§16. Mongol invasion of Rus'

Chapter 7. THE MONGOL INVASION AND THE FATE OF THE EASTERN SLAVS IN THE XIII century.

§ 1. MONGOL CONQUESTS

In the middle of the 13th century. The territory of North Asia was engulfed by events that led to fundamental changes in the development of both the entire region as a whole and Ancient Rus'.

Formation of the Mongolian state. In the second half of the 12th century. On the lands of numerous Mongolian tribes (Kerits, Taijuns, Mongols, Merkits, Tatars, Oirats, Onguts, etc.), wandering from Lake Baikal and the upper reaches of the Yenisei and Irtysh to the Great Wall of China, the process of decomposition of the clan system intensified. Within the framework of clan ties, property and social stratification occurred with the promotion of such an economic unit as the family to the fore. The steppe Mongols based their economy on cattle breeding. In conditions when the steppes were common, a custom developed to transfer ownership of pastures by the right of primary seizure by one or another family. This made it possible to identify wealthy families who owned countless herds of horses, large and small livestock. This is how the nobility (noyons, bagaturs) were formed, new associations were created - hordes, all-powerful khans appeared, squads of nukers were formed, which were a kind of guard of the khans.

The peculiarity of the existence of the nomadic Mongols was a traveling lifestyle, when a person from childhood did not part with a horse, when every nomad was a warrior, capable of instant movement over any distance. Plano Carpini in the History of the Mongols (1245-1247) wrote: “Their children, when they are 2 or 3 years old, immediately begin to ride and control horses and gallop on them, and they are given a bow according to their age, and they learn to shoot arrows, for they are very dexterous and also brave.” They learned the science of fighting by themselves. Unpretentiousness in everyday life, endurance, the ability to act without having a minute of sleep or a crumb of food for three or four days, a warlike spirit - all these are characteristic features of the ethnic group as a whole. Therefore, social stratification, the formation of the nobility, and the emergence of khans smoothly shaped the nascent state as a militarized one. In addition, the basis of the life of nomads - cattle breeding - organically assumed the extensive use of pastures, their constant change, and periodically the seizure of new territories. The primitiveness of the life of the nomads came into conflict with the demands of the established elite, which potentially prepared society for wars of conquest.

By the end of the 12th century. Inter-tribal struggle for supremacy reached its climax. Intertribal alliances and confederations were created, some tribes subjugated or exterminated others, turned them into slaves, and forced them to serve the winner. The elite of the victorious tribe became multi-ethnic.

So, in the middle of the 12th century. The leader from the Taichiut tribe, Yesugei, united most of the Mongolian tribes, but the Tatars hostile to him managed to destroy him, and the political union (ulus) that had barely emerged disintegrated. However, by the end of the century, Yesugei's eldest son Temujin (named after the Tatar leader killed by Yesugei) managed to subjugate part of the Mongol tribes again and become khan. A brave warrior, distinguished by courage, cruelty, and deceit, he, avenging his father, defeated the Tatar tribe. The “Secret Legend” reports that “all the Tatar men taken prisoner were killed, and the women and children were distributed among different tribes.” Part of the tribe survived and was used as a vanguard in subsequent grandiose military actions.

At the kurultai, a congress that met on the Onon River in Mongolia in 1206, Temujin was proclaimed ruler of “all the Mongols” and took the name Genghis Khan (“great khan”). Like previous associations of nomads, the new empire was characterized by a combination of tribal division with a strong military organization based on decimal division: a detachment of 10 thousand horsemen (“tumen”) was divided into “thousands”, “hundreds” and “tens” (and this the cell coincided with a real family - ail). The Mongol army differed from previous nomadic armies in its particularly harsh and harsh discipline: if one warrior out of a dozen fled, the entire ten were killed; if a dozen retreated, the entire hundred were punished. The usual execution is breaking the spine or removing the heart of the offender.

One of the first objects of expansion were the peoples living in the steppe and (partially) forest zone of Siberia: Buryats, Evenks, Yakuts, Yenisei Kyrgyz. The conquest of these peoples was completed by 1211, and the campaigns of Mongol troops began in the rich lands of Northern China, ending with the capture of Beijing (1215). Vast territories with an agricultural population came under the rule of the Mongol nomadic nobility. With the help of his Chinese advisers, Genghis Khan began to create an organization for their management and exploitation, which was then used in other conquered lands. The conquests in China gave the Mongol rulers access to battering and stone-throwing machines, which made it possible to destroy fortresses inaccessible to the Mongol cavalry. Genghis Khan's army increased significantly in size due to the forced inclusion of warriors from among the nomadic tribes that submitted to the Mongols. In the early 20s. XIII century Genghis Khan's troops, numbering 150-200 thousand people, invaded Central Asia, devastating the main centers of Semirechye, Bukhara, Samarkand, Merv and others and subjugating this entire vast region to their power. In Northern Eurasia, a huge, multi-ethnic state was emerging, headed by the Mongol nobility - the Mongol Empire.

The first war between the Mongols and Russia. After the conquest during 1219-1221. In Central Asia, a 30,000-strong Mongol army led by military leaders Jebe and Subedei went on a reconnaissance campaign to the West. Having defeated Northern Iran in 1220, the Mongols invaded Azerbaijan, part of Georgia and, having ruined them, deceived them through the Derbent Pass into the North Caucasus, where they defeated the Alans, Ossetians and Polovtsians. Pursuing the Polovtsians, the Mongols entered Crimea. In the fight against them, the Polovtsian association near the Don, led by Yuri Konchakovich, was defeated, and the defeated fled to the Dnieper. Khan Kotyan and the heads of other Polovtsian hordes requested support from the Russian princes. The Galician prince Mstislav Udatny (i.e. lucky), Kotyan's son-in-law, made an appeal to all the princes. As a result, the assembled army was led by the Kiev prince Mstislav Romanovich. The Smolensk, Pereyaslav, Chernigov and Galician-Volyn princes took part in the campaign. To fight the Mongol army, most of the military forces that were available at the beginning of the 13th century were assembled. Ancient Rus'. But not everyone took part in the campaign; in particular, the Suzdal regiments did not come. On the Dnieper, Russian troops united at Oleshya with “the entire Polovtsian land.” But there was no unity in this large army. The Polovtsians and Russians did not trust each other. The Russian princes, competing with each other, each sought to win on their own. The advanced regiment of the Mongols was defeated by Mstislav Udatny and Daniil Volynsky, but when the Mongols met the allied army on May 31, 1223 in the Azov steppes on the Kalka River, Mstislav Galitsky, together with the Polovtsians, entered the battle without informing the other princes, and the Polovtsians fled Mongols, “the prince trampled the fleeing camps of the Russians.” The head of the campaign, Mstislav Romanovich, did not take part in the battle at all, entrenching himself with his regiment on a hill. >After three days of siege, the army surrendered on the condition that the soldiers would have the opportunity to ransom from captivity, but the promises were broken and the soldiers were brutally killed; barely a tenth of the army survived. The Mongols left, but these events showed that the military forces of the scattered Russian principalities were unlikely to be able to repel the main forces of the Mongol army. For many centuries, the Russian people retained in their memory the bitterness of this defeat.

Mongol-Tatar invasion. The decision to march the Mongol troops to the West was made at a congress of the Mongol nobility in the capital of the Mongol Empire - Karakorum in 1235 after the death of Genghis Khan, although a preliminary discussion took place in 1229. The eldest grandson of Genghis Khan Batu (Batu of ancient Russian sources) became the head of these troops. , Subedey, who won the Battle of Kalka, became his main adviser. The huge army (according to Plano Carpini, 160 thousand Mongols and 450 thousand from the conquered tribes) mainly consisted of cavalry, divided into tens, hundreds and thousands, united under a single command and operating according to a single plan. It was reinforced with flamethrower and stone-throwing weapons, as well as battering machines, against which the wooden walls of Russian fortresses could not resist.

In 1236, the Mongol commander Burundai attacked Volga Bulgaria. The capital of the state - the “great city of Bulgaria” - was taken by storm and destroyed, and its population was exterminated. Then it was the Cumans' turn. In 1237, one of the main Polovtsian khans, Kotyan, with a 40,000-strong horde, fleeing from the Mongols, fled to Hungary. The Polovtsy, who remained in the steppe and submitted to the new government, became part of the Mongol army, increasing its strength. In the autumn of 1237, Mongol-Tatar troops approached the territory of North-Eastern Rus'.

