Student revolution in France 1968. The last uprising of intellectuals

This May, radical leftists around the world celebrated the 35th anniversary of the French Revolution, better known as Red May. Hundreds of thousands of students and workers, determined to overthrow capitalism, flooded the streets of French cities in those memorable May days, built barricades, fought with the police, and went on strikes. Despite the fact that Red May of 1968 was defeated, this historical event is a cult event for rebels all over the world, a celebration of rebellion against the bestial orders of capitalism and the ways of life of the old, thoroughly rotten patriarchal world. Let us learn for ourselves the lessons of this historical event, for the experience of Red May will be useful to us in FUTURE REVOLUTIONS OF THE XXI CENTURY!

GROWTH AT ANY COST

The post-war decades in France leading up to the 1968 revolution were marked by stable economic growth and, as a result, low unemployment (i.e. a large working class) and even a shortage of skilled labor. But despite persistent economic growth, major contradictions were brewing in society related to the dissatisfaction of the popular masses with the reactionary regime of De Gaulle, based on armed structures, the unresolved issue of education, the “problem” of immigrants and draconian orders in enterprises.

These acute contradictions, like a genie from a bottle of public patience, burst out in the days of May 1968. The clash between the warring classes broke out unexpectedly. At that time, global capitalism was selflessly reaping the benefits of unprecedented economic growth, achieved through the brutal exploitation of workers and depriving immigrants of basic living conditions. Growth in France began somewhat later than in other European countries, with the rise to power of General Charles De Gaulle in 1958. By 1968, economic growth had reached 5%. But these processes could not last forever, and entailed a deepening of class contradictions.

The foundations of the brilliant boom had been seriously corroded by the early 1960s. The rapid expansion of French goods on the world market led to 45% inflation in ten years, with price increases intensifying especially by 1968. Since 1960, the number of unemployed has increased by 70% (and a quarter of them were school graduates, university graduates and students who had not completed their studies). Already meager investments in healthcare and social services were cut. security. Infant mortality was higher than in other European countries.

3 million Parisians lived in houses without amenities, half of the housing was not equipped with sewerage. Factories practiced overtime, often while maintaining low wages. 6 million lived below the poverty line. Before the war, the Popular Front government introduced a 40-hour work week in 1936, but by the mid-1960s it was already 45 hours or more. Living conditions for immigrants were no better than in the Third World. If someone did not want to put up with this, employers easily got rid of them, depriving them of permission to work in the country with the help of the police. Factory dormitories were overcrowded, people lived in unsanitary conditions under the weight of fascist discipline - no guests, no newspapers and even no conversations while eating!

All this perfectly explains why France exploded like a powder keg. The acceleration of the pace of industrialization led to a high concentration of labor locally. Capitalism has produced its own gravediggers.

STORMING THE SKY

After long months of unrest and occasional conflicts, the revolution broke out like a bolt from the blue. In the very first days of May, the strike struggle launched by workers of various enterprises intensified and radicalized.

On May 1, one hundred thousand people took to the streets of Paris to celebrate workers' solidarity. Raising their fists, the youth chanted: “Work for the youth!” Workers from a variety of industries took part in the demonstration. Demands for a 40-hour workweek, trade union rights, and the repeal of the latest Social Security abolition order were everywhere. On May 3, printing workers threatened to strike. Parisian bus drivers held a spontaneous strike against increasing the working day; as a result, in one of the suburbs there were 10 buses instead of 180. On May 5, 569 workers left the sugar factory workshops. On May 6, taxi drivers and postal workers announced their readiness to join the strike.

The next day, police unions (!) discuss their demands and propose holding an action on June 1st. In Corsica, young agricultural workers begin to take over enterprises. Air traffic controllers are threatening to go on strike. At the Berlier automobile plant, strikers defend the payment of bonuses for 24 hours. The unions of metallurgists in Horteni, who have been on strike for a month now, are discussing their demands and have been blocking one of the national highways for an hour. The foundry is in the hands of the strikers; The garment factory is occupied by female workers for a week's time.

In western France, demonstrations were attended by energy workers, transport workers, machine builders, fishermen, postal workers, builders, teachers, and school students. On May 8, the following people took part in the demonstrations: in Brest - 30 thousand people, in Quimper - 20 thousand, in Rouen - 10 thousand, in San Briec for the first time since liberation a 10 thousand people demonstrated, in Morlaix 12 thousand took to the streets ., in Angier and Nantes - 20 thousand, in Le Maje - 10 thousand.

