Cruiser pearl in the First World War. Russian sailors on the edge of the First World War

The history of the appearance of the memorial plaque began with Elena Chekulaeva’s essay “At dawn, in Penang...”, published in the magazine “Around the World” (No. 2/95). It described the death of the Russian cruiser as it appeared “based on materials from yellowed local newspapers” in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur. And, in addition, the essay talked about the monument at the grave of Russian sailors, erected in Soviet times, which was looked after by the shipping company "Hai Tong Shipping", whose director is Mr. Teo, who is also the Honorary Consul of the Russian Federation in Penang.

But the whole point is that the monument was nameless: “To the Russian military sailors of the cruiser “Zhemchug” a grateful homeland” this inscription exhausted all the information about our compatriots who died far from Russia. And remembering recently such popular words: “No one is forgotten, nothing is forgotten,” the magazine “Around the World” decided to find the names of the dead sailors and immortalize them on the Russian monument in Penang. The names of the 88 dead were tracked down in the Russian State Archive of the Navy in St. Petersburg.

The editors of the magazine “Around the World” allocated money for the production of a memorial plaque. Its sketch was made by one of the oldest workers at the Institute of Oceanology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, V. Burenin, and it was realized using computer graphics methods by the artist of the magazine “Around the World” K. Yansitov. A brass board measuring 30x40 cm was ordered from the Moscow company VLAND.

Having received such an unusual order, the head of the company, Vladislav Borisov, informed the editors that, by general agreement of the company’s employees, a plaque in memory of Russian sailors buried far from Russia would be made free of charge. The plaque was consecrated in the Church of St. Nicholas in Khamovniki, after which, together with the correspondents of the magazine “Around the World”, it went to Malaysia.

The representative of Sovfracht in Kuala Lumpur, K. Prostakov, provided great assistance, agreeing on the technical aspects of installing the plaque on the monument and communicating with the city of Penang (Georgetown), located on an island a little over two hundred kilometers from Kuala Lumpur. Russian Ambassador V.Ya. Vorobyov, busy with urgent matters, told correspondents through his assistant that the Honorary Consul of Russia in Penang would take care of the board.

“We will do everything for their memory,” said Mr. Teo Seng Lee in Russian, accepting the memorial plaque. And he kept his promise. In October 1995, as soon as the consequences of the flood, the worst in the last three decades, which the correspondents of our magazine found themselves in Penang, were overcome, the plaque was installed on the monument. The editors of the magazine “Around the World” received photographs depicting the installation of the board.

During the historical search, new information became known about the death of the cruiser Zhemchug, the fate of its commander, as well as the fate of the monument at the grave of Russian sailors. This information, some of which appears in print for the first time, has necessitated the need to historically accurately reconstruct the tragic episode in the history of the Russian fleet and the events that followed, focusing on the Russian monument in Penang.

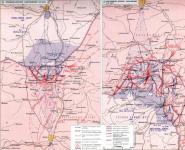

And so, on October 13/26, 1914, "Pearl", the cruiser of the Siberian Flotilla, with the outbreak of hostilities seconded to the allied Anglo-French squadron, returned to the port of Penang, on the island of the same name in the Strait of Malacca, from where at the end of September it went on a campaign in search of the German cruiser Emden. The commander of the “Pearl,” Captain 2nd Rank Baron I.A. Cherkasov, received permission from the English Admiral Jeram, under whose command he was, for a seven-day visit to overhaul the mechanisms and clean the boilers. In connection with the actions of the Emden in this area, the commander of the Russian cruiser was advised to take all precautions while anchored in Penang Bay. But Captain Cherkasov did not take the necessary measures, practically failing to prepare the ship for a possible attack by the Emden. On the evening of October 14/27, he went ashore to his wife, who had been summoned by him to Penang from Vladivostok for the duration of the Pearl’s stay.

Early in the morning of October 15/28, the raider Emden entered Penang, which, as its senior officer Helmuth von Mücke stated in his memoirs, hoped to catch the French armored cruisers Montcalm and Duplex here and attack them while anchored. The Germans used a military trick: they installed a fourth fake pipe made of tarpaulin, so that in poor visibility the Emden could pass for the English cruiser Yarmouth. The French destroyer Musquet, on security duty, fell for this trick and in the pre-dawn twilight allowed the Emden into the bay, even giving the go-ahead with a light signal.

In the bay, among the illuminated “merchants”, the Emden found only one dark silhouette of a warship. Approaching almost close to its stern, the Germans established that it was the Russian cruiser Zhemchug. The same X. von Mücke recalls:

“Peace and silence reigned there. We were so close to him that in the weak light of the dawning day everything that was happening on the Russian cruiser was clearly visible. But neither the watch commander, nor the watchmen, nor the signalmen were visible. From a distance of about one cable length (185.2 maut.), we fired our first mine from the right side apparatus and at the same moment opened fire with the whole side on the bow of the “Pearl”, where most of the crew was sleeping in their bunks. Our mine exploded in the stern of the cruiser. It was as if he was completely shaken by this explosion. The stern was thrown out of the water, and then it began to slowly sink. Only after this did the Russians discover signs of life...

Meanwhile, our artillery maintained furious fire on the “Pearl”... The bow of the cruiser was riddled with bullets in a few minutes. The flames engulfed the entire forecastle. Through the holes in the side the opposite shore was visible.

Finally, on the “Pearl” they gathered their strength and opened fire on us. The guns on it were larger than ours, and Russian shells could cause us great harm. Therefore, the commander decided to fire a second mine. "Emden", passing by "Pearl", turned around and headed towards it again. The second mine was fired from a distance of about two cables. A few seconds later, a terrible explosion was heard under the front bridge of the Russian cruiser. A giant column of gray smoke, steam and water spray rose to a height of about 150 m. Parts of the ship's hull were torn off by the explosion and flew through the air. It was clear that the cruiser had broken in half. The bow part has separated. Then the entire ship was covered in smoke, and when it cleared, the cruiser was no longer visible, only fragments of its mast were sticking out of the water. People swarmed among the wreckage on the water. But Emden had no time for them.”

The French destroyer Musquet rushed towards the departing Emden, having realized his tragic mistake too late. His attack was a gesture of despair; in three salvos he was sunk by the Emden. The wounded lieutenant L.L. Seleznev, who was in the water, saw this: “In place of the Muske, a column of black smoke rose, and it was all over.”

"Pearl" and "Muske" became the last victims of the Emden, the total number of which, not counting these two warships, was 22 ships (including the Russian steamer Ryazan, sailing from Vladivostok to Hong Kong). The German raider, which revealed itself, was already overtaken by the Australian cruiser Sydney off the Cocos Islands on October 27 (November 9) and sunk. By the way, the surviving part of the crew escaped on the shore, and later sailed across the Indian Ocean on a junk, reaching the mainland. Arriving in Germany after their odyssey, the team was received by the Kaiser, who, in commemoration of their merits, added a second surname to everyone - Emden.

As a result of the attack on the Pearl, which was sunk in five minutes, one officer and 80 lower ranks were killed, seven sailors later died from their wounds. The dead officer was midshipman A.K. Sipailo (1891 -1914), who held the position of watch commander on the “Pearl”.

A naval court held in August 1915 in Vladivostok found the commander, captain 2nd rank Ivan Cherkasov, and the senior officer, senior lieutenant Nikolai Kulibin, who replaced the commander who had moved ashore, guilty of the death of the cruiser and people. They were deprived of “ranks and orders and other insignia”, expelled from naval service and “after deprivation of the nobility and all special rights and benefits” they were sent to “correctional prison departments of the civil department”: Cherkasov for 3.5 years, and Kulibin for 1.5 years. By the Supreme Confirmation of the verdict of the Vladivostok Naval Court, both of them were demoted to sailors and sent to the front. Contrary to the assertion of the author of the essay “At Dawn, in Penang...”, the archives contain information and quite complete about their further fate. Sailor 2nd article Baron Ivan Cherkasov fought on the Caucasian front in the Urmia-Van lake flotilla, was awarded the soldier's Cross of St. George and in April 1917 was restored to the rank of captain 2nd rank. It is known that I.A. Cherkasov died in France in March 1942 and was buried in the Sainte-Gensvieve-des-Bois cemetery near Paris. Sailor Nikolai Kulibin fought on the Western Front in a naval brigade, received two Crosses of St. George and was restored to rank in September 1916. Soon he was promoted to captain 2nd rank. He died in hospital in August 1918 from a wound received back in the February days of 1917, when he commanded the destroyer Movable.