Although the impending danger was known in advance, the Russian princes did not enter into an agreement among themselves on joint actions against the Mongols. The first to confront them were the Ryazan princes, who were initially presented with an ultimatum: to pay off tithes in men, horses and armor. However, the princes decided to defend themselves and turned to the Grand Duke of Vladimir Yuri Vsevolodovich for help. But he “didn’t go himself, nor listen to the Ryazan princes’ prayers, but he himself wanted to start a fight.” The Chernigov prince also refused help. And therefore, when Batu’s troops invaded the Ryazan land in the winter of 1238, the Ryazan princes, after defeat in the battle on the Voronezh River, were forced to take refuge in fortified cities. The Russian people bravely defended themselves. So, the defense of the capital of the Ryazan land - the city of Ryazan - continued for six days. Suffering serious losses, the Mongol commanders resorted to deception. According to the Ipatiev Chronicle, the main Ryazan prince Yuri Igorevich, who took refuge in Ryazan, and his princess, who was in Pronsk, they were “led out of these cities by flattery,” i.e. lured out by deception, promising honorable terms of surrender. When the goal was achieved, the promises were broken, the main centers of the Ryazan land were burned, their population was partly killed, partly driven into slavery. Subsequently, when it was not possible to overcome the defenses of Russian cities, the Mongols repeatedly resorted to this technique. And “not one of the princes... went to each other’s aid.”

Part of the Ryazan troops, led by Prince Roman Ingvarevich, managed to retreat to Kolomna, where they united with the army of governor Eremey Glebovich, who had arrived from Vladimir. Under the walls of the city at the beginning of 1238, “there was a great slaughter.” The Russian people “fought hard”; one of the “princes” - the grandchildren of Genghis Khan, who participated in the campaign - died in battle. From captured Kolomna, the Mongol-Tatars moved towards Moscow. The Muscovites, led by Philip Nyanka, showed courage, but the forces were unequal, the city was taken, “and the people were beaten from an old man to a mere baby.” Immediately the Mongol-Tatars invaded the lands of the Vladimir great reign. Yuri Vsevolodovich went north to Yaroslavl to gather a new army, and on February 3, 1238, the Mongols besieged the capital of the region - Vladimir. A few days later the walls of the city were destroyed, on February 7 the city was taken and devastated, the population was driven into slavery, the wife of Grand Duke Yuri, his children, daughters-in-law and grandchildren, and the Vladimir Bishop Mitrofan and his clergy died in the fire in the Assumption Cathedral. Having burst into the burning temple, the adversaries destroyed the main “wonderful icon, decorated with gold and silver and precious stones.” The Nativity Monastery was destroyed to the ground, and Archimandrite Pachomius and the abbots, monks and residents of the city were killed or captured. Yuri's sons also died.

Mongol-Tatar detachments dispersed throughout North-Eastern Rus', reaching in the north as far as Galich Mersky (Kostroma). During February 1238, 14 cities were ravaged and burned (among them Rostov, Yaroslavl, Suzdal, Tver, Yuryev, Dmitrov, etc.), not counting settlements and graveyards: “and there is no place, no village, no villages, dances are rare, where you didn’t fight on Suzhdal land.” On the Sit River on March 4, 1238, Grand Duke Yuri died; his hastily assembled but brave regiments, fighting desperately, could not break the strength of the huge Mongol army. Yuri's nephew Vasilko Konstantinovich was captured in the battle. The Mongols for a long time forced him in the Sherensky forest to go over to the enemy’s camp and “be in their will and fight with them.” The young prince rejected all offers and was killed. The chronicler wrote about him: “Vasilko’s face is red, his eyes are bright and menacing, he is braver than his best, light at heart, and affectionate to the boyars.” Another part of Batu's army moved west.

On March 5, 1238, Torzhok was taken and burned, but the city was delayed by the Mongol army for two whole weeks, and its heroic defense saved Novgorod. Due to the upcoming spring thaw, the Mongol-Tatars were forced to turn back before reaching the city. Through the eastern lands of the Smolensk and Chernigov principalities, they moved to the “Polovtsian land” - the Eastern European steppes. On this route, the Mongols encountered stubborn resistance from the small town of Kozelsk, whose siege lasted 7 weeks. When the city fortifications were destroyed, residents on the streets “cut knives” with the Mongols. The Goats cut down their battering guns, killed, as the chronicle reports, four thousand, and were themselves killed. During the capture of the city, the sons of three Temniks, major Mongol-Tatar military leaders, died. And again Batu’s warriors razed the city from the face of the earth and killed its inhabitants, down to the “adolescents” and “those sucking milk.”

The following year, 1239, the Mongols conquered the Mordovian land, and their troops reached Klyazma, again appearing on the territory of the Great Reign of Vladimir. Fear-stricken people ran wherever they could. But the main forces of the Mongol-Tatars were directed towards Southern Rus'. Impressed by what happened in the north of Rus', the local princes did not even try to gather forces to repel them. The most powerful among them - Daniil Galitsky and Mikhail Chernigovsky, without waiting for the arrival of the Mongols, went to the west. Every land, every city fought desperately, relying on their own strength. On March 3, Pereyaslavl South was stormed and destroyed, where Batu killed all the inhabitants, destroyed the Church of the Archangel Michael, seizing all the gold utensils and precious stones and killing Bishop Simeon. In October 1239 Chernigov fell. In the late autumn of 1240, Batu’s army “in great strength” besieged Kyiv with “many multitudes of its strength.” The chronicler writes that “from the creaking of his carts, the multitude of roaring of his velvets and the neighing of his horse from the sound of herds,” the voices of the people defending the city were not heard. The chronicle also notes that the Mongol military leader, sent a year before the siege to “look” at Kyiv, “seeing the city, was surprised at its beauty and its majesty.” The Kyivians rejected the proposals for surrender coming from the military leader. Here the Mongols encountered particularly stubborn resistance, although at the end of 1239 Kiev was left without a prince, since Mikhail of Chernigov, who was sitting in Kiev, fled to the Hungarians, and Rostislav of Smolensky, who occupied the Kiev throne, was captured by the Galician prince Daniil. Daniel installed the governor Dmitry in Kyiv. Having begun the siege, Batu concentrated battering guns, which struck day and night, in the area of the Lyash Gate. The townspeople desperately defended themselves on the walls. When the walls of the city were destroyed by battering machines, the residents of Kyiv, led by Voivode Dmitry, set up a new “hail” around the Tithe Church and continued to fight there. The vaults, which collapsed from the weight of many people running up to the church, became the grave for the last defenders of the capital of Ancient Rus'.

Having taken Kyiv, the Mongols moved to the Galicia-Volyn land and took Galich and Vladimir Volynsky by storm, the inhabitants of which were “beaten without sparing.” “Innumerable cities were devastated.”

Already this rather brief description of the events shows how the Mongol invasion with its huge, superbly equipped army differed from those traditional raids of nomads to which the ancient Russian lands were subjected in previous centuries. Firstly, these raids never covered such a vast territory, because huge regions were devastated (such as North-Eastern Rus'), which had not previously been subject to raids by nomads. The Pechenegs and Polovtsians, capturing booty and prisoners, did not set as their goal the capture of Russian cities, and they did not have the appropriate means for this. Only occasionally did they manage to capture one or another minor fortress. Now the main cities of many ancient Russian lands were completely destroyed and lost most of their population. Nowadays, in the cultural deposits of many ancient Russian cities of the mid-13th century. Archaeologists have discovered layers of continuous fires and mass graves of the dead. Of the 74 ancient Russian cities studied by archaeologists, 49 were devastated by Batu’s troops, in 14 of them life ceased altogether, 15 turned into rural-type settlements. The merciless extermination and captivity of the masses of skilled artisans led to the fact that a number of branches of handicraft production ceased to exist. In particular, a huge lack of funds and skilled labor led to the cessation of stone construction in the country for a number of decades. The first stone building that appeared in North-Eastern Rus' after the Mongol invasion was the Cathedral of the Savior in Tver, erected only in 1285. The process of restoration after enormous destruction by the forces of a society with a traditionally limited total surplus product was extended over many decades and even centuries.

Having bled, deprived the ancient Russian lands of a significant part of the population, and destroyed the cities, the Mongol invasion threw the ancient Russian society back at the very moment when progressive social transformations began in the countries of Western Europe associated with the development of internal colonization and the rise of cities.