A powerful wave of the labor movement picked up and swirled in its stream the leaders of various parties and trade unions. The behavior of the authorities—university administrations, ministers, and police—only aggravated the situation and increased anger and indignation. Of particular note is the police, famous for their fascism and brutal behavior towards protesters. The police were swarming with reactionary elements who harbored hatred for the progressive intelligentsia, communists, trade unionists - everyone who, in their opinion, “sold out France and its colonies.” Racism was rampant among the police, manifested in the brutal persecution of Indo-Chinese and Algerians during the massacre of immigrant demonstrations in Paris.

After De Gaulle came to power in 1958, secret “committees of public safety” were created in the Paris prefecture. Also, units of the semi-military, semi-independent organization - the Civil Action Service (SRS), established by the Gaullist party, were distinguished by particular atrocities. Members of the SRS demanded that they be given helmets and batons in order to participate in storming the barricades on the side of the police and neo-Nazis.

The anger and resentment gradually accumulating in French society was caused in large part by the actions of the state machine of suppression. Not a single segment of the population remained unaffected by the repressions. The behavior of the government, the disgusting DeGaulle manner of ignoring the crisis, the very barracks language of De Gaulle - all this pushed people to openly express their indignation, nurtured over many years of tyranny and “personal power”.

Along with the working class, students and schoolchildren played one of the leading roles in the 1968 revolution. As early as the early 1960s, French students were involved in a large movement against the Algerian War. They supported the struggle for Vietnamese independence no less decisively.

In early 1968, students made themselves known by demanding the abolition of numerous restrictions and outdated rules in the education system. This protest escalated into open clashes with police on the streets of university campuses.

Each blow from the police increased the anger and determination of the students. On May 6, the police brutally dealt with a 60,000-strong student demonstration in the Latin Quarter of Paris. In defense, the students began to build barricades using whatever they could get their hands on.

The police retreat was always accompanied by thunderous applause from the spectators on the balconies. Parisians supplied the demonstrators with food and radios and hid them in their apartments.

The simultaneous impulse of the labor and student movements led to an even more rapid growth of mass protests.

Corrupt trade union leaders, famous for their opportunism, under pressure from the ranks, finally decided to go on a one-day strike. They hoped that a 24-hour strike would pour out the main indignation and life would return to normal. French trade union leaders often carried out such actions aimed at dissipating and relaxing the energy of the working class at a time when it was ready for serious struggle.

But, despite the tricks of the social henchmen from the pro-revisionist trade unions, the general strike on May 13 was not limited to 24 hours. It turned into a grandiose demonstration of workers' solidarity and had a huge impact on the consciousness of the proletarian masses. Imagine, on this day 1 million people took to the streets of Paris, 50 thousand in Marseille, 40 thousand in Toulouse, 50 thousand in Bordeaux, 60 thousand in Lyon.

In Paris, the demonstration reached such a scale that the police were forced to stand aside. The banners called: “Students, workers and teachers - unite!” Red flags were flying everywhere and the singing of the International could be heard. This grandiose action helped the workers realize the full power and invincibility of their strength.

The General Assembly of the Sorbonne rebels gathered more than 5 thousand people in the amphitheater every night. Soon almost all French universities were in the hands of students. The students showed miracles of courage and resourcefulness. They organized special teams to build barricades, to help the wounded, to transport mail on motorcycles with red flags, etc.

The “iron battalions” of the industrial proletariat at this time were ready to enter the battle and carry with them new layers of society that did not yet have experience of struggle. The students, along with the intelligentsia, have already made a preliminary maneuver, made the first gap in the ranks of the enemy, but it is impossible to bring the matter to final victory without the army of the proletariat.

After participating in the protest on May 13, the workers were deeply impressed by the whole event and, a few days later, and in some cases a few hours, they again entered the battle, challenging the right to govern the country.

De Gaulle did not make any statements at this time, and demoralized by what was happening, he did not know what to do. However, he nevertheless decides not to postpone the already planned official visit to Romania - as if nothing had happened. Shortly before this, De Gaulle called the Soviet Union (by that time pretty much eaten away by the worms of Khrushchev’s revisionism and Brezhnev’s social-imperialism) “the stronghold of Europe.” Apparently, he and the Romanian leader Ceausescu will calm each other down in the face of the danger of a storm that could sweep both one and the other off the face of the earth.

The general strike was well advanced even before De Gaulle returned to France. Student protests and mass demonstrations of workers have broken the dam: the movement has begun and cannot be stopped. On May 15, strikes and occupations by factory workers covered Renault car factories, shipyards, hospitals, as well as the Odeon national center.