In December 1914, the auxiliary cruiser Orel came to Penang to carry out diving work on the sunken Pearl. Most likely, it was the sailors of the "Eagle" who brought and installed a cast-iron cross on the grave of their fallen compatriots, which has survived to this day and is depicted in a photograph by E. Chekulaeva. In any case, it was this cross that was seen in 1938 by the Cossacks of the Platov Don Choir, who were on tour in Penang. But contrary to the stories of the author of the essay “At Dawn, in Penang...” that “throughout all the years until 1975” local residents took care of the grave of Russian sailors, the picture the Cossacks saw was bleak. “There was no one to look after the Russian graves, and they fell into complete desolation and were almost leveled to the surface of the earth. On the iron cross erected on the mass grave, a plate (apparently copper) was once screwed on, but it was stolen,” wrote choir administrator B. Kutsevalov in No. 214 of the Sentinel magazine. The Cossacks decided to allocate funds from the choir fund to put the graves in order. “With these funds, a marble slab was built with the surnames of those buried inscribed according to the cemetery records, the cross was repainted with black paint, several bushes and trees were planted around the graves, and then a wreath of fresh flowers was solemnly laid,” says the author of the article “Platovians on the Road” Boris Kutsevalov.

This article also includes a photograph of a slab with nine surnames written in English, since “it was not easy to decipher Russian surnames.” E. Chekulaeva also mentions the same figure, telling how she finally managed to find these names “in the land administration of the northeastern region” of the state of Penang, where they were preserved, since 9 sailors probably died in the hospital. But for some reason he gives only eight surnames, giving them in his own reverse translation into Russian: Kanuev, Sirotin, Eraskin, Olenikov, Graitasov, Chuvykin, Lieutenant Cherepkov, Shenykin (there is also a ninth surname Bragoff on the plate, not indicated by the author of the essay ). We present seven real Russian names named in the list of lower ranks of the crew of the cruiser “Pearl” who died from wounds in the “Penang Civil Hospital”, and we will talk about the other two below. This list, compiled by the cruiser's ship's doctor, court adviser Smirnov, includes: non-commissioned officer Braga Samuil, sailors Konev Petr, Syrvachev Stepan, Eroshkin Illarion, stokers Olein and kov Kirill, Gryadasov Grigory and driver Chebykin Grigory. Comparing the two lists, one involuntarily doubts whether someone will be able to “find out the surname of a grandfather or great-grandfather” from the first of them.

Special mention should be made about two names from the gravestone erected by the Cossacks, which were included in the list found by E. Chekulaeva in the land administration. Already in the 220th issue of the Sentinel magazine, B. Kutsevalov, according to letters from readers, was forced to place amendments to his article, including the following: “Among the thirteen officer ranks of the command staff of the cruiser Zhemchug, there was no lieutenant Cherepkov, and he was killed There was only one officer in this battle, namely midshipman Sipailo, so the information I received from the caretaker of the Penang cemetery does not correspond to reality.” But in reality and on this score there are documents in the Russian State Administration of the Navy “Lieutenant” Alexey Cherepkov was a non-commissioned officer, senior miner of the cruiser “Orel”, who died on February 2, 1915 as a result of an accident during diving work on the “Pearl” and was buried nearby with the mass grave of his sailors.

As for the second surname Zpepuksh, among others placed on the slab, mentioned by the author of the essay and translated as Shenykin, then it or similar to it is not in the lists of the lower ranks of “Pearls” who died in battle and died from wounds, nor in lists of surviving wounded listed in a special order of the commander of the Siberian Flotilla for recording a combat wound. It can be assumed that this is a deceased sailor from the Orel, since, apart from this cruiser, there were no other warships of the Russian fleet in Penang.

How many Russian sailors were buried in Penang? E. Chekulaeva gives the figure 82, identifying the number of those buried with the number of deaths, which was incorrectly indicated. After all, even the quote she quotes from a local newspaper says: “...Many of the bodies that were in the water were so disfigured that they were buried at sea.” This message is complemented by the Cossacks: “In the end, about 80 people died, many drowned, being wounded, some sank along with the ship’s hull.” And even without that it is clear that it is impossible to bury everyone who died when the ship sank at sea. The Cossacks, who tidied up the Russian graves in 1938, reported that they learned from the old nun and the cemetery caretaker who were present at the burial that a total of 24 people were buried.

In the early 70s, with the consent of the Malaysian government, it was decided to restore the dilapidated monument. In 1972, the Chief of the General Staff of the Navy informed the Soviet ambassador in Malaysia that the monument was ready and would be delivered to Penang by a merchant fleet vessel. It was assumed that the restored monument would be opened in 1974 on the 60th anniversary of the death of the “Pearl” with the participation of a warship of the Pacific Fleet. However, the opening of the monument took place only on February 5, 1976 and without the participation of a warship, which the authorities did not give permission to enter Penang. It is interesting to note that the Chinese Xinhua agency expressed protest in connection with the installation of a monument to “sailors of the aggressive Navy of Tsarist Russia participants in the imperialist war.”

In October 1979, on the anniversary of the death of the Pearl, a wreath-laying ceremony took place in Penang, marked by a note in Pravda. And in May 1990, the large anti-submarine ship of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Tributs, came to Penang on an official visit, whose crew laid wreaths at the monument to the fallen Pacific sailors.

In conclusion, in addition to the above-mentioned names of the deceased midshipman Sipailo and the seven sailors who died from wounds, we present a list of the lower ranks of the crew of the cruiser “Pearl” who died in battle on October 15/28, 1914 (the list is stored in the Russian State Administration of the Navy.) These are the 80 names and surnames:

Averyanov Petr, Akimov Sergey, Alexandrov Alexander, Alekseev Nikolay, Babkin Ivan, Baev Nikolay, Baranov Fedor, Boyko Afanasy, Vavilov Egor, Vagin Georgy, Dedov Anisim, Demin Andrey, Zherebtsov Peter, Kalinin Stepan, Kirillov Daniil, Kiryanov Fedor, Kistenev Afanasy , Kovalchuk Moses, Kolesnikov Alexey, Kolesnikov Mikhail, Kolobov Trofim, Kolpashnikov Alexander, Korneev Philip, Kostyrev Yakov, Kosyrev-Kolesnikov Pavel, Kupriyanov Yakov, Kurbatov Pimen, Levashov-Lushkin Evdokim, Leus Gury, Lobanov Dmitry, Loginov Kuzma, Maltsev Yakov, Merkulov Fedor, Musyak Afanasy, Negodyaev Ilya, Nifontov Feoktist, Novikov Grigory, Ogaryshev Ivan, Panin Petr, Pekshev Sergey, Permykin Mikhail, Pichugin Vasily, Pozhitkov Alexey, Ponomarev Ignatiy, Popov Yakov, Prokhorov Alexander, Savin Vasily, Savinov Diomede, Sadov Ivan , Semkin Alexey, Serovikov Dmitry, Sigailo Artemy, Simagin Ivan, Sitkov Gerasim, Sudorgin Petr, Sukhikh Yakov, Sysoev Petr, Sychev Egor, Telegin Fedor, Tenikov Roman, Terentyev Arseny, Tintyakov Lavrentiy, Tomkovich Alexander, Tretyakov Ilya, Fedorov Andrian , Fedoseev Stepan, Fominykh Illarion, Frolkov Alexey, Khoroshkov Ivan, Khristoforov Zakhar, Khristoforov Stepan, Chadov Ivan, Chulanov Semyon, Shebalin Sergey, Shepelin Afanasy, Shishkin Dmitry, Shcheglov Andrey, Shmyg Vasily, Yakovlev Ivan, Yakushev Ignatius.

By publishing this mournful list, we hope that someone will discover the name of their ancestor.

From now on, one of the countless Russian graves scattered around the world has ceased to be nameless.

V. Lobytsyn, I. Stolyarov, I. Alabin | Photo by I. Zakharchenko

cruiser "Zhemchug" in Vladivostok, 1906

Armored cruiser of the second rank "Pearl"was built in St. Petersburg at the shipyards of the Nevsky Plant. Launched on August 14, 1903 and put into operation in September 1904. Tactical and technical parameters of the ship:

Displacement 3380 tons, main dimensions 111.2 - 12.8 m - 5.31 m. Draft 5.31 m. Reservation Armored deck - 30 mm Armored deck slopes - 50 mm Conning tower - 30 mm.

Power plant: 2 vertical triple expansion steam engines, 16 water tube boilers of the Yarrow system. Power 11,180 l. With. Propellers 2. Speed 24 knots (44.4 km/h). Cruising range 4500 nautical miles (at 10 knots). Crew: 11 officers, 333 sailors.