§ 2. EASTERN SLAVS UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE GOLDEN HORDE AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH WESTERN NEIGHBORS

Establishment of the yoke of the Golden Horde. However, the negative consequences of the changes that took place were far from limited to this. After the return of the Mongol army from a campaign in the countries of Western Europe, the ancient Russian lands became part of the “Batu ulus” - possessions subordinate to the supreme power of the grandson of Genghis Khan and his descendants. The center of the ulus became the city of Saray (“barn” translated into Russian as “palace”) in the lower reaches of the Volga, by the middle of the 14th century. numbering up to 75 thousand inhabitants. Initially, Batu Ulus was part of the gigantic Mongol Empire, subordinate to the supreme authority of the Great Khan in Karakorum - the eldest among the descendants of Genghis Khan. It included China, Siberia, Central Asia, Transcaucasia, and Iran. Since the beginning of the 60s. XIII century the possessions of Batu’s successor, Berke, became an independent state, which, according to tradition in Russian literature, is called the Golden Horde (other names: “Ulus Jochi”, “White Horde”, “Deshti Kipchak”). The Golden Horde occupied a much larger territory than the nomads of the Pechenegs and Polovtsians - from the Danube to the confluence of the Tobol with the Irtysh and the lower reaches of the Syr Darya, including the Crimea, the Caucasus to Derbent. Along with the steppes - traditional places of nomadism - the Batu ulus also included a number of agricultural territories with developed urban life, such as Khorezm in Central Asia and the southern coast of Crimea. Rus' also belonged to the number of such lands. The power base of the khan was the nomads of the Eastern European and Western Siberian steppes, who fielded an army with which he kept dependent farmers in obedience. Already in the army that came from Batu, a significant part were made up of Turkic-speaking tribes of Central Asia, they were then joined by the Cumans, who submitted to the Mongol authorities. In the end, the Mongols disappeared into the mass of Turkic-speaking nomads, having adopted their language and customs. According to scientists, even court circles already from the end of the 14th century. They spoke Turkic. Official documents were also compiled in Turkic. The new people thus formed received the name “Tatars” in ancient Russian and other sources. The connection with Mongolian traditions was preserved only in the sense that only the descendants of Genghis Khan had the right to occupy the Khan’s throne; the people subsequently laid the foundation for the formation of the main Turkic ethnic groups in our country.

What were the main manifestations of the dependence of the ancient Russian lands on the Horde? Firstly, the Russian princes became vassals of the khan, and in order to rule his principality, the prince had to receive a “label” (letter) from the khan in Sarai, giving the right to reign. The first to go to Batu for a label in 1243 was the new Grand Duke of Vladimir, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, and other princes followed him to the Horde. The trip to get the tag was quite dangerous. In a difficult situation, Yaroslav had to leave his son Svyatoslav in the Horde as a hostage. And hostage-taking has now become quite common. And in 1245, Yaroslav was again summoned by Batu to Sarai and from there sent to Karakorum, where in 1246, after a meal with the great Khan Tarakina, he died on the way home. The fault, apparently, was suspicions of contacts with Western Catholics. In 1246, Prince Mikhail of Chernigov, who refused to go through the cleansing fire when visiting the Khan’s headquarters, was killed by the Tatars. From now on, in disputes between the princes, the khan acted as the supreme arbiter, whose decisions were binding. After the separation of the Batu ulus from the Mongol Empire, its head - the khan - on the pages of ancient Russian chronicles began to be called "the Caesar", as previously only the head of the Orthodox Christian world - the Byzantine emperor - was called.

The Russian princes were supposed to take part in campaigns with their troops on the orders of the khan. So, in the second half of the 13th century. A large group of princes from North-Eastern Rus' took part in campaigns against the Alans, who did not want to submit to the power of the Golden Horde.

Another important responsibility was the constant payment of tribute (“exit”) to the Horde. The first steps to register the population and organize the collection of tribute were taken immediately after the capture of Kyiv. Khan Guyuk ordered the registration of all residents for their partial sale into slavery and collection of tribute in kind. In 1252-1253 The Mongols conducted censuses in China and Iran. For better organization of tribute collection in the late 50s. XIII century A general census of the population (“number”) was also carried out on the ancient Russian lands subject to the Golden Horde. Far-sighted Mongol authorities, trying to divide the conquered society, exempted only the Orthodox clergy from paying tribute, who were supposed to pray for the well-being of the khan and his state. According to some sources, the Suzdal, Ryazan and Murom lands were originally described. According to the testimony of the Franciscan Plano Carpini, who visited the ancient Russian lands on the way to the Horde, the size of the “exit” was 1/10 of the property and 1/10 of the population, which in just 10 years was equivalent to the original amount of all property and the entire population. People who were unable to pay tribute, as well as those without families and beggars, were turned into slavery. In case of delay in payment of tribute, cruel punitive actions immediately followed. As Plano Carpini wrote, such a land or city is ravaged “with the help of a strong detachment of Tatars, who come without the knowledge of the inhabitants and suddenly rush upon them.” In many Russian cities, special representatives of the khan appeared - “baskaks” (or darugs), they were accompanied by armed detachments, and they, exercising political power on the spot, had to observe how the khan’s orders were carried out. At first they were also entrusted with collecting tribute. Over time, it was farmed out. In the XIV century. as a result of outbreaks of riots and unrest that swept across Russian lands in the second half of the 13th century. (uprisings of 1259 in Novgorod, 1262 in Yaroslavl, Vladimir, Suzdal, Rostov, Ustyug), Russian princes began to collect tribute to the Mongols.

Thus, the ancient Russian principalities not only lost their political independence, but also had to constantly pay a huge tribute to the country devastated by the invasion. Thus, the volume of the total surplus product, already limited due to unfavorable natural and climatic conditions, was sharply reduced, and the possibilities for progressive development were extremely difficult.

The severe negative consequences of the Mongol invasion affected different regions of Ancient Rus' with unequal force. The princes of North-Eastern Rus' had to, like the sons-in-law of other ancient Russian lands, go to the Horde for labels and pay a heavy “exit”. They also lost tribute from the tribes of the Middle Volga region, which were now subordinated to the power of the khan in Sarai. Nevertheless, it was possible to preserve the traditional forms of social structure and the traditional organization of the Vladimir Great Reign, when the prince - the holder of the label for the Great Reign - took possession of the city of Vladimir with the surrounding territories, enjoyed a kind of honorary seniority among the Russian princes and could convene the princes to congresses to decide issues concerning the entire “land” (for example, to discuss how the khan’s orders should be carried out). This state of affairs was greatly facilitated by the fact that in the north of Rus' in the forest zone of Eastern Europe there were no territories suitable for nomadic cattle breeding, that is, there were no conditions for the regime of permanent occupation of these lands by the Mongols.

A different situation developed in the south of Rus', in the forest-steppe zone of Eastern Europe. In some territories, such as in the Southern Bug basin, the Horde nomads themselves were located, in other territories the Horde established their direct, immediate control. Thus, according to the Ipatiev Chronicle, the Bolokhov land in the southern part of the Galicia-Volyn principality was not devastated during the invasion - “they were left to the Tatars to weed out wheat and millet.” When Plano Carpini traveled to the Horde in 1245, he noticed that the city of Kanev, located on the Dnieper below Kyiv, was “under the direct rule of the Tatars.” The Tatars met Daniil Galitsky, who was traveling to the Horde at the same time, even near Pereyaslavl. Soon after the Mongol invasion, the princely tables ceased to exist in Kiev and Pereyaslavl in Russia, and in the Chernigov land Roman, the son of Michael killed in the Horde, moved the capital of the principality from Chernigov to Bryansk, to the region of the famous Bryansk forests, and the episcopal see also moved there. The sons of Mikhail, judging by their names in the genealogical tradition, moved to the towns along the Upper Oka in the northern part of the Chernigov land that became their fiefs. The Metropolitan, who in previous years rarely left Kiev, now begins to spend more and more time in the north of Rus', and in 1300, when, according to the chronicle, “all of Kiev fled,” that is, became an empty city, Metropolitan Maxim, “not tolerating the Tatar violence”, moved the metropolitan residence to Vladimir on Klyazma.

All these specific facts were an external reflection of deeper, hidden processes - the migration of the population from the forest-steppe zone - the area of direct presence of the Horde - to forest areas more distant from their nomads, less accessible to them due to terrain conditions.

The difficulties that the ancient Russian lands faced after the Mongol-Tatar invasion turned out to be all the more difficult to overcome because at the same time they were subjected to hostile actions from other external forces.