Red flags were flying everywhere. At the Orly-Nord airport repair plant, daily rallies and meetings of the strike committee were held, attracting several thousand people every morning. The strictest discipline was observed, the need for which everyone understood, and the equipment was looked after even better than usual.

By May 16, the ports of Marseille and Le Havre and Veldance were closed, and the Trans-European Express interrupted its route in the south of France. Newspapers were still published, but printers exercised partial control over what was printed. Many public services functioned only with the permission of the strikers.

FRUITS OF THE REVOLUTION

French Prime Minister Pompidou said in a televised speech: students should not listen to agitators, and citizens should not succumb to anarchy. But there was no anarchy in the factories. Calm and order reigned there. The factories taken under workers' control turned not into anarchic gatherings of idlers, but into a kind of citadel of Bolshevism.

Pompidou was left alone “De Gaulle in Romania headed the government in exile,” Parisians joked. Like a ghost, returning to his homeland on May 19, De Gaulle found himself a miserable prisoner of the Elysee Palace. Cells of new proletarian power - action committees - gradually began to be created in the country. In essence, a dual power has developed. On the one hand, there is the demoralized and hated old state machine, which all that remains is, in Lenin’s words, to be smashed. On the other hand, the bodies of workers', peasants' and students' self-government that emerged in the battles are cells of proletarian democracy looming on the horizon.

Hundreds of action committees of various enterprises, institutions, universities, schools, neighborhoods felt the need for cooperation and reached out to each other. For example, in the Loire-Atlantique department, workers, peasants and students made all their decisions together. In the center of the department - Nantes, the Central Strike Committee took upon itself the control of traffic at the entrances and exits from the city.

Roadblocks erected for this purpose by transport workers were operated with the help of schoolchildren. This desire of the people to establish their own order was so irresistible that the city authorities and police had to close their eyes and meekly retreat. At one of the factories, an unprovoked police attack, threatening inevitable casualties, ended... in fraternization.

Factory workers took control of the supply of local stores with food and the organization of various retail outlets in schools. Workers and students organized trips to farms to help peasants plant potatoes.

Having expelled intermediaries (commission agents) from the sales sphere, the new revolutionary authorities lowered retail prices: a liter of milk and a kilogram of carrots now cost 50 centimes, instead of 80, and a kilogram of potatoes - 12 instead of 70.

To support families in need, unions distributed food coupons to them. Teachers organized kindergartens and nurseries for the children of the strikers. Energy workers have undertaken to ensure an uninterrupted supply of electricity to dairy farms. We ensured regular delivery of feed and fuel to peasant farms. The peasants, in turn, came to Kant to walk shoulder to shoulder along the streets with workers and students.

Real improvements in the lives of the masses oppressed by capitalism were more convincing than the most eloquent political speech.

When the working class, straightening its back, stands up to its full height, raising its million-strong battalions for the class struggle, it becomes clear who has real and indestructible power in society, then the broadest sections of the population begin to move. The farmers who entered the struggle made strong demands and backed them up with actions.

All new warehouses and estates pass into the hands of the strikers. Lawyers organized their actions. They, like all civil servants, were concerned about their role, if any, in a socialist society. 200 museum curators came from all over the country to discuss the role of museums in society, and their subordinates, carried away by the general impulse of national renewal, began to critically review the old-fashioned, ineffective, overly centralized management of museums.

Architects and urban planners believed in the quick realization of their secret dream - that their talents and abilities would serve the whole of society, and not the wealthy minority. Hospitals switched to self-government; committees of doctors, patients, trainees, nurses and orderlies were elected and operated in them.

Just as a rainstorm irrigating the desert causes the rapid growth and flowering of exotic plants, the revolution prepares the flowering of the most bizarre and temptingly beautiful ideas in the field of fine art, music and literature. The contours of how culture can flourish if the shackles that subordinate everything to capitalist profit are broken are becoming visible.

A group of writers seized the headquarters of the Society of Writers. The general meeting of the newborn writers' union put on the agenda the question of "the status of the writer in a socialist society." Filmmakers have developed a whole program for updating the film industry. The principles set out in it were in line with the planned socialist economy. Artists imbued their works with social meaning and exhibited them in huge galleries - workshops of automobile and aircraft factories. Actors performed performances at striking factories. Opera singers demanded independent control of their genre.