Weapons:

Artillery weapons: 8 × 120 mm/45, 6 × 47 mm/43, 2 × 37 mm/23, 1 × 64 mm (airborne), 4 7.62 mm machine guns.

Mine and torpedo armament: three 381-mm surface torpedo tubes (11 torpedoes).

On October 2, 1904, as part of a detachment of warships under the command of Rear Admiral Enquist, the “Pearl” left Libau and began its transition to the Far East, to Port Arthur.The lead cruiser in the detachment was the 2nd rank cruiser Almaz. “Pearl” took place third in the column, behind “Svetlana”... Ahead, across three oceans, lay the Tsushima Strait.

cruiser “Pearl on the Revel roadstead. 1904

...The auxiliary cruiser of the Japanese fleet "Shinano-Maru", which was in the patrol chain, discovered the Russian squadron at 4.00 in the morning on May 14, 1905 and immediately reported its coordinates by radio.

At about 6.00, the cruiser Izumi was spotted on the right heading. From that moment on, Japanese scouts continuously accompanied the Russians. After 9.00 the combat alarm was sounded, "Pearl" and "Emerald" moved forward and to the sides of the squadron. The morning was hazy and the end of the column was not visible, the wind was southwest 4 - 5, the cruisers were rocking. "Pearl" drove out of the way the junk heading towards Fr. Tsushima, they feared that such ships could drop floating mines in front of the squadron. An hour later, on the “Pearl” they noticed a steamer without a flag, which was moving from the west to cross the course of the squadron. The cruiser came at him at full speed and, firing a shot under the nose from a 47-mm gun, forced him to stop. A boat was lowered from the steamer, which was immediately smashed against the side by the waves. Approaching half a cable, we saw Japanese in national clothes on the deck, kneeling and begging for mercy. A sign ordered them to leave, which they did with great haste. “Pearl” returned to its place.

cruisers "Aurora", "Zhemchug" and "Oleg" (from left to right) on the roadstead of Manila, June-October 1905

At 12.00, already in the Tsushima Strait, the ships changed course to northeast 23°. Soon the first armored detachment left the general column to the right, while the “Pearl” was ordered to move abeam the “Eagle”, followed by the “Emerald” and four destroyers of the 1st mine detachment.

At 13.20, the main enemy forces appeared from the fog, marching in one wake column. When the Japanese battleships set a new course, the Russian squadron, which had not yet completed its formation into one column, opened fire. A few minutes later, the Japanese began to respond, concentrating fire on the flagship ships - "Prince Suvorov" and "Oslyab". The Zhemchug was on the right abeam of the latter, and all the flights were centered around it. When the Oslyabya, heeling to the left side and burying its nose, went out of order to the right of the squadron, the Pearl cut the line between the Eagle and the Sisoi the Great and headed towards the sinking battleship, firing at the end Japanese ships. At this time, a 152-mm shell hit the entrance hatch of the commander’s quarters in the stern and disabled the servant of the left 120-mm gun No. 8. Lieutenant Baron Wrangel was mortally wounded by the same shell; Midshipman Kiselev was also slightly wounded. To get out of the fire zone and return to the Eagle’s abeam, the Zhemchug commander decided to bypass Nebogatov’s detachment from the stern, however, realizing that this would take a lot of time, he cut through the formation between the coastal defense battleships and found himself among the transports.

cruiser "Pearl". 1905

"Izumrud" opened fire on Japanese ships in the gap between "Admiral Nakhimov" and "Oleg". Due to the confusion in the formation of transports, which darted from side to side, the Emerald often had to change course, stop the vehicles in order to avoid collisions with transports and destroyers, while excess steam was released into refrigerators that leaked.

"Pearl" at this time was approaching the lead battleships of the Russian column. "Prince Suvorov" turned to the left, its pipes and masts were already knocked down, and "Alexander III", which became the lead, turned to the right. Having noticed the destroyers near the Alexander III and believing that the admiral might be on them, the Pearl went towards them at full speed, preparing the whaleboat for launching. The destroyers, on one of which it was possible to see the flag officer of the squadron, did not linger and left. At this time, a Japanese armored detachment approached and opened fire on the Alexander III. When the distance to the enemy decreased to 25 kbt, the "Pearl" was given speed, and it left the fire zone, keeping behind the destroyers. At this time, the shell hit the middle pipe of the cruiser, the fragments scattered in different directions hit the right waist 120-mm gun No. 1, disabled its servants and ignited the cartridges in the fenders of the first shots that had not been fired earlier (in the Battle of Tsushima, similar cases happened on many ships). In addition, three cartridges located on the deck of the gun also ignited. At the same time, the cartridges burst, and unburned gunpowder was scattered throughout the ship. Midshipman Ratkov was shell-shocked by one of the cartridges. Fragments of the same shell, piercing the forward pipe, hit the bow bridge, where midshipman Tavastshern was killed and three lower ranks were wounded. At 16.10, in order not to interfere with the fire of its battleships, the “Pearl” joined the detachment of cruisers, entering the wake of the “Vladimir Monomakh”, and exchanged fire with the Japanese cruisers attacking the transports. At 17.25 the battle stopped. The battleships lined up in a column led by the Borodino; the Prince Suvorov and Oslyabi were missing. “Pearl” followed “Almaz” on the shell of “Oleg” at a distance of 5 kbt. It seemed that the battle was over and the road to Vladivostok was open...

But at 18.00 the battle resumed. The destroyer Buiny approached, holding a signal: “Admiral on the destroyer,” although no one knew which one. At the same time, they saw a signal on the mast of the Anadyr transport: “The Admiral transfers command to Admiral Nebogatov,” and on the “Nicholas I”: “Follow me.”

cruiser "Pearl after 1909"

Soon, a semaphore was sent from the Admiral Ushakov about the critical situation of the Alexander III, but the commander of the Emerald did not dare to approach him, since he was between the columns of battleships of both fighting sides. When "Alexander III" capsized, "Emerald" approached the place of his death, stopped the cars and began to prepare the rowing boat for launching, throwing off life preservers and bunks. The enemy armored cruisers appeared and opened fire on the stationary Emerald. When the distance decreased to 20 kbt, not wanting to tempt fate any longer, the Russian cruiser set sail. Soon he witnessed the death of the Borodin, which, after being hit by several large shells, went to the right and disappeared. "Nicholas I" bypassed "Eagle" and became the lead. At dusk the artillery duel stopped.

On the night from the fourteenth to the fifteenth of May something happened that was vaguely mentioned in Russia, but was never officially made public. Rear Admiral Enquist, despite the demands of the officers to break through to Vladivostok, decided to withdraw the cruisers “Zhemchug”, “Oleg” and “Aurora”, yes, the very symbol of the revolution, whose one-to-one scale model stands in eternal berth in St. – St. Petersburg, to the Philippines, to Manila and interning. Who knows, maybe it was then that it broke. Something that can never be restored and something that will become one of the reasons for the tragic death in nine years...

ships of Rear Admiral Enquist's detachment "Pearl", "Aurora" and "Oleg" on the roadstead of Manila, June-October 1905

And the Russian Fleet continued to fight and die... True, there was also a counter detachment - Admiral Nebogatova, who, between dishonor and death, chose the former, lowering the St. Andrew's Flags. There was the “Admiral Ushakov”, who fought alone against the entire Fleet of Admiral Togo, there was the “Rurik”, “Emerald” and many other, already forgotten ships and their crews. And the cruiser that left the battle is still ship No. 1... Such different destinies, different shores...

On August 23, 1905, the Portsmouth Peace Treaty between Russia and Japan was signed in the United States, and in anticipation of its ratification, the ships of the Russian detachment began preparations for returning to their homeland. "Pearl", as less damaged in the battle, was prepared for the ocean crossing by September 18, the rest - by October 5. On September 28, “Pearl” and “Aurora” went to sea to test the machines. And on the morning of October 9, 1905, Rear Admiral O.A. Enquist received official notification from the American commander Admiral Reiter that the detachment was free.

damage to the cruiser "Pearl" in the Battle of Tsushima

In January 1905, the cruiser's crew took an active part in the riots that took place in Vladivostok. After which, it was disbanded and partially tried by a military tribunal. Until 1907, the ship was listed in reserve, after which it was commissioned and enlisted in the Siberian Flotilla.

With the outbreak of the First World War, Russian cruisers were attached to the Allied fleet and came under the command of the English naval command. On August 21, 1914, “Pearl” received a personal task to inspect the sea area to the south of the island of Formosa.