Lithuania and Russian lands in the 13th century. The process of formation of the early feudal Lithuanian state, which began in the southern Baltic, was already accompanied in the last decades of the 12th - early 13th centuries. a sharp increase in Lithuanian raids on neighboring lands. The time has passed when, as stated in “The Tale of the Destruction of the Russian Land,” “Lithuania did not emerge from the swamps into the light.” Lithuanian squads not only systematically devastated the Polotsk and Smolensk lands neighboring Lithuania. In the second decade of the 13th century. Lithuanian squads had already carried out raids on Volyn, Chernigov and Novgorod lands. Under 1225, the Vladimir chronicler wrote: “Lithuania fought the Novgorod volost and captured many, many evil Christians and did a lot of evil, fighting near Novagorod and near Toropcha and Smolensk and to Poltesk, the battle was great, like there was no such thing from the beginning of the world.” . In the years following the Mongol invasion, these raids intensified even more. Plano Carpini, who was traveling from Volhynia to Kiev in 1245, wrote: “We were constantly traveling in mortal danger because of the Lithuanians, who often raided the lands of Russia, and since most of the people of Russia were killed by the Tatars and taken into captivity, then they were therefore by no means able to offer them strong resistance.” In the middle of the 13th century, when the Lithuanian tribes united into one state led by Mindaugas, the transition began from raids to capture booty and prisoners to the occupation of Russian cities by Lithuanian squads. By the end of the 40s. XIII century Mindovg's power extended to the territory of modern Western Belarus with cities such as Novogrudok and Grodno. Since the 60s XIII century Princes dependent on Lithuania were also established in the main center on the territory of modern Eastern Belarus - in Polotsk.

Crusaders in the Baltics. The offensive of German and Swedish knights on Russian lands. By the time of the Mongol invasion, a wave of external expansion had reached the borders of the ancient Russian lands, which began in northern Europe in the second half of the 12th century. This was the expansion of the knighthood of Northern Germany, Denmark and Sweden in the form of crusades into the lands of the "pagan" peoples on the southern and eastern coasts of the Baltic Sea. This expansion was supported by the merchants of the port cities of Northern Germany, who hoped to bring under their control the trade routes along the Baltic Sea that connected the East and West of Europe. If the ancient Russian principalities were content with collecting tribute from subordinate tribes without interfering in their internal life, then the crusaders set as their goal their transformation into dependent peasants. In the occupied territories, stone fortresses were systematically built (Riga, Tallinn - literally translated as “Danish city”, etc.), which became strongholds of the new government. At the same time, local residents were forcibly forced to accept the Catholic faith. The most effective weapon of expansion in this area was the knightly orders. Uniting in their ranks knights who had taken monastic vows, the orders were able to create a strong, well-organized and well-armed army, subordinate to a single leadership, which, as a rule, prevailed over the scattered tribal militias.

The first campaigns of the Swedish crusaders on the territory of modern Finland began already in the middle of the 12th century. Initially, their object was a territory remote from the Russian borders in the southwestern part of the country, but, having gained a foothold in these lands, the Swedish knights from the 20s. XIII century began to try to subjugate the Em tribe, which lay in the zone of Novgorod influence.

At the very end of the 12th century. German crusaders landed on the Western Dvina. In 1201, at its mouth they founded their stronghold - the city of Riga. The main military force of the Crusaders in the Baltics was the Order of the Swordsmen, established in 1202 (later called the Livonian Order). Prince Vladimir of Polotsk, who ruled a land devastated by Lithuanian raids and disintegrated into a number of small principalities, was forced in 1213 to make peace with the crusaders, according to which he renounced claims to the lands of tribes that had previously paid tribute to Polotsk. In 1223, weakened by the fight against the knights and Lithuanians, Polotsk was captured by Smolensk. The crusaders began to invade the Estonian lands. In 1224, after a brutal assault, Yuriev fell, and Izborsk was under threat. This is already by the middle of the second decade of the 13th century. led to a conflict between the crusaders and Novgorod. The military operations that took place simultaneously in the territories of Estonia and Finland had one common feature. The Novgorod state (in particular, in those years when Yaroslav, the younger brother of the Grand Duke of Vladimir Yuri Vsevolodovich, reigned in Novgorod) repeatedly undertook military campaigns to restore its positions, and in 1236 reached peace with the Swordsmen. But the latter soon attracted the Teutonic Order from Palestine to expansion. Novgorod troops repeatedly won victories in the open field; on the territory of Estonia they could rely on the support of local tribes who were looking for support in Novgorod against the crusaders. However, the results of these victories could not be consolidated. Unlike the Crusaders, the Novgorodians did not create a network of fortified strongholds in the territories they controlled, and neither the Estonians nor the Novgorodians had the necessary equipment to capture and destroy knightly castles. In addition, after the German crusaders, Denmark also invaded the zone of Novgorod influence. The troops of the Danish king occupied the northern part of Estonia, establishing their stronghold here in the city of Revel (modern Tallinn) (1219).

By the middle of the 13th century. Novgorod zone of influence in the Baltic states and Finland ceased to exist. The Novgorod boyars and the city community lost the tribute that came to Novgorod from the tribes living there. The German merchants, having gained strongholds on trade routes, ousted the Novgorod merchants from the Baltic Sea.

The terrible devastation of Russian lands during the Mongol invasion pushed Novgorod's western neighbors to attack Novgorod territory. In the summer of 1240, a large Swedish army landed at the mouth of the Neva. The Swedish military leaders hoped, by building a fortress at the mouth of the Neva, to bring under their control the most important waterway leading from the Baltic Sea to the Novgorod lands, and to subordinate to their power the land located around the Izhora tribe, allied to Novgorod. This plan was thwarted thanks to the quick and decisive actions of the son of the Grand Duke of Vladimir Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, Alexander, who was reigning in Novgorod. Having quickly set out on a campaign with small military forces, on July 15 he managed to suddenly attack the Swedish army that was resting and defeated it. The Swedes fled, loading the dead onto their ships. A vivid description of the battle was preserved in his “Life”, created after the death of Alexander, in the compilation of which the stories of the soldiers who took part in the battle were used. One of the warriors, Gavrila Aleksich, pursuing the Swedes, burst onto the Swedish ship on horseback. One of the “young men” named Sava, having made his way to the “great golden-domed” tent of the Swedish military leaders in the midst of the battle, brought it down, causing the Russian army to rejoice. Alexander himself fought with the leader of the Swedes and “put a seal on his face with his sharp spear.” For this victory, Alexander Yaroslavich was nicknamed Nevsky.

The actions of the German crusaders turned out to be even more dangerous for the Novgorod state. In the summer of the same 1240, they managed to capture the Pskov suburb of Izborsk and defeated the Pskov army that opposed them. Later, due to the betrayal of some of the Pskov boyars, they occupied Pskov. Then the crusaders occupied the land of the Vodi tribe, allied to Novgorod, and set up a fortress there. Separate detachments of crusaders devastated villages 30 versts from Novgorod. The following year, 1241, Alexander Yaroslavin liberated the lands they had captured from the crusaders. Alexander Yaroslavich, having strengthened his Novgorod army with regiments sent by his father, undertook a campaign against the lands of Chud, subject to the Order, and met the Order’s troops on the ice of Lake Peipsi on Uzmen “at the Raven’s Stone.” The German army was a powerful force. At the beginning of the battle, it “punched a pig through the regiment” of the Novgorodians, but the “great battle” ended in victory for the Russian army. In the battle that took place on April 5, 1242, the heavily armed knightly army was defeated. Russian soldiers pursued the fleeing 7 versts to the western shore of Lake Peipsi. After this, peace was concluded, according to which the Order renounced all previously captured Novgorod lands. The attacks on Novgorod ended in complete failure, but the western borders of the Novgorod state had strong hostile neighbors, and the Novgorodians had to be constantly prepared to repel attacks from them.

Everything that happened contributed to a change in the Russian people’s understanding of the outside world; it began to be perceived primarily as an alien, hostile force from which danger constantly emanates. Hence the desire to isolate yourself from this world and limit your contacts with it. Antagonism of Ancient Rus' with the nomadic world by the 13th century. was traditional, but the disasters of the Mongol invasion contributed to its further aggravation. It was probably at that time that the struggle of the heroes for the liberation of Rus' from the Horde yoke became one of the main themes of the Russian heroic epic. What became new was acute antagonism with the Western, “Latin” world, which was not typical for earlier centuries, which for ancient Russian society was a natural reaction to hostile actions on the part of its Western neighbors. Since that time, various ties with the countries of Western Europe have been sharply reduced, being limited primarily to the sphere of trade relations.