It was an unforgettable experience for everyone, when the rigid framework of life in a capitalist society seemed to be forever broken, when people were seized by a general spirit of condemnation of the capitalist order that reigned in society.

REVISIONISTS - MINIONS OF REACTION AND STRANGELLERS OF REVOLUTION. LESSONS OF DEFEAT

How did the events in France end in 1968? If the general strike had developed in full force, the victory of the revolution would have become inevitable not only in France, but throughout Europe. No matter how strange it may seem, the main reason for the defeat of the 1968 revolution was the indecision of the leaders of the labor movement to go to the bitter end. And the main role here was played by the capitulatory position of the most influential among the working class, the French Communist Party (PCF).

“It is known how the fate of the French Communist Party developed; it decisively took the revisionist path. She betrayed Marxism-Leninism, nuancedly pursued and continues to pursue the Khrushchev-Brezhnev line” (E. Hoxha).

From the very beginning of the mass protests, the PCF and the top of the trade unions controlled by it (the General Confederation of Labor - CGT), in one voice with the official policy of the social-imperialist USSR, condemned the rebels, declaring that “leftists, anarchists and pseudo-revolutionaries” were preventing students from taking exams!

And only by May 11, the PCF “understood the situation”, calling on workers for a one-day strike of solidarity with students under the slogan “End repression!”, and by the end of the month the authorities “were lying under their feet.” However, the “traditional communists” (more precisely, their elite, something like the Communist Party of the Russian Federation) refused decisive action, considering the situation in the country “pre-revolutionary”.

Trade union and Communist Party leaders, calling for a one-day strike on May 13, hoped that it would “vent the main indignation, let off the steam” of discontent, and life would return to normal. However, as we have seen, this did not happen and the general strike on May 13 was not limited to 24 hours.

French trade union leaders at that time often erred in their intentions to disperse and disperse the forces of the working class at a time when it was ready for serious class battles. The emerging situation in the country increasingly urgently demanded from the party and trade union leaders of the working class a clearly coordinated militant, revolutionary program of action.

Instead, the revisionist leadership of the Communist Party and trade unions dragged their feet and constrained action with their demagogic statements. General Secretary of the CGT Georges Séguy generally told the Renault workers: “Any call for an uprising can change the nature of your strike!” These words were aimed at cooling the red-hot steel of the class struggle. Prime Minister Pompidou, in his speeches, spoke in much the same spirit as the revisionists, calling for “calm.”

The May movement of 1968 was interpreted by the revisionists purely as a struggle for higher wages and improved working conditions, recognizing only the economic struggle. But the economic struggle will not bring complete success if it is not associated with the socialist reorganization of the world. Without organizing the revolutionary struggle of the workers into a single anti-capitalist impulse, the revisionists extinguished the next wave of the all-purifying flame of the socialist revolution.

Despite the assurances of the PCF, the revolutionary situation in France in 1968 developed. Firstly, the ruling class, faced with a general protest movement, was paralyzed and, as a result, split into various factions. Secondly, the protests of the proletariat aroused the middle strata to fight, in whose ranks ferment began. Thirdly, the working class was quite determined. He looked for a way out of the crisis using the most radical, revolutionary (and therefore the most correct!) methods. And fourthly, the workers had a wide and extensive network of their organizations, as well as an influential Communist Party.

That. all four factors for the victory of the revolution seemed to be present. However, it was the fourth and fundamental factor that was not entirely real. Trade unions and the Communist Party had influence, but did not organize the struggle for socialism. They limited themselves to economism, thereby cooling the intensity of the struggle necessary for complete victory.

The pro-Moscow revisionists did not need a revolution; in general, they already had a good position: seats in parliament, formal legality, recognition among the masses. One of the newspapers wrote: “The last thing the Kremlin wants is a revolution in France, which would deprive Russia of significant support coming from the foreign policy of General De Gaulle.

So, let's return to the May events. The height of performances. The government is out. De Gaulle, paralyzed by the events, gave a speech on the radio in which he “admitted” that the share of the French people in governing society was negligible. But all he could “offer” was a referendum on the “forms of participation” of ordinary people in governance.

The policy of “concessions and reconciliation” on the part of the ruling class was unable to dispel the wave of popular protest. Convinced of the “seriousness” of the intentions of the oppressed masses on the one hand and of the indecisiveness of the workers’ leaders on the other, the government decided to return to its usual tactics.

