carolineers when they are only 30 meters away. The Swedish troops rush forward with all their might, swords drawn.

The blood of the dead and wounded mixes with the icy porridge. The Russian army was cut in two and sandwiched between defensive structures and the icy waters of the Narva River.

The Russians panic and flee. Many try to cross the river on a wooden bridge, it breaks, thousands of Russians drown. From the shore, caroliners shoot swimming enemies.

The Russians capitulate, and all the tsarist commanders are captured.

In the battle, 700 Carolinians were killed and 1,200 were wounded. Russian troops lost approximately 10 thousand people.

This is the greatest victory of Charles XII. He later finds a bullet in his scarf, lodged a few millimeters from the carotid artery.

For Peter the Great, this defeat is a serious setback. For the next nine years, he will prepare to take revenge.

Three big victories in one year

On June 17, 1701, when the king was celebrating his 19th birthday, the Carolinians launched an attack on Augustus the Strong. Reinforcements arrived from Sweden to replace those who had fallen in battle or died from disease.

The forces meet on the Western Dvina River, near Riga in what is now Latvia.

The commander of the strategic Swedish fortress in Riga, Count Erik Dahlbergh, waited a long time for the king with reinforcements. He held the defense masterfully. He ordered holes to be made in the ice of the river to prevent the enemy from crossing it. When the enemy began the assault, Dahlberg's drabants poured boiling tar on him.

Augustus' troops grouped on the southern bank of the river, and 10 thousand Carolinians came from the north.

The attack begins at dawn on July 9. The Carolinians set fire to raw hay and manure and, under the cover of smoke, transport six thousand infantry and a thousand cavalrymen to the other side. The cannons in the blockhouses terrified the Poles and Saxons.

The battle lasts only a few hours, then the enemy flees.

Another triumph for Charles XII. He has already won three major victories in one year.

In Stockholm, commemorative medals are issued in which the Swedish king is depicted with three defeated monarchs at his feet.

But Cousin Augustus is not defeated. Charles XII and the Carolinians fight in Poland and Saxony for five long and difficult years, and it takes many bloody battles to force Augustus to make peace. The Treaty of Altranstedt was signed in 1706.

Scorched earth tactics

To Moscow. The Tsar must be defeated and forced to capitulate. Charles XII is confident of victory. God is on his side.

In the autumn of 1707, the king leads an army of 44 thousand, they pass the lands that now belong to Belarus.

For the first time, they manage to measure their strength with the tsar in the city of Golovchin, not far from present-day Minsk in Belarus. The Russian army is four times larger than the Swedish one, but the Carolinians destroy it.

“This is my most glorious victory,” declares the king, according to the diary of army chaplain Andreas Westman.

Tsar Peter is furious. Defeat haunts him. He removes his generals from their posts, and orders soldiers wounded in the back to be shot on suspicion of fleeing the battlefield.

The path to Moscow leads along an endless plain. Tsar Peter used scorched earth tactics. His soldiers are burning Belarusian villages, slaughtering livestock, and putting the population to flight.

Carolinians have nowhere to buy or steal. Their food supplies are running low.

Tatarsk is located 40 miles east of Moscow. There comes a turning point in the war. There are only adversities ahead.

September 10, another battle. 2,400 Carolinians against four times the Russian forces. Charles XII is at the head of the army, as always. His horse falls dead from a bullet.

But this does not decide the outcome of the battle. The Russians are retreating. This is the king's new tactics. His soldiers carry out quick surprise attacks and disappear just as quickly, this is the tactics of guerrilla warfare.

The goal is to inflict as much damage on the Swedes as possible without risking your own life.

As the Russians retreat, they set fire to villages and towns.

“Everything is on fire, everything is like hell,” writes 26-year-old dragoon Joachim Lyth in his diary.

A crisis is coming. The path forward is blocked. Charles XII, with his starving army, decides to turn and head south to Ukraine, and from there go to Moscow by a different route.

We have to go quickly. There is a danger that the king will be the first to do so and will again burn out all the villages and fields.

But Tsar Peter has a powerful “ally” - the Russian winter.

Charles XII is the first to be defeated due to frost.

Napoleon will be next in a hundred years. His march on Moscow in 1812 would be a disaster that would cost him dearly. And in World War II, Adolf Hitler's offensive against the Kremlin would fail for the same reason.

Russian winter, the worst winter of the century

December 1708, the worst winter of the century. Deadly winds sweep across Ukrainian fields.

Caroliners slowly freeze to death while sitting astride horses or on carriage trains. The worst situation is for the infantry. They have shoes with birch bark soles, and they simply cannot walk when their toes turn to ice.

Three thousand people die, and even more become crippled after field surgeons amputate frostbitten body parts without any pain relief.

Spring is coming. The war has been going on for nine years. Charles XII is 26. Only 25 thousand people remain from the Carolinian army. The troops were stationed in several villages near Poltava.