Somewhere, far away in Europe, there was a bloody war, which throughout the world, except the USSR, would later be called the Great. A war that destroyed all old ideas and concepts and heralded the creation of a new world, a new civilization. And far, far away from the war, in the heavenly waters of the Indian Ocean, the cruiser of the Russian Empire's naval fleet "Pearl" did not even notice it.

"Pearl" as part of the Siberian flotilla

From the very beginning of the combat patrol, the ship’s commander, captain 2nd rank, Baron Cherkasov established a “resort” service mode for the team. When ships appeared on the horizon, the combat alarm was not sounded. There was no rest schedule for the crew; the servants were not at the guns at night. The mine devices were not loaded. When anchored in the port, the all-clear was played and the anchor lights were turned on, the signal watch did not intensify. Outsiders had the opportunity to visit the cruiser, and they went down to any premises. In September, the “Pearl” escorted Allied transports, while the ship’s commander took liberties when using radio communications: while off the Philippine Islands, he sent an unencrypted telegram to the “Askold” indicating his location. To be honest, reading something like this makes me dumbfounded. How so. How can this even happen, especially during the war, at a time when the German squadron of Admiral von Spee is crushing the British at Coronel, and shipping in the Indian Ocean is paralyzed by the Emden raider. What level of combat training did the crew have? When was the last time shooting practice took place? No matter how much I rummaged through materials on “Pearls,” I never found an answer. Truly, everyone chooses their own destiny...

Here is another episode, insignificant at first glance. In early October, “Pearl” was sent to the Nicobar and Andaman Islands for inspection. Having completed the mission, the Pearl stopped at the exposed port of Blair to load coal, with full lights on and no staff at the guns. Cherkasov himself, taking five officers with him, went ashore and stayed there all evening, although he was informed that the Emden appeared three times in the area of this port. The Emden simply did not find the Russian cruiser there. Otherwise, the tragedy would have happened much earlier...

On October 13 (26, new style), the Pearl returned to the port of Penang, on the island of the same name in the Strait of Malacca, from where at the end of September it set out on a voyage in search of the German cruiser Emden. The commander of the “Pearl,” Captain 2nd Rank Baron I.A. Cherkasov, received permission from the English Admiral Jeram, under whose command he was, for a seven-day visit to overhaul the mechanisms and clean the boilers. In connection with the actions of the Emden in this area, the commander of the Russian cruiser was advised to take all precautions while anchored in Penang Bay.

the mast of the "Pearl" at the site of its death

But Captain Cherkasov did not take the necessary measures, he did not do anything at all... On the evening of October 14, he himself went ashore to his wife, whom he had summoned to Penang from Vladivostok during the stay of the “Pearl”. And the Emden was already approaching the harbor...

The cruiser was sleeping peacefully. Even his watch, apparently, did not recognize the German raider in the Emden.

The dark silhouette of the Russian cruiser, illuminated by peacetime lights, was an ideal target for the Emden's torpedo tubes.

At 05:18 Captain 2nd Rank Müller ordered to open fire. Mine officer Lieutenant Vitgeft pulled the release lever of the torpedo tube. And then the guns of the German cruiser struck with a broadside salvo, and the German flag hoisted from the mast.

It took the torpedo 10 seconds to travel the distance to the sleepy Russian cruiser and hit it on the side behind the last pipe. A large column of water and fire rose above the “Pearl”, the stern of the Russian cruiser was thrown up, and then it quickly settled into the water almost to the stern flagpole. Meanwhile, shells from the Emden's five onboard guns tore apart the bow of the Zhemchug, where the Russian sailors' quarters were located.

mass grave on Penang island

The bow and stern parts of the Russian cruiser were engulfed in flames, the bow superstructure was destroyed, and the surviving sailors were rushing around the deck in panic.

Müller turned sharply to the left, approaching the merchant ships moored in another part of the harbor - mainly British and Japanese.

While the Emden was turning around, several shells whizzed past it. The surviving sailors of the "Pearl" reached the guns and opened fire on the "Emden". Their 120-mm shells, flying over the Emden, exploded among merchant ships, causing damage to them, playing into the hands of those same Germans...

Panic broke out on the Zhemchug, and part of the crew threw themselves overboard. The senior officer of the cruiser Kulibin and the artillery officer Rybaltovsky managed to restore relative order, but the people who stood at the guns did not find the shells - the supply elevators were not working. Moreover, the artillery cellars were closed and there were no keys. The locks had to be broken...

Rybaltovsky himself opened fire from the stern gun, firing several shots. Midshipman Sipailo opened fire from the bow gun and, according to the recollections of the crew members, with the first shot he scored a hit that caused a fire. The second shot of the Sipailo cannon coincided with a direct hit from a German shell, which destroyed the gun and all the people near it. Just ten minutes. Panic of the untrained crew. Lack of struggle for survivability, bordering on the crime of violating the rules for storing ammunition. Closed cellars, with unknown keys, uncharged torpedo tubes, no watch. Even if there had been no Emden, the crew would have had to be disbanded and the crew put on trial….

It was a hundred years ago...

« On the twenty-sixth of July two thousand and five, the Baltic Fleet patrol ship "Indomitable" completed the passage from Baltiysk to St. Petersburg to participate in the parade on the occasion of Navy Day and, in accordance with the disposition, took its place at the Lieutenant Schmidt Bridge, standing on two stationary barrels ….

DvOn July 19, I, as part of the commission of the headquarters of the Leningrad naval base, inspected the ship. It was very interesting, because nine years ago it was the “Indomitable” that fired two practical torpedoes at the “Chabanenko”, and I destroyed them. What I saw was not only disappointing, it left me in a state of stupor. By and large, he had to be urgently taken to Kronstadt, declared an organizational period and prepared for the return transition. The decomposition of the crew, primarily the officers, reached a critical state. The ammunition was stored with flagrant violations, and the fire safety systems were out of order. The personnel have not been trained. To send such a ship out to sea, especially to place it in the center of St. Petersburg, was a crime. This is exactly what I reported to the fleet headquarters commission. After my report, Deputy Chief of Staff Captain 1st Rank Yurchenko, it was I who was accused of all mortal sins, I am still surprised that the death of Pompeii was not also pinned on me. I was removed from the preparations for the festive events on the Neva. In short, it was decided that “The show will go on!”

patrol ship "Indomitable" in St. Petersburg

The show continued on the thirtieth of July, in the evening, on the eve of the holiday. During the next training session, the boat with the miners was prevented from approaching the dummy of a floating mine, in which a low-power demolition charge was used, by boats with spectators surrounding the ship, the wave from which the dummy was nailed to the side of the ship. There was an explosion and water began to flow into the ship. The untrained crew began the fight for survivability late; the bulkheads between the compartments were torn. The ship began to sink directly opposite the bulls of the Lieutenant Schmidt Bridge......

The patrol ship was saved by the emergency party of the small anti-submarine ship Zelenodolsk, which was standing nearby. Tugs from the Severnaya Verf shipyard dragged the ship to the plant and placed it in an emergency dock. Early in the morning of the thirty-first of July, Navy Day, I was already on board. The first thing that struck me was the deserted and extinct ship. The ship enters the emergency dock without unloading ammunition, and safety measures must be increased. Here everything was the other way around. Silence. The commanders of the mine-torpedo and missile-artillery combat units were not on board, their officers were lying dead drunk in their cabins, as were high-ranking officials of the fleet headquarters and the Leningrad naval base... At the Watch post I managed to find sailors patrolling the cellars, with whom I began my rounds. The cellars with jet depth charges were flooded, there was no lighting, the flashlight beam illuminated the heavy carcasses of the bombs, from which, according to the sailors' report, the fuses had not been removed. Not a single explosion and fire safety system worked; missiles were dozing peacefully in tightly sealed and unventilated containers... A ten-minute walk away was the Kirovsky Zavod metro station... Sunday morning was beginning. The sun rose over the former city of Lenin.....” (A. Sotnik “Mine lives in the water”).

This was nine years ago...

... Of the 335 crew members of the Pearl, one officer and 80 non-commissioned officers and sailors were killed, seven died from their wounds later, nine officers and 113 conductors and sailors were wounded.