Result: the night of May 25 ended like “Bloody Friday”; a night of police violence in many cities. Against the backdrop of the unfolding tragedy, the revisionists and the top trade unions controlled by them, showing their opportunistic nature, agreed to an agreement with the government. At this time, a “decisive meeting” was taking place on Rue Grenelle. It seemed that trade union leaders and members of the government were the only ones who wanted the unrest to stop and the movement to fade away.

In such a situation, even the least amateur could come to an agreement with the government on the most favorable terms. The revolutionary threat hanging over the capitalists made it possible to extract concessions that were impossible to achieve over many years of disputes and negotiations. A class facing its doom will draw the last of its supplies to pacify the enemy and buy time, and then, when the storm subsides and the enemy leaves the battlefield, will find an opportunity to compensate for the losses.

Having achieved concessions, the revisionists “achieved” a decline in the movement, a further onset of reaction, the strengthening of capitalism, etc. As a result, De Gaulle declared that “there will be no referendum,” dissolved parliament and called new elections, to which the “communists” also rushed.

SHORT CONCLUSIONS

Why did Red May fail? It is probably worth first asking the question why the workers followed the revisionists. The answer lies in the influence of Khrushchev-Brezhnev revisionism among the international labor movement of that time. The workers saw power and example in the USSR. But after the death of Stalin, the USSR became a stronghold of opportunism unleashed by the cliques of Khrushchev and Brezhnev.

The workers did not understand the essence of internal political processes in the USSR and pro-Soviet states. For them there was a concrete example of the highest freedom and justice - precisely the “socialism” that existed in these countries. Unfortunately, it was the revisionism of Khrushchev-Brezhnev that began to dominate in many large and influential communist parties in Europe, and, perhaps, in most countries of the world. And revisionism, as we have already seen, is the main reason for all the defeats of the working class.

Any revolution is preceded by ideological argumentation and preparation. The “May Revolution” of 1968 is undoubtedly no exception. Why is there special interest in the events of 1968 today? Today, social and global divisions are getting worse every year. Large numbers of people are unemployed or have low-paying and unstable jobs. In Eastern Europe and Asia, vast armies of workers are exploited for meager wages. The result of growing contradictions will inevitably be new conflicts. This is the main reason for the current interest in the 1968 protests.

What happened in 1968? France was then riddled with deep contradictions. Under the impenetrable political regime of the 68-year-old president, General de Gaulle, a rapid economic modification took place that radically changed the social structure of French society.

After the end of the Algerian War in 1962, the French economy was rapidly gaining momentum, which resulted in low unemployment and even a shortage of skilled workers. However, such growth required investment in production and technology development, so new industries were created that successfully compensated for the decline in the production of coal mines and other old industrial sectors. New enterprises were created in the automotive, aviation, space, defense and nuclear industries. At the same time, financing of the social sphere, primarily health care and social security, lagged behind. 3 million Parisians lived in houses without amenities, half of the living quarters were not equipped with sewerage, 6 million citizens of the country lived below the poverty line. In factories, workers had to work overtime, often while maintaining low wages. By the mid-1960s, the workweek had increased to 45 hours. Living conditions for immigrants were little better than in the Third World; workers' dormitories were overcrowded and completely unsanitary.

The living and studying conditions of students have become relatively worse. State expenditures on education increased, as the development of new industrial sectors required replenishment with new labor resources, but due to the demographic boom of the post-war years, it became more difficult for people from low-income families to obtain higher education. As a consequence, higher education institutions were overcrowded, poorly resourced, and under government surveillance. Opposition to such unsatisfactory learning conditions and the anti-democratic regime at universities (communication between boys and girls outside of school hours, namely visiting dormitories of the opposite sex, was also prohibited) became the main factor in the radicalization of students. In addition, political issues were quickly added to this.

Also in 1967, the global recession also took its toll on workers. For a number of years, the standard of living of workers and their working conditions lagged behind the pace of development of the country. Salaries were low, the working week was long, all this was accompanied by lack of rights for workers at enterprises. Now unemployment and long working hours have been added. The mining, steel, textile and construction industries entered stagnation. Farmers also began to protest against the decline in income, even leading to street battles with the police.

By the beginning of 1968, the country, at first glance, seems to be a relatively balanced state; at the same time, social tension is growing and heating up. France resembles a powder keg - all that is needed is a spark, which is the student protests.