Poltava: Carolineers are marching towards death

In the spring of 1709, anxiety grew in Stockholm. Several months have passed, and there is no news from Charles and his victorious army. Mail doesn't work well. The enemy stops and captures the mounted Swedish messengers. Letters that do arrive often turn out to be six months old.

Poltava is located on the Vorskla River in Ukraine. There is a Russian garrison there, rich in food and ammunition.

Behind the protective rampart are 4,200 Russian soldiers, easy prey, according to Charles XII.

What mistake. Disaster strikes. The era of great power in Sweden is coming to an end.

Everything goes wrong from the very beginning. On June 17, the king celebrates his 27th birthday. In the morning, he, along with several officers, leaves the base camp on horseback to reconnoiter the location of the enemy camps.

They meet Russians at the river. They fire several shots from muskets. The king is sitting on Brandklipparen, but the officers see blood dripping from his left boot.

The wound gets infected and fills with yellow pus. Karl has a fever.

“The king probably has less than a day to live,” writes an army doctor to General Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld.

Russian spies report to Tsar Peter that the Swedish king is wounded. At sunrise on June 28, 1709, Peter arrives in Poltava with reinforcements. He is confident of his victory.

From an elevated position, the equestrian king looks around at his troops, which are lined up in battle formation. He sees through binoculars how enemy infantrymen in blue uniforms with yellow belts raise muskets with bayonets and begin to advance.

The king cannot lead the attack; he lies on a stretcher, carried by a pair of horses.

There are twice as many Russians and they are better armed.

The Carolinians are marching towards death. Burning cannonballs, flying fragments, and buckshot tear people and horses to pieces. The guns roar, and the king from his observation post sees how the Swedes' line is thinning.

Of the Uppland regiment, consisting of seven hundred people, only 14 survived.

At eleven o'clock the king takes off his hat in a gesture of victory. The Swedes are defeated. Poltava was the end of Swedish greatness.

Charles XII went to battle with 19 thousand Carolinians. Almost half - 9,700 people - died or were captured.

The king flees to Bendery. On July 1, 1709, General Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt capitulated at Perevolochna.

Charles XII rules the state from afar

Bendery is a city on the Dniester River in the territory of the current Republic of Transnistria between Moldova and Ukraine. During the time of Charles XII the city was part of the Ottoman Empire. Karl remains there for several years along with the Carolinians who survived the Battle of Poltava.

In the village of Varnitsa, a few kilometers from the city walls, a small town of its own is being built, which the Swedes call Karlopolis.

The main building is Charles's House with thick brick walls. The 35-meter-long structure has one floor, the roof is covered with sawdust, and large windows let in a gentle breeze on hot summer days.

Within the protective structures there is another house - the Great Hall. From there, King Charles XII rules his state in the far north of Europe. All orders are sent to Sweden by messenger.

The king is an autocratic monarch, and the advisers in Stockholm cannot decide anything without his approval. Every now and then messengers arrive from Stockholm with papers requiring the royal signature.

We are talking either about the appointment of vicars, or about the construction of a new royal palace. Everything requires the king's resolution.

Charles XII is a political refugee, an exiled king, and between him and his defeated power stand powerful enemy forces, just waiting to put an end to him.

The Sultan and the King have a common enemy

Without funds, ingloriously defeated by Tsar Peter, King Charles XII lives under the protection of the 35-year-old Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Ahmed III.

The Sultan is forced to receive the king as a guest. Turkey, or the Ottoman Empire as it was called, was the largest state on the continent, comprising what is now Turkish territory, the African Mediterranean coast, the Middle East, and the region around the Persian Gulf.

For 25 million subjects, Ahmed is a demigod; he is called the shadow of God on earth. He lives in Topkapi Palace (now a museum) on a hill where the Golden Horn separates the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara. His city is called Constantinople (now Istanbul).

Ahmed III allows Charles XII to stay in Bendery. The reason is that they have a common enemy, Tsar Peter.

Peter, later called the Great, is a warlike ruler who poses a threat to both the Swedish state and the Ottoman Empire.

The two rulers believe that together they can defeat the increasingly powerful Russian bear.

You just have to wait for the right moment.

Kalabalyk in Bendery

Five years pass. The Sultan already considers Charles XII a freeloader whose maintenance is too expensive. Besides, Karl is practically powerless.

Tsar Peter offers peace to the Sultan. Ahmed III secretly gives the commandant Bender Ismail Pasha the order to expel the Swedes.

February 1, 1713. The king has just listened to the Sunday sermon of the court priest Johannis Brenner in the great hall of Charles's house.

Through the open windows you can hear the beating of drums and loud calls to Allah. The Turks are coming.

Guns roar, burning arrows whistle in the air, a combat alert. The king runs out into the courtyard with a sword in his hand, and the Drabants barely hear his cry through the roar of the cannons:

“It’s not time to chat, it’s time to fight.”