One of the important negative consequences of changes in the situation of ancient Russian lands in the 13th century. there was a weakening, or even a severing of ties between the individual lands of Ancient Rus'. Comparison of chronicle news of the first and second half of the 13th century. clearly shows that the chronicle monuments created in the Rostov-Suzdal land, in Novgorod, in the Galicia-Volyn principality in the first half of the 13th century. contain messages about events that took place in different lands of Ancient Rus', and in the second half of the 13th century. the chronicler's horizons are limited to the framework of his reign. All this created the prerequisites for the special, independent development of different parts of Ancient Rus', but in the 13th century. that was a long way off. All Eastern Slavs, despite the weakening of ties between them, continued to live in a single sociocultural space.

The current situation created great difficulties for the Novgorod boyars, who based their policy on taking advantage of the rivalry between different centers of Ancient Rus'. The possibilities for such maneuvering were sharply reduced with the desolation of the Chernigov land and the involvement of Smolensk in the fight against the Lithuanians. At the same time, in conditions of serious conflicts with its western neighbors, Novgorod needed external support. Gradually during the second half of the 13th century. A tradition developed according to which the chief of the princes of North-Eastern Rus', the Grand Duke of Vladimir, became the Novgorod prince, who sent his governors to Novgorod. For the formation of a unified Russian state in the historical perspective, such an establishment of a permanent connection between North-Eastern Russia and Novgorod was of great importance.

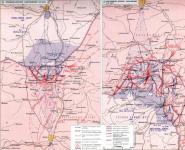

Russian lands and the Golden Horde in the second half of the 13th century. If for Novgorod in the 13th century. Since relations with their western neighbors were especially important, the state of affairs in the principalities of North-Eastern Rus' depended entirely on their relations with the Horde. Not all ancient Russian princes were ready to put up with the establishment of Horde domination over the Russian lands. The most powerful of the rulers of southern Rus', the Galician-Volyn prince Daniil Romanovich, hatched a plan to liberate the Horde from power with the support of the states of Western Europe, primarily his neighbors - Poland and Hungary. The papal throne, to which Daniel promised to submit, was supposed to facilitate the receipt of help. Both the Grand Duke of Vladimir Andrei Yaroslavich and his younger brother Yaroslav, who was sitting in Tver, were involved in the implementation of these plans. Let us note that by the will of the widow of the Great Khan Gukzha in 1249, the sons of the poisoned Yaroslav Vsevolodovich received labels for the reign: Andrei - for Vladimir, and Alexander, who gained fame in battles - for Kiev. In 1250, Daniel’s union with the Vladimir prince was sealed by marriage: Andrei married the daughter of Prince Daniel. In 1252, counting on receiving help quickly, Daniel refused to obey the Horde and began military operations. When the hordes of Kuremsa, wandering in the Dnieper region, moved to the Galicia-Volyn region, Daniel went to war against him and recaptured a number of cities from the Mongols. Residents of Vladimir Volynsky and Lutsk independently repulsed Kuremsa’s detachments. Andrei and Yaroslav Yaroslavich did the same when they opposed the Tatars in the same year. Then Khan Batu sent an army led by commander Nevryu to North-Eastern Rus'. However, the princes did not dare to join the battle and fled. The country was again devastated. The Horde army took with it a “countless,” as the chronicler put it, number of prisoners and livestock. The most influential of the princes of North-Eastern Rus', Alexander Nevsky, did not take part in such plans, considering them unrealistic. The course of events confirmed the correctness of his considerations. Daniil Romanovich fought with the Horde commanders for several years, but never received any help from his western neighbors. In 1258, he was forced to submit to the power of the Horde and raze all the main fortresses on the territory of his principality. His army was forced to take part in campaigns organized by the Horde against Lithuania and Poland.

Alexander Nevsky, who took the Vladimir grand-ducal throne in 1252, pursued a policy of strict fulfillment of obligations to the Horde. In 1259, he made a special visit to Novgorod to convince the city's residents to agree to conduct a census and pay tribute to the Horde. Thus, Alexander Nevsky hoped to avoid repeated punitive campaigns and create minimal conditions for the revival of life in a devastated country. Thanks to his personal authority, he was able to subjugate other princes of North-Eastern Rus', who went on campaigns on his orders, in particular against the German knights. However, soon after his death, the Great Reign of Vladimir was engulfed in prolonged unrest.

With all the cruel and predatory nature of the orders established by the Horde, one could have expected in these conditions at least an end to the strife, since all the princely tables were now occupied by the decision of the khan, an action against which threatened with the most severe consequences. The cessation of strife could have contributed to the restoration, at least gradually and slowly, of economic and social life on the territory of the Great Reign of Vladimir, but it turned out differently. In the early 80s. XIII century A split occurred in the Golden Horde state. Its western part separated from the Horde - the ulus of one of Batu’s distant relatives - Nogai, which occupied lands from the Lower Danube to the Dnieper. Nogai sought to place his proteges on the khan's throne, which caused a hostile reaction from the nobility sitting in Sarai. The establishment of dual power in the Horde contributed to the outbreak of the struggle for the Vladimir grand-ducal table between the sons of Alexander Nevsky - Dmitry and Andrei. In the 80s XIII century The princes of North-Eastern Rus' split into two hostile alliances, each of which turned to “their” khan for support and brought Tatar troops to Rus'. If Dmitry Alexandrovich and his allies Mikhail Tverskoy and Daniil Moskovsky, the youngest son of Alexander Nevsky, were associated with Nogai, then Andrei Alexandrovich and the Rostov princes and Fyodor Yaroslavsky who supported him sought help from the khans sitting in Sarai. The princely strife that ravaged the country in the last decades of the 13th century. were accompanied by constant invasions of the Horde. The largest of them was the so-called Dudenev's army - an army led by Tsarevich Tudan, the brother of Khan Tokhta, who was sitting on the Volga, who was supposed to bring Dmitry Alexandrovich and his allies to obedience. Just as during Batu’s invasion, 14 cities were devastated, including Moscow, Suzdal, Vladimir, and Pereyaslavl. Tudan did not dare to attack Tver, where Nogai’s troops were located. The death of Dmitry Alexandrovich did not put an end to the strife. Now

Daniel of Moscow in 1296 made claims to the grand-ducal table and sent his son Ivan as governor to Novgorod. In response to this, Andrei Alexandrovich brought a new army from the Volga Horde led by Nevryuy. It was not until 1297 that peace was concluded between the rival factions. Thus, by the end of the 13th century. The severe consequences of the Mongol invasion were not only not overcome, but were also aggravated by new disasters.

MONGOL-TATAR INVASION

Formation of the Mongolian state. At the beginning of the 13th century. In Central Asia, the Mongolian state was formed in the territory from Lake Baikal and the upper reaches of the Yenisei and Irtysh in the north to the southern regions of the Gobi Desert and the Great Wall of China. After the name of one of the tribes that roamed near Lake Buirnur in Mongolia, these peoples were also called Tatars. Subsequently, all the nomadic peoples with whom Rus' fought began to be called Mongol-Tatars.

The main occupation of the Mongols was extensive nomadic cattle breeding, and in the north and in the taiga regions - hunting. In the 12th century. The Mongols experienced a collapse of primitive communal relations. From among ordinary community herders, who were called karachu - black people, noyons (princes) - nobility - emerged; Having squads of nukers (warriors), she seized pastures for livestock and part of the young animals. The Noyons also had slaves. The rights of noyons were determined by “Yasa” - a collection of teachings and instructions.

In 1206, a congress of the Mongolian nobility took place on the Onon River - kurultai (Khural), at which one of the noyons was elected leader of the Mongolian tribes: Temujin, who received the name Genghis Khan - “great khan”, “sent by God” (1206-1227). Having defeated his opponents, he began to rule the country through his relatives and local nobility.

Mongol army. The Mongols had a well-organized army that maintained family ties. The army was divided into tens, hundreds, thousands. Ten thousand Mongol warriors were called "darkness" ("tumen").

Tumens were not only military, but also administrative units.