It all started at the University of Nanterre, one of the new educational institutions that was built in the 1960s. On January 8, 1968, students publicly expressed their outrage at the visit of Youth Minister François Misoff to the city to inaugurate the swimming pool. The incident itself was of little significance, but the sanctions imposed on the students, as well as the systematic intervention of the police, caused an increase in student disobedience and turned Nanterre into a hotbed of a revolutionary movement, which quickly spread to other universities and high schools throughout France. The protesters demanded improved study conditions, free access to universities, personal and political freedom, and the release of arrested students. Thus, from February to April 1968, about 50 major student protests were carried out in the country. And on March 22, students seized the administration building of the University of Nanterre. In response, the administration completely closed the university for a month, but the conflict spread to the oldest university in France, the Sorbonne.

The 22 March Movement was based on the ideology of the so-called Situationist International led by Guy Debord. The Situationists believed that the West had already achieved a commodity abundance sufficient for a communist system, and the time had come to organize a “revolution of everyday life.” This meant refusal to work and subordination to the state, refusal to pay taxes, comply with laws and public moral norms. On May 3, representatives of various student organizations gathered to discuss the issue of carrying out this protest campaign. The dean demands the police to "clean up" the campus. As a result, a large demonstration spontaneously gathers. The police are being extremely harsh and the students have responded by setting up barricades. As a result, by the morning about a hundred people were injured, several hundred were arrested. The court handed down severe punishments to 13 demonstrators. In turn, in response to this, students created an “anti-repression defense committee”, and junior teachers called for a general strike in higher education institutions.

Information about the events that took place was instantly transmitted by radio stations, and residents of the country were agitated by the brutality of the police. In Paris, demonstrations are becoming larger every day and are already spreading to other cities with calls for condemnation of police repression and the release of arrested students. Thus, on May 6, demanding the release of convicts, an end to police violence, the opening of the Sorbonne and the resignation of the rector and even the minister of education, 20 thousand protesting students, teachers, lyceum students, and schoolchildren came out to demonstrate. To the applause of the population, the column walked freely through Paris with a banner “We are a small bunch of extremists,” as the authorities called the students the day before. But upon returning to the Latin Quarter, the demonstration was suddenly stormed by six thousand police. Young people from all over Paris came to the rescue of the students, and by night the number of street fighters reached 30 thousand, of which 600 people were injured, 421 were arrested.

The movement quickly gained momentum. Strikes and demonstrations by students and various workers and employees spread throughout the country. By May 7, all universities and the bulk of Parisian lyceums were already on strike. When 50 thousand students came out to the next demonstration in Paris demanding the release of their convicted comrades, the withdrawal of the police from the territory of the Sorbonne and the democratization of higher education, the authorities expelled all participants in the unrest from the Sorbonne. It was the evening of May 7 that became a turning point in public opinion. The protesting students were supported by almost all trade unions, teachers, teachers, scientists, as well as the bourgeois French League of Human Rights. As a result, on May 8, in a number of French cities, amid the singing of the International, the first general strike took place under the slogan “Students, workers and teachers - unite!” . In Paris, such a large number of people took to the streets that the police were forced to stand aside and not intervene. However, the police brutally stopped the convoy’s attempt to reach the buildings of the Television Administration and the Ministry of Justice by firing grenades with tear gas. Retreating under the pressure of special riot control units, students set fire to the cars from which barricades were built. The whole city knew that mass student unrest had been taking place at the Sorbonne since the beginning of May, but no one thought that the matter would take such serious consequences. Correspondents broadcast reports from the scene directly on air, and on the morning of May 11, newspapers came out with huge headlines: “Night of the Barricades.” As a result of the students' long night resistance to the police, 367 people were injured, including 32 seriously, and 460 were arrested. . This was the beginning of a general political crisis in the country, despite Prime Minister Georges Pompidou’s speech on radio and television promising to lift the Sorbonne lockout and review the cases of convicted students. Alas, it was already too late - the political crisis was rapidly gaining momentum.

On May 13, trade unions called on workers to support the students, as a result of which the country was paralyzed by a 24-hour general strike. Almost the entire working-age population took part in it - 10 million people out of a total of 15 million. The call for a strike finds a large response - in large provincial cities such as Marseille, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Lyon, etc., demonstrations of solidarity by thousands were held. In Paris alone, 800 thousand citizens took to the streets with political demands, even calling for the overthrow of the government. Immediately after the demonstration, students seized the University of Strasbourg and the Sorbonne, declaring the university “an autonomous people's university, constantly open 24 hours a day to all workers.”