The French philosopher Voltaire, a devoted admirer of the king, writes in his biography of Charles XII that he impaled four floundering Turks on his sword with one blow.

This is probably not true. But the king shows great courage, or perhaps recklessness, in battle against superior enemy forces.

In dangerous moments, the young lifeguard Axel Erik Roos saves the king's life three times.

Our history books describe this day in awkward footnotes, and we learn a new word: kalabalyk is “turmoil” in Turkish.

Execution as a way to apologize

Just a few days later the Sultan changes his mind. He received a message from Europe that General Magnus Stenbock had defeated the Danish king Frederick IV at the Battle of Gadebusch in Vorpommern. The Carolineers still have gunpowder in their flasks. It's not all over with King Charles.

The Battle of Gadebusch was the last major victory of the Swedish great power. But then no one knew about it.

Charles XII is again in the favor of the Sultan, he is released from captivity.

But fate turned away from Ismail Pasha. His severed head is mounted on a pike and exposed to dry in the sun in the Seraglio of Constantinople, just on the day that the Swedish messenger arrives there. Everyone who took part in the attack on the king is executed or sent away.

This is the Sultan's way of apologizing. Charles XII remains in Turkey for some time.

The Carolinians brought cabbage rolls with them

The king and the Carolinians remained in Bendery in the Ottoman Empire for several years. They fell in love with the local cuisine, especially the dish that the Turks call “dolma”. It was prepared in the oriental way, with grape leaves and without pork (it is prohibited for Muslims).

We don't have grape leaves, so when we got home, the Caroliners would wrap the minced meat in scalded cabbage leaves. This is how our favorite homemade dish appeared - cabbage rolls. On November 30, the day of the death of Charles XII, Cabbage Rolls Day is celebrated.

In addition, the Carolinians brought meatballs (Turkish kofta), coffee and the word “kalabalik” from Turkey.

A single shot rang out in silence

In the autumn of 1713, Charles XII left his place of exile and began his long journey home. He realized that the wait was not worth it. He would never lead the Swedish-Turkish army in battle against Peter the Great.

The king is eager to take revenge, he has new plans. Sweden is blocked by enemy fleets. We must force Denmark to submit and thereby break the blockade.

Finland and Swedish possessions in Germany should be liberated.

Norway belongs to Denmark, and Charles XII's plan is to annex Christiania (Oslo) and the southern regions to Sweden.

A new army is being assembled, 65 thousand brave Carolinians.

Lieutenant General Carl Gustaf Armfeldt makes a dash across the Swedish mountains to occupy Trondheim. The main forces come from the south, having built a bridge across Svinesund.

Fredriksten Fortress is the key to success. If she falls, then Norway will fall, and the Danish kingdom will be halved. The fortress stands on a steep hill where the Triste River flows into Idefjord.

The fortress is under siege. Caroliners dig trenches in a semicircle, leaving room for cannons that should smash enemy walls into small pebbles.

November 30, 1718 - First Sunday of Advent. Between nine and ten o'clock in the evening the king comes out to inspect the positions. Cold and dark. The king wraps up his blue uniform and climbs out of the trench onto the crest of the parapet.

A single shot rings out in silence. The bullet pierces the king's left temple and exits the right. Charles XII dies.

The mysterious death of the king

On November 30, 1718, at eleven o'clock in the evening, Charles XII was killed by a bullet in a trench near the Norwegian fortress of Fredriksten.

The fatal bullet hit the king in the head.

Hitman among the Carolinians? Or a Norwegian shooter?

The death of Charles XII gave rise to much speculation.

In the Varberg Museum you can see the so-called bullet button. According to legend, the king was killed with a button from his own military uniform melted into a bullet. They say it was a war-weary Carolinian who shot his commander.

The king's grave was excavated several times to conduct forensic and ballistic examinations that could help solve the mystery.

The latest research, conducted in 2005 by historian Peter From, states that the king was killed by a Norwegian bullet. Both the direction and the distance between the Swedes and the Norwegian defenders of the fortress correspond to the nature of the wound in the king's head.

Who was Charles XII?

Was the king a hero or a war-crazed madman who led his kingdom to ruin?

Assessments changed as new political and cultural movements emerged in Sweden.

During the Romantic era of the 19th century, Charles XII was the invincible king of fate. As Esayas Tegner wrote in a poem that all today's schoolchildren learn, “he drew his sword from its scabbard and rushed into battle.”

In the 1910s, Charles XII became a symbol of strong royal power, as well as the resistance of right-wing politicians to democracy and universal suffrage (including for women).

During World War II, Charles XII was the favorite of the local Nazis, the Swedish Fuhrer.

There is a monument to Charles XII in the Royal Garden in Stockholm. In one hand he has a naked sword, with the other he points to the east, where his enemy is waiting.