The main striking force of the Mongols was the cavalry. Each warrior had two or three bows, several quivers with arrows, an ax, a rope lasso, and was good with a saber. The warrior's horse was covered with skins, which protected it from arrows and enemy weapons. The head, neck and chest of the Mongol warrior were covered from enemy arrows and spears by an iron or copper helmet and leather armor. The Mongol cavalry had high mobility. On their short, shaggy-maned, hardy horses, they could travel up to 80 km per day, and with convoys, battering rams and flamethrowers - up to 10 km. Like other peoples, going through the stage of state formation, the Mongols were distinguished by their strength and solidity. Hence the interest in expanding pastures and organizing predatory campaigns against neighboring agricultural peoples, who were at a much higher level of development, although they were experiencing a period of fragmentation. This greatly facilitated the implementation of the Mongol-Tatars’ plans of conquest.

The defeat of Central Asia. The Mongols began their campaigns by conquering the lands of their neighbors - the Buryats, Evenks, Yakuts, Uighurs, and Yenisei Kyrgyz (by 1211). They then invaded China and took Beijing in 1215. Three years later, Korea was conquered. Having defeated China (finally conquered in 1279), the Mongols significantly strengthened their military potential. Flamethrowers, battering rams, stone-throwers, and vehicles were adopted.

In the summer of 1219, an almost 200,000-strong Mongol army led by Genghis Khan began the conquest of Central Asia. The ruler of Khorezm (a country at the mouth of the Amu Darya), Shah Mohammed, did not accept a general battle, dispersing his forces among the cities. Having suppressed the stubborn resistance of the population, the invaders stormed Otrar, Khojent, Merv, Bukhara, Urgench and other cities. The ruler of Samarkand, despite the demand of the people to defend himself, surrendered the city. Muhammad himself fled to Iran, where he soon died.

The rich, flourishing agricultural regions of Semirechye (Central Asia) turned into pastures. Irrigation systems built over centuries were destroyed. The Mongols introduced a regime of cruel exactions, artisans were taken into captivity. As a result of the Mongol conquest of Central Asia, nomadic tribes began to populate its territory. Sedentary agriculture was replaced by extensive nomadic cattle breeding, which slowed down the further development of Central Asia.

Invasion of Iran and Transcaucasia. The main force of the Mongols returned from Central Asia to Mongolia with looted booty. An army of 30,000 under the command of the best Mongol military commanders Jebe and Subedei set off on a long-distance reconnaissance campaign through Iran and Transcaucasia, to the West. Having defeated the united Armenian-Georgian troops and caused enormous damage to the economy of Transcaucasia, the invaders, however, were forced to leave the territory of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, as they encountered strong resistance from the population. Past Derbent, where there was a passage along the shores of the Caspian Sea, the Mongol troops entered the steppes of the North Caucasus. Here they defeated the Alans (Ossetians) and Cumans, after which they ravaged the city of Sudak (Surozh) in the Crimea. The Polovtsians, led by Khan Kotyan, the father-in-law of the Galician prince Mstislav the Udal, turned to the Russian princes for help.

Battle of the Kalka River. On May 31, 1223, the Mongols defeated the allied forces of the Polovtsian and Russian princes in the Azov steppes on the Kalka River. This was the last major joint military action of the Russian princes on the eve of Batu's invasion. However, the powerful Russian prince Yuri Vsevolodovich of Vladimir-Suzdal, son of Vsevolod the Big Nest, did not participate in the campaign.

Princely feuds also affected during the battle on Kalka. The Kiev prince Mstislav Romanovich, having strengthened himself with his army on the hill, did not take part in the battle. Regiments of Russian soldiers and Polovtsy, having crossed Kalka, struck the advanced detachments of the Mongol-Tatars, who retreated. The Russian and Polovtsian regiments became carried away in pursuit. The main Mongol forces that approached took the pursuing Russian and Polovtsian warriors in a pincer movement and destroyed them.

The Mongols besieged the hill where the Kiev prince fortified himself. On the third day of the siege, Mstislav Romanovich believed the enemy’s promise to release the Russians with honor in case of voluntary surrender and laid down his arms. He and his warriors were brutally killed by the Mongols. The Mongols reached the Dnieper, but did not dare to enter the borders of Rus'. Rus' has never known a defeat equal to the Battle of the Kalka River. Only a tenth of the army returned from the Azov steppes to Rus'. In honor of their victory, the Mongols held a “feast on bones.” The captured princes were crushed under the boards on which the victors sat and feasted.

Preparations for a campaign against Rus'. Returning to the steppes, the Mongols made an unsuccessful attempt to capture Volga Bulgaria. Reconnaissance in force showed that it was possible to wage aggressive wars with Russia and its neighbors only by organizing an all-Mongol campaign. The head of this campaign was the grandson of Genghis Khan, Batu (1227-1255), who received from his grandfather all the territories in the west, “where the foot of a Mongol horse has set foot.” Subedei, who knew the theater of future military operations well, became his main military adviser.

In 1235, at a khural in the capital of Mongolia, Karakorum, a decision was made on an all-Mongol campaign to the West. In 1236, the Mongols captured Volga Bulgaria, and in 1237 they subjugated the nomadic peoples of the Steppe. In the fall of 1237, the main forces of the Mongols, having crossed the Volga, concentrated on the Voronezh River, aiming at Russian lands. In Rus' they knew about the impending menacing danger, but princely strife prevented the vultures from uniting to repel a strong and treacherous enemy. There was no unified command. City fortifications were erected for defense against neighboring Russian principalities, and not against steppe nomads. The princely cavalry squads were not inferior to the Mongol noyons and nukers in terms of armament and fighting qualities. But the bulk of the Russian army was the militia - urban and rural warriors, inferior to the Mongols in weapons and combat skills. Hence the defensive tactics, designed to deplete the enemy’s forces.

Defense of Ryazan. In 1237, Ryazan was the first of the Russian lands to be attacked by invaders. The princes of Vladimir and Chernigov refused to help Ryazan. The Mongols besieged Ryazan and sent envoys who demanded submission and one tenth of "everything." The courageous response of the Ryazan residents followed: “If we are all gone, then everything will be yours.” On the sixth day of the siege, the city was taken, the princely family and surviving residents were killed. Ryazan was no longer revived in its old place (modern Ryazan is a new city, located 60 km from old Ryazan; it used to be called Pereyaslavl Ryazansky).

Conquest of North-Eastern Rus'. In January 1238, the Mongols moved along the Oka River to the Vladimir-Suzdal land. The battle with the Vladimir-Suzdal army took place near the city of Kolomna, on the border of the Ryazan and Vladimir-Suzdal lands. In this battle, the Vladimir army died, which actually predetermined the fate of North-Eastern Rus'.

The population of Moscow, led by governor Philip Nyanka, offered strong resistance to the enemy for 5 days. After being captured by the Mongols, Moscow was burned and its inhabitants were killed.

On February 4, 1238, Batu besieged Vladimir. His troops covered the distance from Kolomna to Vladimir (300 km) in a month. On the fourth day of the siege, the invaders broke into the city through gaps in the fortress wall next to the Golden Gate. The princely family and the remnants of the troops locked themselves in the Assumption Cathedral. The Mongols surrounded the cathedral with trees and set it on fire.

After the capture of Vladimir, the Mongols split into separate detachments and destroyed the cities of North-Eastern Rus'. Prince Yuri Vsevolodovich, even before the invaders approached Vladimir, went to the north of his land to gather military forces. The hastily assembled regiments in 1238 were defeated on the Sit River (the right tributary of the Mologa River), and Prince Yuri Vsevolodovich himself died in the battle.

The Mongol hordes moved to the north-west of Rus'. Everywhere they met stubborn resistance from the Russians. For two weeks, for example, the distant suburb of Novgorod, Torzhok, defended itself. Northwestern Rus' was saved from defeat, although it paid tribute.

Having reached the stone Ignach-cross - an ancient sign-sign on the Valdai watershed (one hundred kilometers from Novgorod), the Mongols retreated south, to the steppes, to recover losses and give rest to tired troops. The withdrawal was in the nature of a "round-up". Divided into separate detachments, the invaders “combed” Russian cities. Smolensk managed to fight back, other centers were defeated. During the “raid”, Kozelsk offered the greatest resistance to the Mongols, holding out for seven weeks. The Mongols called Kozelsk an “evil city.”

Capture of Kyiv. In the spring of 1239, Batu defeated Southern Rus' (Pereyaslavl South), and in the fall - the Principality of Chernigov. In the autumn of the following 1240, Mongol troops, having crossed the Dnieper, besieged Kyiv. After a long defense, led by Voivode Dmitry, the Tatars defeated Kyiv. The next year, 1241, the Galicia-Volyn principality was attacked.