A naval court held in August 1915 in Vladivostok found the commander, captain 2nd rank Ivan Cherkasov, and the senior officer, senior lieutenant Nikolai Kulibin, who replaced the commander who had moved ashore, guilty of the death of the cruiser and people. They were deprived of “ranks and orders and other insignia”, expelled from naval service and “after deprivation of the nobility and all special rights and benefits” they were sent to “correctional prison departments of the civil department”: Cherkasov - for 3.5 years, and Kulibin - for 1.5 years. By the Supreme Confirmation of the verdict of the Vladivostok Naval Court, both of them were demoted to sailors and sent to the front. Contrary to the assertion of the author of the essay “At Dawn, in Penang...”, the archives contain information - and quite complete information - about their further fate. Sailor 2nd article Baron Ivan Cherkasov fought on the Caucasus Front in the Urmia-Van Lake Flotilla, was awarded the soldier's Cross of St. George and in April 1917 was restored to the rank of captain 2nd rank. It is known that I.A. Cherkasov died in France in March 1942 and was buried in the Sainte-Gensvieve-des-Bois cemetery near Paris. Sailor Nikolai Kulibin fought on the Western Front in a naval brigade, received two Crosses of St. George and was restored to rank in September 1916. Soon he was promoted to captain 2nd rank. He died in hospital in August 1918 from a wound received back in the February days of 1917, when he commanded the destroyer Movable.

Note. List of lower ranks of the crew of the cruiser "Pearl" who died in battle on October 15/28, 1914 (the list is stored in the Russian State Administration of the Navy.)

Averyanov Petr, Akimov Sergey, Alexandrov Alexander, Alekseev Nikolay, Babkin Ivan, Baev Nikolay, Baranov Fedor, Boyko Afanasy, Vavilov Egor, Vagin Georgy, Dedov Anisim, Demin Andrey, Zherebtsov Peter, Kalinin Stepan, Kirillov Daniil, Kiryanov Fedor, Kistenev Afanasy , Kovalchuk Moses, Kolesnikov Alexey, Kolesnikov Mikhail, Kolobov Trofim, Kolpashnikov Alexander, Korneev Philip, Kostyrev Yakov, Kosyrev-Kolesnikov Pavel, Kupriyanov Yakov, Kurbatov Pimen, Levashov-Lushkin Evdokim, Leus Gury, Lobanov Dmitry, Loginov Kuzma, Maltsev Yakov, Merkulov Fedor, Musyak Afanasy, Negodyaev Ilya, Nifontov Feoktist, Novikov Grigory, Ogaryshev Ivan, Panin Petr, Pekshev Sergey, Permykin Mikhail, Pichugin Vasily, Pozhitkov Alexey, Ponomarev Ignatiy, Popov Yakov, Prokhorov Alexander, Savin Vasily, Savinov Diomede, Sadov Ivan , Semkin Alexey, Serovikov Dmitry, Sigailo Artemy, Simagin Ivan, Sitkov Gerasim, Sudorgin Petr, Sukhikh Yakov, Sysoev Petr, Sychev Egor, Telegin Fedor, Tenikov Roman, Terentyev Arseny, Tintyakov Lavrentiy, Tomkovich Alexander, Tretyakov Ilya, Fedorov Andrian , Fedoseev Stepan, Fominykh Illarion, Frolkov Alexey, Khoroshkov Ivan, Khristoforov Zakhar, Khristoforov Stepan, Chadov Ivan, Chulanov Semyon, Shebalin Sergey, Shepelin Afanasy, Shishkin Dmitry, Shcheglov Andrey, Shmyg Vasily, Yakovlev Ivan, Yakushev Ignatius.

Who knows, maybe someone will find their ancestors among these names?

10 minutes containing the glory of the dead and the dishonor of the living. Everlasting memory…

Material from Wikipedia - the free encyclopedia

| "Pearl" | |

|---|---|

| Service: | Russia, Russia |

| Vessel class and type | Cruiser 2nd rank |

| Home port | Saint Petersburg Vladivostok |

| Organization | Baltic Fleet Second Pacific Squadron Siberian military flotilla |

| Manufacturer | Nevsky Plant |

| Launched | August 14, 1903 |

| Commissioned | September 1904 |

| Removed from the fleet | 1914 |

| Status | On October 15, 1914, she was sunk by the cruiser Emden in Penang. |

| Main characteristics | |

| Displacement | 3380 tons |

| Length | 111.2 m |

| Width | 12.8 m |

| Draft | 5.31 m |

| Booking | Armor deck- 30 mm Armor deck slopes- 50 mm Conning tower- 30 mm |

| Engines | 2 vertical triple expansion steam engines, 16 Jarrow water tube boilers |

| Power | 11,180 l. With. (8.22 MW) |

| Mover | 2 screws |

| Travel speed | 24 knots (44.4 km/h) |

| Cruising range | 4500 nautical miles (at 10 knots) |

| Crew | 11 officers, 333 sailors |

| Armament | |

| Artillery | 8 × 120 mm/45, 6 × 47 mm/43, 2 × 37 mm/23, 1 × 64 mm (airborne), 4 7.62 mm machine guns |

| Mine and torpedo weapons | 3×1-381 mm surface torpedo tubes (11 torpedoes) |

Construction and testing

By the end of the day, “Pearl” finally joined the detachment of cruisers of Rear Admiral O. A. Enquist, taking a place on the left beam of the “Aurora”. At night the detachment tried to change course, but invariably ran into Japanese destroyers. Captain 2nd Rank Levitsky tried to find out the intentions of the flagship, but received only an order to follow the detachment to Manila for repairs. On May 21, the Russian cruisers dropped anchor in Manila, and on May 25, by order from St. Petersburg, they were interned until the end of hostilities.

After peace was concluded with Japan, the Zhemchug began preparing for the transition to Russia. According to the highest approved distribution of interned ships, he was to move to Vladivostok and become part of the Siberian Flotilla. On October 14 at 12.20 "Pearl" left Manila and headed to its destination.

As part of the Siberian flotilla

During the uprising in Vladivostok on January 10, 1906, the cruiser's crew joined the rebel garrison and took part in street battles. After the unrest was quelled, the cruiser's crew was disarmed and written off to shore, with 402 sailors being put on trial.

During the uprising in Vladivostok on January 10, 1906, the cruiser's crew joined the rebel garrison and took part in street battles. After the unrest was quelled, the cruiser's crew was disarmed and written off to shore, with 402 sailors being put on trial.

Despite the poor technical condition, the cruiser annually sailed through the bays of Primorye and, alternating with the gunboat Manchzhur, carried out station duty in Shanghai. In addition, the cruiser made short trips to Chinese, Korean and Japanese ports and was used as a target for training submariners. In 1910, Zhemchug was put in for major repairs.

The repaired cruiser spent the 1911 campaign on practical voyages as the flagship ship of the flotilla commander. In May, the Minister of War inspected Peter the Great Bay from aboard the Zhemchug. In 1912, the ship was placed in the armed reserve. The commander of the cruiser was the hero of the Russian-Japanese War, Captain 2nd Rank Ivanov 13th. The following year, the cruiser performed stationary duties in Shanghai and Hankou. He met 1914 there, guarding Russian citizens and reporting on the situation in China, where the revolution took place. In mid-May, “Pearl” returned to Vladivostok, and a month later the commander was once again changed, who became captain 2nd rank Baron I. A. Cherkasov.

Cruiser in the First World War

Protection of Entente maritime communications

In the 1990s, the “Pearl” was partially raised and dismantled by English specialists.

Memory of the cruiser

The first monument to the cruiser Zhemchug was erected in 1915 by sailors of the auxiliary cruiser Orel. In February 1938, Cossack emigrants who found themselves on tour in Penang put the grave in order, straightened the cross and installed a memorial plaque with nine names, which they managed to find out from the cemetery archives). In February 1976, a new monument appeared on the grave in the form of a stone cube with the inscription “To the Russian sailors of the cruiser “Zhemchug” - a grateful homeland,” created on the initiative of the USSR. In the 1990s, a plate with the names of the cruiser officers was added.

The first monument to the cruiser Zhemchug was erected in 1915 by sailors of the auxiliary cruiser Orel. In February 1938, Cossack emigrants who found themselves on tour in Penang put the grave in order, straightened the cross and installed a memorial plaque with nine names, which they managed to find out from the cemetery archives). In February 1976, a new monument appeared on the grave in the form of a stone cube with the inscription “To the Russian sailors of the cruiser “Zhemchug” - a grateful homeland,” created on the initiative of the USSR. In the 1990s, a plate with the names of the cruiser officers was added.

Write a review on the article "Pearl (armored cruiser)"

Notes

Literature

- V. V. Khromov. Cruisers of the “Pearl” type / A. S. Raguzin. - M.: Modeler-designer, 2005. - 32 p. - (Marine collection No. 1 (70) / 2005). - 4000 copies.