On the day of his death, racists and Nazis gather at the monument.

Interestingly, neo-Nazis consider Charles XII a hero. The king was a fourth-generation migrant (his great-grandfather ended up in Sweden after the Thirty Years' War in what is now Germany). His mother was born in Denmark, which was then the sworn enemy of the Swedish state.

The state of Charles XII was multicultural, many nationalities, religions and languages coexisted in it. Charles XII's brother-in-arms was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and during the years spent in Turkey, the king learned to respect and even admire Islam.

Chronology

1697 - On December 14, the coronation of fifteen-year-old Charles takes place, he becomes the sole king of Sweden after a six-month reign of the regency government.

1700 - In February, the Great Northern War begins with the attack of Augustus the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony.

On September 13, Tsar Peter launches an attack on Sweden in the Baltic states.

On November 20, the Carolinians win a major victory at Narva.

1703 - The Bible of Charles XII is published - the first official translation, which remains in use for about 200 years until a new Bible appears in 1917.

1706 - September 14, Charles XII marches into Saxony and wins a great victory at Fraunstadt. On the same day, Charles XII and Augustus the Strong conclude the Peace of Altranstedt near Leipzig.

1708 - On September 28, the Russian troops of Tsar Peter defeat the Carolinians in the Battle of Lesnaya on the territory of modern Belarus.

1709 - June 28, Karl is defeated near Poltava. In the battle against Tsar Peter, eight thousand Carolinians die, three thousand end up in the hands of the enemy.

To escape the Russians, Charles XII flees to Bendery in the Ottoman Empire in August.

1713 - February 1, Sultan Ahmed III, who was tired of supporting Charles XII and his Carolinians, orders the Turks to attack the king’s camp in Bendery and expel the Swedes. Charles XII is captured.

1716 - From February to April, Charles XII fails in his attempt to capture Christiania (Oslo), which is under Danish rule.

1718 - In October, the Carolinians re-enter Norway and besiege the fortress of Fredriksten in Fredrikshalde (now Halden).

Data

Born: June 17, 1682 at Tre Krunur Castle.

Parents: Charles XI and Ulrika Eleonora of Denmark.

Children: no.

Coronation: at the age of 15.

Reign: 21 years.

Career: war and war again.

Died: November 30, 1718. The king was 36 years old.

Successor: Ulrika's sister Eleonora.

National Museum of Sweden. Painting by Gustav Cederström. Carrying the body of Charles XII across the Norwegian border, version 1884

Who and why killed Charles XII is still not known exactly - three centuries after his death on the battlefield

Autumn 1718. The Northern War, one of the largest military conflicts of the 18th century, has been going on for 18 years. The armies of Sweden, Russia, Denmark, Poland, England and other European countries met in it. The fighting covered a vast territory - from the Black Sea to Finland.

On November 12, 1718, a Swedish army led by 36-year-old King Charles XII besieged the well-fortified fortress of Fredrikshald - today the city of Halden in southern Norway. Three hundred years ago, the now independent country was a province of Denmark.

(In Sweden, until 1753, the Julian calendar was in effect and all dates in this article are indicated in accordance with it for reliability. The Gregorian calendar in the 18th century was “ahead” of the Julian calendar by 11 days. Thus, the siege of Fredrikshald began on November 23 in the Gregorian calendar. - approx. . author)

Within a couple of weeks it became clear that the capture of the fortress was only a matter of time. The city was shelled from three sides by 18 siege weapons, methodically destroying the fortifications. Fredrikshald was defended by only 1,400 Danish and Norwegian soldiers from the 40,000-strong Swedish army.

The Swedes built a system of trenches and sapper installations around the city, which allowed the besiegers to fire at the defenders of the fortress from a distance of only a few hundred steps (the metric system for measuring distances was not yet used at that time, and the length of a step in different countries corresponded to modern 77-88 centimeters).

The siege was led by Charles XII, an outstanding commander and an exceptionally brave man. On November 26, he personally led a detachment of 200 people to storm one of the Danish fortifications under the walls of the fortress. The king found himself in the center of hand-to-hand combat, he could easily have died, but he was not injured and left the battle only after the fortification was captured.

Karl himself supervised the engineering work and daily bypassed the Swedish positions within a few hundred steps of the Danish soldiers. The risk was enormous - one well-aimed rifle shot or a successful cannon salvo could deprive Sweden of its king. But this did not stop the monarch. He was bold to the point of recklessness. No wonder he was called “the last Viking.”

On the evening of November 30, the king, together with a group of officers, went on another inspection. From the trench, he spent a long time looking through the telescope at the walls of the fortress and gave orders to Colonel of the Engineering Service Philippe Maigret, who was standing nearby. It was already dark, but the Danes, in order to see the positions of the Swedes, launched bright flares. From time to time shots were heard as the defenders of Fredrikshald fired harassingly.