Batu's campaign against Europe. After the defeat of Rus', the Mongol hordes moved towards Europe. Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and the Balkan countries were devastated. The Mongols reached the borders of the German Empire and reached the Adriatic Sea. However, at the end of 1242 they suffered a series of setbacks in the Czech Republic and Hungary. From distant Karakorum came news of the death of the great Khan Ogedei, the son of Genghis Khan. This was a convenient excuse to stop the difficult hike. Batu turned his troops back to the east.

The decisive world-historical role in saving European civilization from the Mongol hordes was played by the heroic struggle against them by the Russians and other peoples of our country, who took the first blow of the invaders. In fierce battles in Rus', the best part of the Mongol army died. The Mongols lost their offensive power. They could not help but take into account the liberation struggle that unfolded in the rear of their troops. A.S. Pushkin rightly wrote: “Russia had a great destiny: its vast plains absorbed the power of the Mongols and stopped their invasion at the very edge of Europe... the emerging enlightenment was saved by torn Russia.”

The fight against the aggression of the crusaders. The coast from the Vistula to the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea was inhabited by Slavic, Baltic (Lithuanian and Latvian) and Finno-Ugric (Estonians, Karelians, etc.) tribes. At the end of the XII - beginning of the XIII centuries. The Baltic peoples are completing the process of decomposition of the primitive communal system and the formation of an early class society and statehood. These processes occurred most intensively among the Lithuanian tribes. The Russian lands (Novgorod and Polotsk) had a significant influence on their western neighbors, who did not yet have their own developed statehood and church institutions (the peoples of the Baltic states were pagans).

The attack on Russian lands was part of the predatory doctrine of the German knighthood “Drang nach Osten” (onset to the East). In the 12th century. it began to seize lands belonging to the Slavs beyond the Oder and in the Baltic Pomerania. At the same time, an attack was carried out on the lands of the Baltic peoples. The Crusaders' invasion of the Baltic lands and North-Western Rus' was sanctioned by the Pope and German Emperor Frederick II. German, Danish, Norwegian knights and troops from other northern European countries also took part in the crusade.

Knightly orders. To conquer the lands of the Estonians and Latvians, the knightly Order of the Swordsmen was created in 1202 from the crusading detachments defeated in Asia Minor. Knights wore clothes with the image of a sword and cross. They pursued an aggressive policy under the slogan of Christianization: “Whoever does not want to be baptized must die.” Back in 1201, the knights landed at the mouth of the Western Dvina (Daugava) River and founded the city of Riga on the site of a Latvian settlement as a stronghold for the subjugation of the Baltic lands. In 1219, Danish knights captured part of the Baltic coast, founding the city of Revel (Tallinn) on the site of an Estonian settlement.

In 1224, the crusaders took Yuryev (Tartu). To conquer the lands of Lithuania (Prussians) and southern Russian lands in 1226, the knights of the Teutonic Order, founded in 1198 in Syria during the Crusades, arrived. Knights - members of the order wore white cloaks with a black cross on the left shoulder. In 1234, the Swordsmen were defeated by the Novgorod-Suzdal troops, and two years later - by the Lithuanians and Semigallians. This forced the crusaders to join forces. In 1237, the Swordsmen united with the Teutons, forming a branch of the Teutonic Order - the Livonian Order, named after the territory inhabited by the Livonian tribe, which was captured by the Crusaders.

Battle of the Neva. The offensive of the knights especially intensified due to the weakening of Rus', which was bleeding in the fight against the Mongol conquerors.

In July 1240, Swedish feudal lords tried to take advantage of the difficult situation in Rus'. The Swedish fleet with troops on board entered the mouth of the Neva. Having climbed the Neva until the Izhora River flows into it, the knightly cavalry landed on the shore. The Swedes wanted to capture the city of Staraya Ladoga, and then Novgorod.

Prince Alexander Yaroslavich, who was 20 years old at the time, and his squad quickly rushed to the landing site. “We are few,” he addressed his soldiers, “but God is not in power, but in truth.” Hiddenly approaching the Swedes' camp, Alexander and his warriors struck at them, and a small militia led by Novgorodian Misha cut off the Swedes' path along which they could escape to their ships.

The Russian people nicknamed Alexander Yaroslavich Nevsky for his victory on the Neva. The significance of this victory is that it stopped Swedish aggression to the east for a long time and retained access to the Baltic coast for Russia. (Peter I, emphasizing Russia’s right to the Baltic coast, founded the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in the new capital on the site of the battle.)

Battle on the Ice. In the summer of the same 1240, the Livonian Order, as well as Danish and German knights, attacked Rus' and captured the city of Izborsk. Soon, due to the betrayal of the mayor Tverdila and part of the boyars, Pskov was taken (1241). Strife and strife led to the fact that Novgorod did not help its neighbors. And the struggle between the boyars and the prince in Novgorod itself ended with the expulsion of Alexander Nevsky from the city. Under these conditions, individual detachments of the crusaders found themselves 30 km from the walls of Novgorod. At the request of the veche, Alexander Nevsky returned to the city.

Together with his squad, Alexander liberated Pskov, Izborsk and other captured cities with a sudden blow. Having received news that the main forces of the Order were coming towards him, Alexander Nevsky blocked the path of the knights, placing his troops on the ice of Lake Peipsi. The Russian prince showed himself to be an outstanding commander. The chronicler wrote about him: “We win everywhere, but we won’t win at all.” Alexander placed his troops under the cover of a steep bank on the ice of the lake, eliminating the possibility of enemy reconnaissance of his forces and depriving the enemy of freedom of maneuver. Considering the formation of the knights in a “pig” (in the form of a trapezoid with a sharp wedge in front, which was made up of heavily armed cavalry), Alexander Nevsky positioned his regiments in the form of a triangle, with the tip resting on the shore. Before the battle, some of the Russian soldiers were equipped with special hooks to pull knights off their horses.

On April 5, 1242, a battle took place on the ice of Lake Peipsi, which became known as the Battle of the Ice. The knight's wedge pierced the center of the Russian position and buried itself in the shore. The flank attacks of the Russian regiments decided the outcome of the battle: like pincers, they crushed the knightly “pig”. The knights, unable to withstand the blow, fled in panic. The Novgorodians drove them seven miles across the ice, which by spring had become weak in many places and was collapsing under the heavily armed soldiers. The Russians pursued the enemy, “flogged, rushing after him as if through the air,” the chronicler wrote. According to the Novgorod Chronicle, “400 Germans died in the battle, and 50 were taken prisoner” (German chronicles estimate the number of dead at 25 knights). The captured knights were marched in disgrace through the streets of Mister Veliky Novgorod.

The significance of this victory is that the military power of the Livonian Order was weakened. The response to the Battle of the Ice was the growth of the liberation struggle in the Baltic states. However, relying on the help of the Roman Catholic Church, the knights at the end of the 13th century. captured a significant part of the Baltic lands.

Russian lands under the rule of the Golden Horde. In the middle of the 13th century. one of Genghis Khan's grandsons, Khubulai, moved his headquarters to Beijing, founding the Yuan dynasty. The rest of the Mongol Empire was nominally subordinate to the Great Khan in Karakorum. One of Genghis Khan's sons, Chagatai (Jaghatai), received the lands of most of Central Asia, and Genghis Khan's grandson Zulagu owned the territory of Iran, part of Western and Central Asia and Transcaucasia. This ulus, allocated in 1265, is called the Hulaguid state after the name of the dynasty. Another grandson of Genghis Khan from his eldest son Jochi, Batu, founded the state of the Golden Horde.

Golden Horde. The Golden Horde covered a vast territory from the Danube to the Irtysh (Crimea, the North Caucasus, part of the lands of Rus' located in the steppe, the former lands of Volga Bulgaria and nomadic peoples, Western Siberia and part of Central Asia). The capital of the Golden Horde was the city of Sarai, located in the lower reaches of the Volga (sarai translated into Russian means palace). It was a state consisting of semi-independent uluses, united under the rule of the khan. They were ruled by Batu's brothers and the local aristocracy.

The role of a kind of aristocratic council was played by the “Divan”, where military and financial issues were resolved. Finding themselves surrounded by a Turkic-speaking population, the Mongols adopted the Turkic language. The local Turkic-speaking ethnic group assimilated the Mongol newcomers. A new people was formed - the Tatars. In the first decades of the Golden Horde's existence, its religion was paganism.