- Cruisers "Pearl" and "Izumrud"; Alliluev, A. A.; Bogdanov, M. A. - Publishing house: St. Petersburg: LeKo, 2004; ISBN 5-902236-17-7

- Corbett J. Operations of the English fleet in the First World War. - Mn.: Harvest LLC, 2003. - 480 p. (Military History Library). ISBN 985-13-1058-1

- Krinitsky N. N. Auxiliary cruiser of the Siberian flotilla “Orel” (Russian) // Russia and the Asia-Pacific region. - 2005 - No. 4. .

- Taras A. Ships of the Russian Imperial Navy 1892-1917. - Harvest, 2000. - ISBN 9854338886.

- About monuments to sailors from the Russian cruiser “Pearl” on the islands of Penang and Jerejak (Malaysia) (Russian) // Embassy of the Russian Federation in Malaysia. - 2006.

- Russian cruisers protecting the ocean communications of the Entente A. V. Nevsky (Journal Gangut No. 34) based on materials from the Russian State Academy of Military Fleet

Links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Excerpt characterizing Zhemchug (armored cruiser)

“One was hit,” answered the officer on duty, “and the other, I can’t understand; I myself was there all the time and gave orders and just drove away... It was hot, really,” he added modestly.Someone said that Captain Tushin was standing here near the village, and that they had already sent for him.

“Yes, there you were,” said Prince Bagration, turning to Prince Andrei.

“Well, we didn’t move in together for a bit,” said the officer on duty, smiling pleasantly at Bolkonsky.

“I did not have the pleasure of seeing you,” said Prince Andrei coldly and abruptly.

Everyone was silent. Tushin appeared on the threshold, timidly making his way from behind the generals. Walking around the generals in a cramped hut, embarrassed, as always, at the sight of his superiors, Tushin did not notice the flagpole and stumbled over it. Several voices laughed.

– How was the weapon abandoned? – Bagration asked, frowning not so much at the captain as at those laughing, among whom Zherkov’s voice was heard loudest.

Tushin now only, at the sight of the formidable authorities, imagined in all horror his guilt and shame in the fact that he, having remained alive, had lost two guns. He was so excited that until that moment he did not have time to think about it. The officers' laughter confused him even more. He stood in front of Bagration with a trembling lower jaw and barely said:

– I don’t know... Your Excellency... there were no people, Your Excellency.

– You could have taken it from cover!

Tushin did not say that there was no cover, although this was the absolute truth. He was afraid to let down another boss and silently, with fixed eyes, looked straight into Bagration’s face, like a confused student looks into the eyes of an examiner.

The silence was quite long. Prince Bagration, apparently not wanting to be strict, had nothing to say; the rest did not dare to intervene in the conversation. Prince Andrey looked at Tushin from under his brows, and his fingers moved nervously.

“Your Excellency,” Prince Andrei interrupted the silence with his sharp voice, “you deigned to send me to Captain Tushin’s battery.” I was there and found two thirds of the men and horses killed, two guns mangled, and no cover.

Prince Bagration and Tushin now looked equally stubbornly at Bolkonsky, who was speaking restrainedly and excitedly.

“And if, Your Excellency, allow me to express my opinion,” he continued, “then we owe the success of the day most of all to the action of this battery and the heroic fortitude of Captain Tushin and his company,” said Prince Andrei and, without waiting for an answer, he immediately stood up and walked away from the table.

Prince Bagration looked at Tushin and, apparently not wanting to show distrust of Bolkonsky’s harsh judgment and, at the same time, feeling unable to fully believe him, bowed his head and told Tushin that he could go. Prince Andrei followed him out.

“Thank you, I helped you out, my dear,” Tushin told him.

Prince Andrei looked at Tushin and, without saying anything, walked away from him. Prince Andrei was sad and hard. It was all so strange, so unlike what he had hoped for.

"Who are they? Why are they? What do they need? And when will all this end? thought Rostov, looking at the changing shadows in front of him. The pain in my arm became more and more excruciating. Sleep was falling irresistibly, red circles were jumping in my eyes, and the impression of these voices and these faces and the feeling of loneliness merged with a feeling of pain. It was they, these soldiers, wounded and unwounded, - it was they who pressed, and weighed down, and turned out the veins, and burned the meat in his broken arm and shoulder. To get rid of them, he closed his eyes.

He forgot himself for one minute, but in this short period of oblivion he saw countless objects in his dreams: he saw his mother and her big white hand, he saw Sonya’s thin shoulders, Natasha’s eyes and laughter, and Denisov with his voice and mustache, and Telyanin , and his whole story with Telyanin and Bogdanich. This whole story was one and the same thing: this soldier with a sharp voice, and this whole story and this soldier so painfully, relentlessly held, pressed and all pulled his hand in one direction. He tried to move away from them, but they did not let go of his shoulder, not even a hair, not even for a second. It wouldn’t hurt, it would be healthy if they didn’t pull on it; but it was impossible to get rid of them.

He opened his eyes and looked up. The black canopy of night hung an arshin above the light of the coals. In this light, particles of falling snow flew. Tushin did not return, the doctor did not come. He was alone, only some soldier was now sitting naked on the other side of the fire and warming his thin yellow body.

“Nobody needs me! - thought Rostov. - There is no one to help or feel sorry for. And I was once at home, strong, cheerful, loved.” “He sighed and involuntarily groaned with a sigh.

- Oh, what hurts? - asked the soldier, shaking his shirt over the fire, and, without waiting for an answer, he grunted and added: - You never know how many people have been spoiled in a day - passion!

Rostov did not listen to the soldier. He looked at the snowflakes fluttering over the fire and remembered the Russian winter with a warm, bright house, a fluffy fur coat, fast sleighs, a healthy body and with all the love and care of his family. “And why did I come here!” he thought.

The next day, the French did not resume the attack, and the rest of Bagration’s detachment joined Kutuzov’s army.

Prince Vasily did not think about his plans. He even less thought of doing evil to people in order to gain benefit. He was only a secular man who had succeeded in the world and made a habit out of this success. He constantly, depending on the circumstances, depending on his rapprochement with people, drew up various plans and considerations, of which he himself was not well aware, but which constituted the entire interest of his life. Not one or two such plans and considerations were in his mind, but dozens, of which some were just beginning to appear to him, others were achieved, and others were destroyed. He did not say to himself, for example: “This man is now in power, I must gain his trust and friendship and through him arrange for the issuance of a one-time allowance,” or he did not say to himself: “Pierre is rich, I must lure him to marry his daughter and borrow the 40 thousand I need”; but a man in strength met him, and at that very moment instinct told him that this man could be useful, and Prince Vasily became close to him and at the first opportunity, without preparation, by instinct, flattered, became familiar, talked about what what was needed.

Pierre was under his arm in Moscow, and Prince Vasily arranged for him to be appointed a chamber cadet, which was then equivalent to the rank of state councilor, and insisted that the young man go with him to St. Petersburg and stay in his house. As if absent-mindedly and at the same time with an undoubted confidence that this should be so, Prince Vasily did everything that was necessary in order to marry Pierre to his daughter. If Prince Vasily had thought about his plans ahead, he could not have had such naturalness in his manners and such simplicity and familiarity in his relations with all the people placed above and below himself. Something constantly attracted him to people stronger or richer than himself, and he was gifted with the rare art of catching exactly the moment when it was necessary and possible to take advantage of people.

Pierre, having unexpectedly become a rich man and Count Bezukhy, after recent loneliness and carelessness, felt so surrounded and busy that he could only be left alone with himself in bed. He had to sign papers, deal with government offices, the meaning of which he had no clear idea of, ask the chief manager about something, go to an estate near Moscow and receive many people who previously did not want to know about his existence, but now would offended and upset if he didn’t want to see them. All these various persons - businessmen, relatives, acquaintances - were all equally well disposed towards the young heir; all of them, obviously and undoubtedly, were convinced of the high merits of Pierre. He constantly heard the words: “With your extraordinary kindness,” or “with your wonderful heart,” or “you yourself are so pure, Count...” or “if only he were as smart as you,” etc., so he He sincerely began to believe in his extraordinary kindness and his extraordinary mind, especially since it always seemed to him, deep down in his soul, that he was really very kind and very smart. Even people who had previously been angry and obviously hostile became tender and loving towards him. Such an angry eldest of the princesses, with a long waist, with hair smoothed like a doll’s, came to Pierre’s room after the funeral. Lowering her eyes and constantly flushing, she told him that she was very sorry for the misunderstandings that had happened between them and that now she felt she had no right to ask for anything, except permission, after the blow that had befallen her, to stay for a few weeks in the house that she loved so much and where made so many sacrifices. She couldn't help but cry at these words. Touched that this statue-like princess could change so much, Pierre took her hand and asked for an apology, without knowing why. From that day on, the princess began to knit a striped scarf for Pierre and completely changed towards him.