At some point, Karl wanted to get a better view. He climbed higher along the earthen parapet. Below, Maigret and the monarch’s personal secretary, Siquier, were waiting for new instructions. The rest of the retinue was also located nearby. Suddenly the king fell from the embankment. The officers ran up and found that Karl was already dead, and a huge through wound was gaping in his head. Legend has it that Maigret, upon seeing the murdered monarch, said: “Well, that’s all, gentlemen, the comedy is over, let’s go to dinner.”

The deceased was transferred to the headquarters tent, where the court physician Melchior Nojman embalmed the body.

The death of the king dramatically changed the plans of the Swedish command. Already on December 1, the siege of Fredrikshald was lifted and a hasty retreat from the city began, more like an escape.

Karl's body was taken on a stretcher across half of Scandinavia to Stockholm. This funeral procession is depicted in the painting “Carrying the Body of Charles XII Across the Norwegian Border” by Swedish artist Gustaf Cederström.

On February 15, 1719, the king was buried in Riddarholmen Church in Stockholm. Charles became the last European monarch to be killed in action. The throne was taken by his sister Ulrika Eleonora.

The hasty retreat from Fredrikshald did not allow a full investigation into the circumstances of the king's death. It was announced that he was killed by grapeshot fired from the Danish positions.

There were immediately people who questioned this version. The doubts turned out to be so strong that 28 years later, in 1746, the Swedish king Fredrick I ordered the opening of Charles’s grave to re-examine the body. The court physician Melchior Neumann carried out the embalming flawlessly, so the august deceased looked as if he had died quite recently.

The excellent preservation of the body made it possible to study in detail the wound on Karl’s head. Doctors and military personnel, well acquainted with the nature of combat injuries, made a stunning conclusion: a through hole in the skull the size of a pigeon egg was made not by a fragment of a grapeshot shell, as previously thought, but by a rifle bullet.

This immediately cast doubt on the version of the fatal shot from the Danish side. From the forward positions of the Swedish troops to the walls of the fortress there were about 300 steps. According to ballistics calculations, the probability of hitting a target measuring 1.2 x 1.8 meters from a smoothbore gun from the early 18th century from such a distance is only 25%, and the chance of hitting a person’s head from such a distance is much less.

It must also be taken into account that Karl was killed at night in the uneven light of engineering rockets, which would have further complicated the task of the Danish sniper. The wound on the skull turned out to be through, which indicates the high speed of the bullet, which persists only at a short distance. No traces of lead or other metal were found in the head.

If the monarch had been killed by a bullet that accidentally flew from the Danish positions, it would have lost its kinetic energy and lodged in the skull.

It would seem that the “Danish” version turned out to be untenable. But she received unexpected confirmation almost two centuries later.

It was said above how difficult it would be to hit Karl with a regular smoothbore musket. But in 1718, special serf guns already existed. These were heavy and bulky mechanisms with a barrel length of up to two meters and a weight of up to 30 kilograms. Such a gun is difficult to hold in your hands, so it was equipped with a wooden stand. The ammunition for it was conical lead bullets weighing 30-60 grams, and the range of destruction made it possible to pierce the skull even from a very long distance. Could it have been used to shoot Karl?

In 1907, a Swedish physician and amateur historian, Dr. Njustrem, conducted an experiment. Using old drawings, he assembled a serf gun and filled it with gunpowder, also made according to an 18th-century recipe. At the site of the death of the king, the doctor installed a wooden target the size of a human body, and he himself climbed the fortress wall of Fredrikshald, from where he shot 24 times. Nyström himself believed that the Danes could not hit Charles from such a distance even with a fortress gun and wanted to confirm this.

But the result of the experiment turned out to be exactly the opposite. The doctor hit the target 23 times, proving that a good shooter from the fortress wall could easily kill the king.

In 1891, Baron Nikolai Kaulbar from Estland (as Estonia was called at that time) stated that he kept the gun from which, according to family legend, Karl was shot. The aristocrat sent two photographs of the family heirloom and a cast of the bullet for examination to Stockholm.

The antique gun turned out to be a very remarkable artifact. For some reason, the names of courtiers from Karl’s inner circle, precisely those who were present at his death, were engraved on it.

The examination revealed that the rarity was released at the end of the 17th century, but it was not used to shoot the king. The monarch's terrible wound did not correspond to the bullets fired from Kaulbar's gun.

In 1917, the remains were again removed from the crypt (there were four exhumations in just three centuries) and examined using modern forensic techniques. For the first time, X-rays of the skull were taken.

The conclusions of experts turned out to be contradictory. On the one hand, the bullet hit the skull on the left and slightly behind, and, according to experts, could not have come from Fredrikshald. But on the other hand, the entrance hole was located slightly higher than the exit hole - the bullet moved along an inclined trajectory, from a hill, for example, from an embankment or .... walls. The second conclusion already allowed a shot from the fortress.