The trade unions' plan to limit the strike to one day failed. On May 14, workers occupied the aircraft plant of the Sud-Aviation company in the city of Nantes, which led to a chain reaction: workers began to seize hundreds of enterprises, plants, factories throughout the country, covering almost all sectors of the heavy industry. industry. The Renault automobile plant in Biyancourt was also among the “staffed” enterprises.

At the same time, students captured the university one after another. The number of large enterprises seized by workers reached fifty by May 17. On May 20, France, gripped by a general strike, stops, although neither trade unions, nor parties, nor other organizations called for it. Journalists, football players, artists - everyone is joining the protest movement. The entire country was paralyzed, from government institutions to schools. In 1968, 150 million workdays were lost due to long strikes, according to the Department of Labor. By comparison, the 1974 British miners' strike that forced the resignation of Edward Heath's Conservative government resulted in the loss of 14 million working days.

The wave of strikes does not subside until July, but reaches its peak between 22 and 30 May. On May 20, the government effectively lost control of the country. The population is calling for the resignation of de Gaulle and his government. At the National Assembly, the issue of no confidence in the government was accepted for discussion, but only one vote was missing for a vote of no confidence. Then, on May 25, tripartite negotiations began between the government, trade unions and the National Council of French Entrepreneurs. Conditions were agreed upon for a significant increase in wages, but the General Confederation of Labor (CGT), represented by Georges Séguy, was not satisfied with these conditions and continued the strike movement. Socialists led by François Mitterrand organize a grand rally to condemn the trade unions and de Gaulle and demand the creation of a Provisional Government. In response, authorities in many cities are using force. The night of May 25 was called “Bloody Friday.”

On May 29, during an extraordinary meeting of the cabinet of ministers, it became known that General de Gaulle had disappeared without a trace. France is in shock. The leaders of “Red May” immediately call for the seizure of power, since it is allegedly “lying on the street.” However, on May 30, de Gaulle reappeared and made an extremely harsh speech, announcing the dissolution of the National Assembly and the holding of early parliamentary elections. The Gaullists organized a campaign to threaten a communist conspiracy, and as a result, having received a majority of seats, the frightened middle class unanimously voted for the general. On the same day, the Gaullists hold a 500,000-strong demonstration on the Champs-Elysees in support of de Gaulle. There is a radical change in events. In early June, unions held new negotiations and achieved new economic concessions, after which the wave of strikes subsided. Enterprises seized by workers are beginning to be “cleaned up” by the police. Cohn-Bendit was exiled to Germany. On June 16, the police seized the Sorbonne, and on June 17, the work of the Renault conveyors was resumed.

Thus, the “May Revolution” was defeated. Then why did she become legendary?

Firstly, because in May 1968, during an economic recovery (not a crisis!), from an insignificant incident in Nanterre, for the first time in Western history, a national crisis developed instantly and with lightning speed, developing into a revolutionary situation. This made it clear to many that the social structure of European society had changed.

Secondly, because the unrest of 1968 changed the moral and intellectual climate both in France and in Europe as a whole. Alexander Tarasov substantiated this in his article “In memoriam anno 1968”, in which he wrote that “until the advent of neoliberalism and the “neoconservative wave” of the early 80s, being right and loving capitalism was considered indecent. The first half of the 70s, overshadowed by the glow of “Red May,” turned out to be the swan song of the European intellectual and cultural elite. Everything worthwhile in this area, as the West sadly admits today, was created before 1975–1977. Everything that comes later is either degradation or rehashes...”

In turn, the students achieved the democratization of higher and secondary educational institutions, the permission of political activity on university and college campuses and an increase in the social status of students, as well as the damage to the reputation and image, and subsequently the resignation of de Gaulle. Moreover, the “Orientation Law” was adopted, coordinating the actions of universities with the immediate requirements of the economic situation in the country, thus reducing the risk of unemployment for graduates. The psychological “wall” between students and the working class was also destroyed, albeit temporarily.

What prompted such a huge collective struggle to involve such a huge number of people of various ages, professions, social status, etc.? “But it was here, in a modern country, with millions of people participating, learning that it was possible to live like a human being. This was the essence of the demands that adorned the walls of the Latin Quarter. They questioned the way we lived, condemned the madhouse in which we live,” recalled Roger Smith, a participant in the events of 1968.

“Red May” was undoubtedly one of the most striking and significant events that was a consequence of phenomena and changes at the present time. The world has become different. Speaking at the University of Montreal 40 years after the events of 1968, Daniel Cohn-Bendit admitted: “That spring did not fulfill its revolutionary promises, but it influenced the expectations and behavior of many people, since it opened up for them an unprecedented individual freedom.”