– Do it for her, mon cher; “All the same, she suffered a lot from the dead man,” Prince Vasily told him, letting him sign some kind of paper in favor of the princess.

Prince Vasily decided that this bone, a bill of 30 thousand, had to be thrown to the poor princess so that it would not occur to her to talk about Prince Vasily’s participation in the mosaic portfolio business. Pierre signed the bill, and from then on the princess became even kinder. The younger sisters also became affectionate towards him, especially the youngest, pretty, with a mole, often embarrassed Pierre with her smiles and embarrassment at the sight of him.

It seemed so natural to Pierre that everyone loved him, it would seem so unnatural if someone did not love him, that he could not help but believe in the sincerity of the people around him. Moreover, he did not have time to ask himself about the sincerity or insincerity of these people. He constantly had no time, he constantly felt in a state of meek and cheerful intoxication. He felt like the center of some important general movement; felt that something was constantly expected of him; that if he didn’t do this, he would upset many and deprive them of what they expected, but if he did this and that, everything would be fine - and he did what was required of him, but something good remained ahead.

More than anyone else at this first time, Prince Vasily took possession of both Pierre’s affairs and himself. Since the death of Count Bezukhy, he has not let Pierre out of his hands. Prince Vasily had the appearance of a man weighed down by affairs, tired, exhausted, but out of compassion, unable to finally abandon this helpless young man, the son of his friend, to the mercy of fate and the swindlers, apres tout, [in the end,] and with such a huge fortune. In those few days that he stayed in Moscow after the death of Count Bezukhy, he called Pierre to himself or came to him himself and prescribed to him what needed to be done, in such a tone of fatigue and confidence, as if he was saying every time:

“Vous savez, que je suis accable d"affaires et que ce n"est que par pure charite, que je m"occupe de vous, et puis vous savez bien, que ce que je vous propose est la seule chose faisable." [ You know, I am swamped with business; but it would be merciless to leave you like this; of course, what I am telling you is the only possible one.]

“Well, my friend, tomorrow we’re going, finally,” he told him one day, closing his eyes, moving his fingers on his elbow and in such a tone, as if what he was saying had been decided a long time ago between them and could not be decided otherwise.

“We’re going tomorrow, I’ll give you a place in my stroller.” I am very happy. Everything important is over here. I should have needed it a long time ago. This is what I received from the chancellor. I asked him about you, and you were enlisted in the diplomatic corps and made a chamber cadet. Now the diplomatic path is open to you.

Despite the strength of the tone of fatigue and the confidence with which these words were spoken, Pierre, who had been thinking about his career for so long, wanted to object. But Prince Vasily interrupted him in that cooing, bassy tone that excluded the possibility of interrupting his speech and which he used when extreme persuasion was necessary.

- Mais, mon cher, [But, my dear,] I did it for myself, for my conscience, and there is nothing to thank me for. No one ever complained that he was too loved; and then, you are free, even if you quit tomorrow. You will see everything for yourself in St. Petersburg. And it’s high time for you to move away from these terrible memories. – Prince Vasily sighed. - Yes, yes, my soul. And let my valet ride in your carriage. Oh yes, I forgot,” Prince Vasily added, “you know, mon cher, that we had scores with the deceased, so I received it from Ryazan and will leave it: you don’t need it.” We will settle with you.

What Prince Vasily called from “Ryazan” were several thousand quitrents, which Prince Vasily kept for himself.

In St. Petersburg, as in Moscow, an atmosphere of gentle, loving people surrounded Pierre. He could not refuse the place or, rather, the title (because he did nothing) that Prince Vasily brought him, and there were so many acquaintances, calls and social activities that Pierre, even more than in Moscow, experienced a feeling of fog and haste and everything that is coming, but some good is not happening.

Many of his former bachelor society were not in St. Petersburg. The guard went on a campaign. Dolokhov was demoted, Anatole was in the army, in the provinces, Prince Andrei was abroad, and therefore Pierre was not able to spend his nights as he had previously liked to spend them, or to occasionally unwind in a friendly conversation with an older, respected friend. All his time was spent at dinners, balls and mainly with Prince Vasily - in the company of the fat princess, his wife, and the beautiful Helen.

Anna Pavlovna Scherer, like others, showed Pierre the change that had occurred in the public view of him.

Previously, Pierre, in the presence of Anna Pavlovna, constantly felt that what he was saying was indecent, tactless, and not what was needed; that his speeches, which seem smart to him while he prepares them in his imagination, become stupid as soon as he speaks loudly, and that, on the contrary, the stupidest speeches of Hippolytus come out smart and sweet. Now everything he said came out charmant. If even Anna Pavlovna did not say this, then he saw that she wanted to say it, and she only, in respect of his modesty, refrained from doing so.

At the beginning of the winter from 1805 to 1806, Pierre received from Anna Pavlovna the usual pink note with an invitation, which added: “Vous trouverez chez moi la belle Helene, qu"on ne se lasse jamais de voir.” [I will have a beautiful Helene , which you will never get tired of admiring.]

Reading this passage, Pierre felt for the first time that some kind of connection had formed between him and Helene, recognized by other people, and this thought at the same time frightened him, as if an obligation was being imposed on him that he could not keep. and together he liked it as a funny guess.

Anna Pavlovna's evening was the same as the first, only the novelty that Anna Pavlovna treated her guests to was now not Mortemart, but a diplomat who had arrived from Berlin and brought the latest details about the stay of Emperor Alexander in Potsdam and how the two highest each other swore there in an indissoluble alliance to defend the just cause against the enemy of the human race. Pierre was received by Anna Pavlovna with a tinge of sadness, which obviously related to the fresh loss that befell the young man, to the death of Count Bezukhy (everyone constantly considered it their duty to assure Pierre that he was very upset by the death of his father, whom he hardly knew) - and sadness exactly the same as the highest sadness that was expressed at the mention of the august Empress Maria Feodorovna. Pierre felt flattered by this. Anna Pavlovna, with her usual skill, arranged circles in her living room. The large circle, where Prince Vasily and the generals were, used a diplomat. Another mug was at the tea table. Pierre wanted to join the first, but Anna Pavlovna, who was in the irritated state of a commander on the battlefield, when thousands of new brilliant thoughts come that you barely have time to put into execution, Anna Pavlovna, seeing Pierre, touched his sleeve with her finger.

- Attendez, j "ai des vues sur vous pour ce soir. [I have plans for you this evening.] She looked at Helene and smiled at her. - Ma bonne Helene, il faut, que vous soyez charitable pour ma pauvre tante , qui a une adoration pour vous. Allez lui tenir compagnie pour 10 minutes. [My dear Helen, I need you to be compassionate towards my poor aunt, who has adoration for you. Stay with her for 10 minutes.] And so that you are not very it was boring, here’s a dear count who won’t refuse to follow you.

The beauty went to her aunt, but Anna Pavlovna still kept Pierre close to her, appearing as if she had one last necessary order to make.

– Isn’t she amazing? - she said to Pierre, pointing to the majestic beauty sailing away. - Et quelle tenue! [And how she holds herself!] For such a young girl and such tact, such a masterful ability to hold herself! It comes from the heart! Happy will be the one whose it will be! With her, the most unsecular husband will involuntarily occupy the most brilliant place in the world. Is not it? I just wanted to know your opinion,” and Anna Pavlovna released Pierre.

Pierre sincerely answered Anna Pavlovna in the affirmative to her question about Helen’s art of holding herself. If he ever thought about Helen, he thought specifically about her beauty and about her unusual calm ability to be silently worthy in the world.

Auntie accepted two young people into her corner, but it seemed that she wanted to hide her adoration for Helen and wanted to more express her fear of Anna Pavlovna. She looked at her niece, as if asking what she should do with these people. Moving away from them, Anna Pavlovna again touched Pierre’s sleeve with her finger and said:

- J"espere, que vous ne direz plus qu"on s"ennuie chez moi, [I hope you won’t say another time that I’m bored] - and looked at Helen.

Helen smiled with an expression that said that she did not admit the possibility that anyone could see her and not be admired. Auntie cleared her throat, swallowed her drool and said in French that she was very glad to see Helen; then she turned to Pierre with the same greeting and with the same mien. In the middle of a boring and stumbling conversation, Helen looked back at Pierre and smiled at him with that clear, beautiful smile with which she smiled at everyone. Pierre was so used to this smile, it expressed so little for him that he did not pay any attention to it. Auntie was talking at this time about the collection of snuff boxes that Pierre’s late father, Count Bezukhy, had, and showed her snuff box. Princess Helen asked to see the portrait of her aunt's husband, which was made on this snuff box.