In 1924, a new artifact appeared. Norwegian Carl Hjalmar Andersson donated an old bullet to the museum of the Swedish city of Varberg, which, in his opinion, killed the monarch, but there was no evidence of this. According to legend, soldier Nilsson Stierna, who served in the Swedish army during the siege of Fredrikshald, saw the death of Charles, picked up the bullet that pierced the king’s skull, and kept it with him. Two centuries later, the artifact reached Andersson in a roundabout way.

It is noteworthy that the bullet was cast from a brass button, which was sewn onto soldiers' uniforms of the Swedish army. Those who believed that it was with this piece of metal that the monarch was killed turned to superstition for argumentation. Karl emerged unharmed from bloody battles so many times that many considered him to be under a spell. It was possible to kill him only with something unusual and close to the king. And what could be closer to a warlike monarch than the soldier’s uniform of his own army?

In 2002, DNA analysis was carried out at Uppsala University. The researchers compared biomaterials found on the bullet with a brain sample taken during the exhumation of the king's remains and the monarch's blood left on clothing kept at the Stockholm Historical Museum.

The result of the examination was again ambiguous. Over 284 years, the samples have changed greatly under the influence of the environment. Researchers have identified only general parameters of the genetic code. The conclusion was that the DNA found on the pool could belong to approximately 1% of the Swedish population, including Karl. Moreover, traces of DNA from two people were found on the metal, which further confused the researchers. In general, genetic testing has not clarified the historical mystery.

Over time, other facts emerged indicating that it was not Danish soldiers who killed Charles.

First, we need to briefly describe the political and economic situation of the early 18th century. For 18 years, the grueling Northern War had been going on, in which Sweden confronted almost half of Europe. In the early years of the conflict, Charles managed to inflict serious defeats on Russia, Denmark and Poland, but unsuccessful battles on land and sea followed.

The campaign against Russia in 1709 turned out to be a real disaster for the Swedish army. Karl suffered a crushing defeat near Poltava, where he himself was wounded and almost captured.

The king was completely absorbed in the war and was not at all concerned with the Swedish economy, which was in a deplorable state. He carried out the infamous monetary reform, in which silver coins were equal in value to copper ones. This helped cover military expenses, but caused a sharp rise in prices and impoverishment of the population. The Swedes hated the financial innovations so much that the “author” of the reform, German baron Georg von Görtz, was arrested and executed three months after Karl’s death.

The aristocrats repeatedly asked the king to begin peace negotiations. In 1714, the Swedish parliament (Riksdag) even adopted a special resolution on this matter, which was sent to the monarch, who was in Turkey at that time.

Karl rejected him and, despite the defeats and economic problems, decided to continue the war to a victorious end. For such stubbornness, the Turks gave him another telling nickname - “Iron Head”. Since 1700, the monarch practically did not appear in his homeland, spending his life on endless campaigns.

The German scientist Knut Lundblad, in his book “The History of Charles XII,” published in 1835, put forward a version of the involvement of the English king George I in the murder of his Swedish colleague. At the beginning of the 18th century, George fought with the pretender to the throne, Jacob Stuart. In 1715, the confrontation led to the Jacobite uprising, which was suppressed by royal troops.

Lundblad suggested that Charles XII was going to help James by sending an expeditionary force of 20 thousand soldiers to England to fight George. And the current English king decided to prevent this by organizing the murder of Charles. This version has one weak point - Sweden, with all its desire, could not, either in 1718 or in subsequent years, land a large amphibious assault in England. After unsuccessful naval battles with Russia and Denmark, the Scandinavian kingdom lost most of its fleet. George did not have to fear a Swedish invasion.

However, both inside and outside Scandinavia there were many influential people who wanted Charles dead.

Knut Lundblad also described such a story. In December 1750, Baron Carl Cronstedt, one of the best officers of Charles XII, died in Stockholm. He invited a priest to confess.

The dying man admitted that he had participated in a plot to kill Charles and demanded that the pastor go to another officer, Magnus Stierneroos, who also served under the late monarch.

Cronstedt stated that it was Stierneros, his former subordinate, who shot the king. The baron considered his own confession insufficient and wanted to convince another officer involved in the murder to repent.

Stierneros, after listening to the priest, said that Kronstedt was clearly not himself and did not understand what he was saying. The pastor conveyed the answer to the baron, to which he explained in detail what kind of gun Karl was killed with. It, according to Kronstedt, was still hanging on the wall of Stierneros’ office. The priest again went to the latter asking for a confession, but the officer, in a rage, drove the pastor out of his house.

This story would have remained unknown, because the priest has no right to divulge what he heard during confession. He described the unusual altercation between the two officers in his diary, which he did not show to anyone. In 1759, the pastor died and his notes were made public.