The Golden Horde was one of the largest states of its time. At the beginning of the 14th century, she could field an army of 300,000. The heyday of the Golden Horde occurred during the reign of Khan Uzbek (1312-1342). During this era (1312), Islam became the state religion of the Golden Horde. Then, just like other medieval states, the Horde experienced a period of fragmentation. Already in the 14th century. The Central Asian possessions of the Golden Horde separated, and in the 15th century. The Kazan (1438), Crimean (1443), Astrakhan (mid-15th century) and Siberian (late 15th century) khanates stood out.

Russian lands and the Golden Horde. The Russian lands devastated by the Mongols were forced to recognize vassal dependence on the Golden Horde. The ongoing struggle waged by the Russian people against the invaders forced the Mongol-Tatars to abandon the creation of their own administrative authorities in Rus'. Rus' retained its statehood. This was facilitated by the presence in Rus' of its own administration and church organization. In addition, the lands of Rus' were unsuitable for nomadic cattle breeding, unlike, for example, Central Asia, the Caspian region, and the Black Sea region.

In 1243, the brother of the great Vladimir prince Yuri, who was killed on the Sit River, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich (1238-1246) was called to the khan's headquarters. Yaroslav recognized vassal dependence on the Golden Horde and received a label (letter) for the great reign of Vladimir and a golden tablet ("paizu"), a kind of pass through the Horde territory. Following him, other princes flocked to the Horde.

To control the Russian lands, the institution of Baskakov governors was created - leaders of military detachments of the Mongol-Tatars who monitored the activities of the Russian princes. Denunciation of the Baskaks to the Horde inevitably ended either with the prince being summoned to Sarai (often he was deprived of his label, or even his life), or with a punitive campaign in the rebellious land. Suffice it to say that only in the last quarter of the 13th century. 14 similar campaigns were organized in Russian lands.

Some Russian princes, trying to quickly get rid of vassal dependence on the Horde, took the path of open armed resistance. However, the forces to overthrow the power of the invaders were still not enough. So, for example, in 1252 the regiments of the Vladimir and Galician-Volyn princes were defeated. Alexander Nevsky, from 1252 to 1263 Grand Duke of Vladimir, understood this well. He set a course for the restoration and growth of the economy of the Russian lands. The policy of Alexander Nevsky was also supported by the Russian church, which saw the greatest danger in Catholic expansion, and not in the tolerant rulers of the Golden Horde.

In 1257, the Mongol-Tatars undertook a population census - “recording the number”. Besermen (Muslim merchants) were sent to the cities, and the collection of tribute was given to them. The size of the tribute (“exit”) was very large, only the “tsar’s tribute”, i.e. the tribute in favor of the khan, which was first collected in kind and then in money, amounted to 1,300 kg of silver per year. The constant tribute was supplemented by “requests” - one-time exactions in favor of the khan. In addition, deductions from trade duties, taxes for “feeding” the khan’s officials, etc. went to the khan’s treasury. In total there were 14 types of tribute in favor of the Tatars. Population census in the 50-60s of the 13th century. marked by numerous uprisings of Russian people against the Baskaks, Khan's ambassadors, tribute collectors, and census takers. In 1262, the inhabitants of Rostov, Vladimir, Yaroslavl, Suzdal, and Ustyug dealt with the tribute collectors, the Besermen. This led to the fact that the collection of tribute from the end of the 13th century. was handed over to the Russian princes.

Consequences of the Mongol conquest and the Golden Horde yoke for Rus'. The Mongol invasion and the Golden Horde yoke became one of the reasons for the Russian lands lagging behind the developed countries of Western Europe. Huge damage was caused to the economic, political and cultural development of Rus'. Tens of thousands of people died in battle or were taken into slavery. A significant part of the income in the form of tribute was sent to the Horde.

The old agricultural centers and once-developed territories became desolate and fell into decay. The border of agriculture moved to the north, the southern fertile soils received the name “Wild Field”. Russian cities were subjected to massive devastation and destruction. Many crafts became simplified and sometimes disappeared, which hampered the creation of small-scale production and ultimately delayed economic development.

The Mongol conquest preserved political fragmentation. It weakened the ties between different parts of the state. Traditional political and trade ties with other countries were disrupted. The vector of Russian foreign policy, which ran along the “south-north” line (the fight against the nomadic danger, stable ties with Byzantium and through the Baltic with Europe) radically changed its focus to “west-east”. The pace of cultural development of Russian lands has slowed down.

What you need to know about these topics:

Archaeological, linguistic and written evidence about the Slavs.

Tribal unions of the Eastern Slavs in the VI-IX centuries. Territory. Classes. "The path from the Varangians to the Greeks." Social system. Paganism. Prince and squad. Campaigns against Byzantium.

Internal and external factors that prepared the emergence of statehood among the Eastern Slavs.

Socio-economic development. The formation of feudal relations.

Early feudal monarchy of the Rurikovichs. "Norman theory", its political meaning. Organization of management. Domestic and foreign policy of the first Kyiv princes (Oleg, Igor, Olga, Svyatoslav).

The rise of the Kyiv state under Vladimir I and Yaroslav the Wise. Completion of the unification of the Eastern Slavs around Kyiv. Border defense.

Legends about the spread of Christianity in Rus'. Adoption of Christianity as the state religion. The Russian Church and its role in the life of the Kyiv state. Christianity and paganism.

"Russian Truth". Confirmation of feudal relations. Organization of the ruling class. Princely and boyar patrimony. Feudal-dependent population, its categories. Serfdom. Peasant communities. City.

The struggle between the sons and descendants of Yaroslav the Wise for grand-ducal power. Tendencies towards fragmentation. Lyubech Congress of Princes.

Kievan Rus in the system of international relations of the 11th - early 12th centuries. Polovtsian danger. Princely strife. Vladimir Monomakh. The final collapse of the Kyiv state at the beginning of the 12th century.

Culture of Kievan Rus. Cultural heritage of the Eastern Slavs. Folklore. Epics. The origin of Slavic writing. Cyril and Methodius. The beginning of chronicle writing. "The Tale of Bygone Years". Literature. Education in Kievan Rus. Birch bark letters. Architecture. Painting (frescoes, mosaics, icon painting).

Economic and political reasons for the feudal fragmentation of Rus'.

Feudal land tenure. Urban development. Princely power and boyars. Political system in various Russian lands and principalities.

The largest political entities on the territory of Rus'. Rostov-(Vladimir)-Suzdal, Galicia-Volyn principalities, Novgorod boyar republic. Socio-economic and internal political development of principalities and lands on the eve of the Mongol invasion.

International situation of Russian lands. Political and cultural connections between Russian lands. Feudal strife. Fighting external danger.

The rise of culture in Russian lands in the XII-XIII centuries. The idea of the unity of the Russian land in works of culture. "The Tale of Igor's Campaign."

Formation of the early feudal Mongolian state. Genghis Khan and the unification of the Mongol tribes. The Mongols conquered the lands of neighboring peoples, northeastern China, Korea, and Central Asia. Invasion of Transcaucasia and the southern Russian steppes. Battle of the Kalka River.

Batu's campaigns.

Invasion of North-Eastern Rus'. The defeat of southern and southwestern Rus'. Batu's campaigns in Central Europe. Rus''s struggle for independence and its historical significance.

Aggression of German feudal lords in the Baltic states. Livonian Order. The defeat of the Swedish troops on the Neva and the German knights in the Battle of the Ice. Alexander Nevskiy.

Education of the Golden Horde. Socio-economic and political system. System of management of conquered lands. The struggle of the Russian people against the Golden Horde. Consequences of the Mongol-Tatar invasion and the Golden Horde yoke for the further development of our country.

The inhibitory effect of the Mongol-Tatar conquest on the development of Russian culture. Destruction and destruction of cultural property. Weakening of traditional ties with Byzantium and other Christian countries. Decline of crafts and arts. Oral folk art as a reflection of the struggle against invaders.

- Sakharov A. N., Buganov V. I. History of Russia from ancient times to the end of the 17th century.

How and why did Rus' fall under the rule of the Mongol khans?

We can perceive the historical period we are considering in different ways and evaluate the cause-and-effect relationship of the Mongols’ actions. The facts remain unchanged that the Mongol raid on Rus' took place and that the Russian princes, despite the heroism of the city defenders, were unable or unwilling to see sufficient reasons for eliminating internal disagreements, unification and basic mutual assistance. This did not allow the Mongol army to be repelled and Rus' fell under the rule of the Mongol khans.

What was the main goal of the Mongol conquests?