“This was probably done by Vines,” said Pierre, naming the famous miniaturist, bending over to the table to pick up a snuffbox, and listening to the conversation at another table.

He stood up, wanting to go around, but the aunt handed the snuff box right across Helen, behind her. Helen leaned forward to make room and looked back, smiling. She was, as always at evenings, in a dress that was very open in front and back, according to the fashion of that time. Her bust, which always seemed marble to Pierre, was at such a close distance from his eyes that with his myopic eyes he involuntarily discerned the living beauty of her shoulders and neck, and so close to his lips that he had to bend down a little to touch her. He heard the warmth of her body, the smell of perfume and the creak of her corset as she moved. He did not see her marble beauty, which was one with her dress, he saw and felt all the charm of her body, which was covered only by clothes. And, once he saw this, he could not see otherwise, just as we cannot return to a deception once explained.

“So you haven’t noticed how beautiful I am until now? – Helen seemed to say. “Have you noticed that I’m a woman?” Yes, I am a woman who can belong to anyone and you too,” said her look. And at that very moment Pierre felt that Helen not only could, but had to be his wife, that it could not be otherwise.

He knew it at that moment as surely as he would have known it standing under the aisle with her. As it will be? and when? he did not know; he didn’t even know whether it would be good (he even felt that it was not good for some reason), but he knew that it would be.

Pierre lowered his eyes, raised them again and again wanted to see her as such a distant, alien beauty as he had seen her every day before; but he could no longer do this. He could not, just as a person who had previously looked in the fog at a blade of weeds and saw a tree in it, cannot, after seeing the blade of grass, again see a tree in it. She was terribly close to him. She already had power over him. And between him and her there were no longer any barriers, except for the barriers of his own will.

Two days ago, October 15/28, it was 100 years since the tragic death of the Russian cruiser Zhemchug, which was taken by surprise by the enemy. This event, soon described on the pages of all major newspapers, caused a noticeable response in society: grief over the loss of the cruiser and the death of part of its crew was mixed with indignation at the treachery of the “German” and the negligence of the captain of the “Pearl”, Baron I.A. Cherkasov.

The armored cruiser Zhemchug, in the presence of Emperor Nicholas II, was launched from the shipyards of the Nevsky Plant in August 1903, and a year later became part of the Second Pacific Squadron. Soon this warship had the opportunity to take part in the Russo-Japanese War. During the tragic Battle of Tsushima for the Russian fleet, the “Pearl” received 17 hits, but managed to escape from the enemy to Manila. Subsequently, the cruiser served as part of the Siberian flotilla, sailed through the bays of Primorye, and was the flagship of the flotilla commander.

In 1914, when the war with Germany broke out, the Pearl, together with the cruiser Askold, by decision of the Emperor, was attached to the Allied fleet, coming under the command of the English Vice Admiral Jeram, who sent Russian warships to Hong Kong. Having united with the English squadron, the Russian cruisers took on board British liaison officers and split up near the Philippines. The Pearl was responsible for escorting English and French transports transporting troops and cargo. At the end of September, the “Pearl” ended up off the Malaysian island of Penang (Prince of Wales Island), a small English port located near Singapore, where, at the insistence of its commander, Captain 2nd Rank Baron I.A. Cherkasov, it was undergoing repairs due to bad technical condition of the boiler installation.

“The situation was semi-peaceful,” Later, Lieutenant Yu.Yu. Rybaltovsky, who served on the “Pearl,” said. - The enemy Austro-German fleet was hiding far in Europe in its bases. The Pacific German squadron made its way to its homeland and was located somewhere off the coast of South America. The only threat was the cruiser Emden, wandering somewhere in the waters of the Indian Ocean, but according to British counterintelligence information, it was, in any case, no closer than a thousand miles from Penang.”

However, this parking lot turned out to be fatal for the “Pearl”. The information about the German cruiser was incorrect, and in the early morning of October 15/28, the Emden, having extinguished the lights and installed a false additional (fourth) pipe made of tarpaulin, which made its silhouette very similar to the British cruiser Yarmouth, deceived the French patrol and entered unhindered Penang harbor. The German sailors hoped to catch the French armored cruisers Montcalm and Duplex here and attack them while anchored. But instead of them, the Germans stumbled upon the practically defenseless Russian “Pearl”.

What happened next is described in the memoirs of the senior officer of the cruiser Emden, Helmut von Mücke: “Everyone had already decided that the expedition had failed, when suddenly among these “merchants” standing with anchor lights and with portholes illuminated from inside, some dark silhouette appeared without a single light. This is, of course, a warship. A few minutes later we were close enough to be convinced that this was indeed the case. (...) Finally, when the Emden passed at a distance of about 1 cable under the stern of the mysterious ship and came abeam of it, we finally established that it was the cruiser Zhemchug. Peace and silence reigned there. We were so close to him that in the weak light of the dawning day everything that was happening on the Russian cruiser was clearly visible. But neither the watch commander, nor the watchmen, nor the signalmen were visible. From a distance of about 1 cable. we fired our first mine from the right side apparatus and at the same moment opened fire with the whole side on the bow of the Pearl, where most of the crew was sleeping in their bunks. Our mine exploded in the stern of the cruiser. It was as if he was completely shaken by this explosion. The stern was thrown out of the water, and then it began to slowly sink. Only after this did the Russians discover signs of life... Meanwhile, our artillery maintained furious fire on the Zhemchug... The bow of the cruiser was riddled with bullets in a few minutes. The flames engulfed the entire forecastle. The opposite shore was visible through the holes in the side.”

Out of surprise, panic began on the “Pearl”; crew members began to throw themselves overboard. The officers quickly managed to restore order, but they were unable to resist the Emden - during repairs, all the boilers on the Russian cruiser were disabled, except for one, which could not provide a full power supply and operation of the shell elevators. As a result, when they stood up to the guns, the sailors discovered that most of them had no shells, since the supply elevators were not functioning. Senior artillery officer Yu.Yu. Rybaltovsky personally opened fire from the poop gun, achieving two hits on the German ship. The watch chief, midshipman A.K. Sipailo, managed to fire only one shot from the tank gun, but was immediately killed.

“Finally, on the Zhemchug they gathered their strength and opened fire on us,” recalled von Mücke. - The guns on it were larger than ours, and Russian shells could cause us great harm. Therefore, the commander decided to fire a second mine. "Emden", passing by "Pearl", turned around and headed towards it again. The second mine was fired from a distance of about two cables. A few seconds later, a terrible explosion was heard under the front bridge of the Russian cruiser.

A giant column of gray smoke, steam and water spray rose to a height of about 150 m. Parts of the ship's hull were torn off by the explosion and flew through the air. It was clear that the cruiser had broken in half. The bow part has separated. Then the entire ship was covered in smoke, and when it cleared, the cruiser was no longer visible, only fragments of its mast were sticking out of the water. People swarmed among the wreckage on the water.But Emden had no time for them". Switching to the French destroyer Musquet, which tried to detain the Emdem, the German cruiser sent it to the bottom, and then melted away in the early morning darkness...

“Pearl” completely went under water in a few seconds. “The first rays of the rising sun illuminated the already calm roadstead, on the surface of which people and Malay boats were swarming. It was local residents who saved wounded and drowning Russian sailors.”, - said a witness to the tragedy. The crew of the Russian cruiser lost a midshipman and 87 lower ranks; 9 officers and 113 sailors were injured of varying degrees of severity.

But this was the last success for Emdem. Having sent 22 steamers to the bottom in addition to two warships, already on October 27/November 9, 1914, the German ship was overtaken by the Australian cruiser Sydney and sunk during the battle. “Everyone probably remembers, or rather has not yet forgotten, how at the very beginning of the Great War, the German cruiser Emden caused terror in the waters of the Indian and partly the Pacific oceans,” wrote in 1938 the magazine of Russian military emigration "Chasovoy". - Cut off from its bases, deprived of any support, completely alone in distant enemy waters, the Emden was doomed to destruction. He knew this well and was ready to die, but before the moment when this death was about to occur, he decided to inflict the greatest harm on the enemy and, so to speak, sell his life dearly. Dozens of merchant ships and military transports of the allied fleet were sunk by it, but Emden’s biggest undertaking was the destruction of the Russian cruiser Zhemchug in the roadstead of the Penang port.”. The surviving part of the crew of the German cruiser was later personally received by Kaiser Wilhelm, who, in commemoration of his services, awarded Captain Karl von Müller the highest military honor of Prussia, the Order Pour le Mérite (Blauer Max), and all other sailors and their descendants the right to add the word "Emden" to their last names.