The murder of Charles, according to the dying Kronstedt, occurred as a result of a conspiracy by the Swedish aristocracy, dissatisfied with the king's policies. The baron recruited Stierneros, his subordinate and an excellent marksman, as the direct executor of the murder.

On the evening of November 30, he followed Charles and his retinue through the trenches, then climbed out of the trench and took a position in front of the earthen embankment, to which the monarch approached from the other side. Stierneros waited until the king looked out from behind the parapet and fired. In the confusion that followed the murder, he quietly returned to the trenches.

Kronstedt also admitted that he and other military leaders, after the death of Charles, behaved in a completely unnoble manner - they appropriated the entire military treasury. Stierneros also received a very substantial monetary reward and subsequently rose to the rank of cavalry general.

The information contained in the notes of the late priest had no confirmation and could not serve as legal evidence. But it is known that in 1789, the Swedish king Gustav III, in a conversation with the French ambassador, said that he considered Kronstedt and Stierneros to be the perpetrators of the murder.

Karl's personal secretary, Frenchman Sigur, is also considered another suspect. Allegedly, it was he who shot the king. In Sweden, many believed this version. Indeed, shortly after the murder, a Frenchman in Stockholm, in a fit of delirium tremens, shouted that he had killed the king and asked for forgiveness for it.

Many years later, the famous French philosopher Voltaire, who wrote a biography of Charles, spoke with Sigur, then already a very old man, in his home in France. He said that the confession was false and was made due to a painful clouding of reason. Sigur respected Karl very much and would never dare to harm him.

After this, Voltaire wrote: “I saw him shortly before his death and I can assure you that not only did he not kill Charles, but he himself would have allowed himself to be killed a thousand times for him. If he were guilty of this crime, it would, of course, be for the purpose of rendering a service to some state, which would reward him well. But he died poor in France and needed help."

Different opinions about the direct perpetrator were discussed above, but who was the organizer of the conspiracy, if one did take place?

The involvement of the English King George is unlikely. He didn't have enough reason to kill.

The biggest winner from Charles's death was Fredrick of Hesse, the husband of his sister Ulrika Eleonora, who took the throne immediately after her brother's death. In 1720, she renounced the crown in favor of her husband. Fredrik ruled Sweden until his death in 1751. Many conspiracy theorists believe he was the organizer of the murder.

But perhaps all these conclusions are incorrect and Karl died from an accidental bullet fired from the walls of Fredrikshald. A new examination of the remains using the most modern technical means could solve the mystery.

In 2008, Stefan Jonsson, a professor of materials science at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, spoke to the BBC about the need for a new exhumation, the fifth in a row. The scientist is going to study the bones using an electron microscope.

“Even if there are the slightest traces of metal, we can study their chemical composition,” the professor said. However, permission for the next exhumation of the remains of the “last Viking” has not been received to this day.

Text: Sergey Tolmachev

XII Carl XII Career: Rulers

Birth: Sweden, 17.6.1682

The decisive role in achieving victory at Narva in 1700 undoubtedly belonged to King Charles XII. He carried out the unexpected arrival of the Swedish army near Narva for the Russians. He is the main organizer of the battle. With his immense thirst for battle and courage, and personal example, he inspired his warriors. They believed in him and worshiped him. It has long been known: courage is the beginning of victory. In the battle near Narva, the 18-year-old Swedish king showed off his talent as a commander, extraordinary military success and happiness, he covered Swedish weapons with glory.

In 1700, Denmark, Poland and Russia began the Northern War against Sweden. The 28-year-old Russian Tsar Peter I led a 32,000-strong army to Narva and besieged the city.

The Swedish throne was then occupied by the 18-year-old King Charles XII - an extraordinary and controversial person. He was born on June 17, 1682. His dad Charles XI left his son a first-rate European kingdom with a strong economy, an excellent system of government, a strong army and navy, and extensive overseas possessions outside the metropolis. He died in 1697, when his son was 15 years old.

Having become king, Charles XII got rid of guardianship after 7 months and became a sovereign monarch. The young king was a warrior by vocation; already at the age of 7 he dreamed of military campaigns, envied the glory of Alexander the Great and persistently prepared himself for this field. He despised luxury, walked without a wig, in a simple blue uniform, observed military order, developed extraordinary strength in himself through gymnastics, paid special attention to the art of war and the use of all types of weapons, loved hunting bears and other animals, was hot-tempered and quick-tempered, inflamed as powder.

He was not afraid of the triple alliance of states and the upcoming battle. On April 13, 1700, the king left Stockholm, announcing to his relatives that he was going to have fun at Kungser Castle, and he himself, with a 5,000-strong army on ships, rushed to the Danish shores. He took Denmark by surprise, and under the threat of the destruction of Copenhagen, the Danish king Frederick IV was forced to make peace. Denmark left the war.

Having dealt with one enemy, the king rushed to besieged Riga. The Polish king Augustus II, fearing the approaching Swedes, lifted the siege of the city on September 15 and retreated without a fight.

Now the Swedes were waiting for Narva, besieged by Russian troops. On September 20, 1700, a Swedish flotilla consisting of 9 ships and two frigates raised sails in Karlskrona and moved to the shores of Estonia. On September 25, the squadron arrived at the port of Pernov (today Pärnu). Approaching the shore on the yacht "Sofia", the king was so inflamed with the desire to reach it quickly that he lost caution and was prevented from drowning. The brave General Renschild saved him.

The young king's thirst for battle and self-confidence knew no bounds.

Do you really think that 8,000 brave Swedes cannot cope with 80,000 Moscow men? - he declared to his entourage.

On November 19, 1700, by noon, the Swedes deployed their battle formations in front of the positions of the Russians besieging Narva. Before the battle, in full view of his army, Charles XII dismounted from his horse, knelt down, said a prayer for victory, hugged the generals and soldiers standing nearby, kissed them, and mounted his horse. Exactly at 2 o'clock shouting:

God is with us! - The Swedes rushed to attack.

The balance of forces was as follows: Russians - 32,000, Swedes - 8,000. At the very beginning of the battle, the middle of the Russians was crushed, their disorderly retreat and flight began. On the left flank, Weide's division, retreating, began to push Sheremetev's mounted militia towards the waterfalls. The stormy Narova and its waterfalls swallowed up more than 1000 riders and horses. On the right flank, Golovin's division, retreating in panic, rushed to the floating bridge. It couldn't bear the load and burst. And then the waves of the Narova swallowed up their victims en masse. To this the king remarked contemptuously:

There is no pleasure in fighting with the Russians, due to the fact that they do not resist, like others, but run.

Only the Preobrazhensky, Semenovsky and Lefortov regiments and the gunners-artillerymen steadfastly repelled the attacks of the Swedes. The king was undaunted; fighting was his element. There, in the thick of the battle, he himself led his warriors to attack several times. During the battle, the king fell into a swamp, got stuck with his horse in a quagmire, lost his boot and sword, and was rescued by his retinue. The bullet hit him in the tie. A cannonball killed a horse underneath him. Surprised by the steadfastness of the three Russian regiments, the king exclaimed:

What men are like!

The losses of the young, poorly trained, untested Russian army in battles were enormous: 6,000 killed, 151 banners, 145 guns, 24,000 guns, the treasury and the entire baggage train. Many foreign generals and officers, led by the commander Duke de Croix, surrendered to Charles XII. The Swedes lost 1200 men.

Victory, as we know, is always attributed to the talent of the commander and the courage of the soldier, and the defeat is explained by a fatal accident. The decisive image in achieving victory at Narva in 1700 undoubtedly belonged to King Charles XII. He carried out the unexpected arrival of the Swedish army near Narva for the Russians. He is the first organizer of the battle. With his immense thirst for battle and courage, and personal example, he inspired his warriors. They believed in him and worshiped him. It has long been known: courage is the beginning of victory. In the battle near Narva, the 18-year-old Swedish king showed off his talent as a commander, extraordinary military success and happiness, he covered Swedish weapons with glory.

On November 22, 1700, accompanied by a brilliant retinue, Charles XII and his troops sublimely entered Narva. A thanksgiving prayer service was held in the church. The celebration of the winners was accompanied by the firing of cannons and rifles. Rudolf Horn, who led the defense of Narva Genting, was promoted to general. In honor of the victory, 14 medals were knocked out, incl. two are satirical. One of them depicts a crying Tsar Peter I running from Narva, his hat falls from his head, the blade is thrown away, the inscription: “He went out, he cried bitterly.”

The victory turned the head of the young victorious king; he believed in God’s providence. He had a map of Russia hanging in his bedroom, and he showed his generals the road to Moscow, hoping to quickly and easily reach the heart of Russia. General Stenbock:

The king thinks about nothing more than war, he no longer listens to advice; he takes on such an appearance, as if God directly inspires him that he must work.

Charles XII mistakenly considered Russia to be out of the war and refused a profitable peace with it.

In 1701, Charles XII decided which of the unfinished enemies to deal with, because victory in battle is not yet victory in war. The choice fell on the king of Poland, the Saxon elector Augustus P. Having won a few victories in battles, he managed to oust Augustus II from Poland, deprive him of the royal crown, and impose on the Poles a new king, Stanislav Leszczynski, who had previously been the Poznan voivode. Poland then became an ally of Sweden. All this took a few years.

At this time, having recovered from the Narva defeat, the Russian Armed Forces began to win victory after victory on the shores of the Baltic Sea (Erestfer near Dorpat, Noteburg, Nyenschanz, Dorpat, Narva, etc.). Despite this, Charles XII's self-confidence continued to remain boundless. Having received news of construction. Peter I of St. Petersburg, the king grinned:

Let him build. Everything will be the same.