Bibliography

- Kara-Murza, S. G. Export of revolution. Yushchenko, Saakashvili... [Text] / S. G. Kara-Murza. – Algorithm, 2005. – 528 p.

- Kara-Murza, S. G. Alexandrov, A. A., Murashkin, M. A., Telegin S. A. On the threshold of the “orange” revolution [Electronic resource]: prepared. to ed. - Electron. Dan. Access mode: http://bookap.info/psywar/orangrev.htm, free. - Cap. from the screen. - Yaz. rus.

- Shwarz, P. 1968: General strike and revolt of students in France // Peter Shwarz // MCBC, 12 th of May, 2008

- Kara-Murza, S. G. Revolutions for export [Text] / S. G. Kara-Murza. – Eskmo, Algorithm, 2006. – 528 p.

- Skhiviya, A. Red May – 68 [Electronic resource]. – Access mode: http://www.revolucia.ru/may68.htm (date of access: 04/09/2015)

- Tarasov, A. In memoriam anno 1968 [Text] / A. Tarasov // “Zabriskie Rider”, 1999. – No. 8.

- Smith, R. May-June '68 [Electronic resource]. – Access mode: http://www.revkom.com/index.htm?/naukaikultura/68.htm (access date: 04/09/2015)

- Dubin, B.V. Symbols - institutions - research: New essays on the sociology of culture [Text] / B.V. Dubin. - Saarbrucken: Lambert, 2013. - 259 p.

Let's not lie - none of us really understands '68, but we all live in its consequences. Everything that surrounds us - social, cultural and political reality, norms of sexual behavior, mass stereotypes, religious and quasi-religious beliefs, ideas about success in life, and whatever you take, even such a seemingly extraneous thing as advertising - all this was subjected to a total attack in the late 60s, total demolition and total rebuilding.

Red May 1968 in Paris

In 1968, a social cataclysm occurred on the planet, the exact definition of which historians are still in no hurry to define. Maybe 37 years ago there was a world social revolution. Maybe it's a cultural revolution. Perhaps it was “just” a revolutionary situation - but a situation that thoroughly shook the foundations of the world order. For brevity, we will simply say “68th”.

On the eve of 1968, the world looked completely different from what we are used to now. Education remained a class privilege: access to universities for children of the lower classes was almost closed. The curriculum was archaic and far removed from life. In universities - and in the big world too! - hypocritical morality reigned, the very concept of sexuality was beyond the scope of discussion, it was taboo, forbidden. The Church remained the main moral authority, at least at the level of the family and family education. In many countries, openly reactionary dictatorships were in power (as in Spain, Portugal and Greece), or reactionaries - even former fascists - constituted a significant and often leading stratum of bureaucrats and politicians in countries that were formally democratic (as in Germany). The very spirit that reigned in society was heavy, pernicious and somehow hopeless... Well, you know, something like in Russia after Nord-Ost. Only European and North American youth could no longer endure it. She wanted to breathe - and she blew up the cramped little world prepared for her by her parents and suitable only for rotting alive.

The events of 1968 acquired their greatest scope and greatest symbolic significance in Paris (although rallies, demonstrations, strikes, and seizures of universities and factories occurred not only throughout Europe, but throughout the world).

Thunder sounded practically in the middle of a clear sky. A few weeks before the events began, a sociological analysis entitled “France is sleeping” appeared in the press. In this seemingly sleepy environment, a group of leftists attacks the Paris office of the American Express Company in protest against the US war in Vietnam. Six attackers have been arrested. Two days later, on March 22, 1968, in Nanterre, a suburb of Paris, students seize the university administration building, formally in order to demand the release of those arrested. But the matter is not limited to this: during the stormy meeting, more and more new demands are put forward. The situation is electric for various reasons. Let's say, exactly the day before, on March 21, students in Nanterre refused to take an exam in psychology - as a sign of protest against the monstrous primitiveness of the course taught to them. To coordinate actions, the anarchist “March 22 Movement” was immediately created here, which played a significant role in the further escalation of events.

Actually, the events in Nanterre turned out to be a trigger, only the authorities did not know this yet and therefore responded as usual: with brutal repression. As the “March 22 Movement,” despite pressure from the authorities, expanded (the slogan “From criticism of the university to criticism of society!” was put forward), the government increasingly used the police. Events developed like a snowball - the conviction of a group of instigators - the closure of the university - new clashes between students and the police - new arrests - new demonstrations - new clashes - new arrests - new demonstrations...

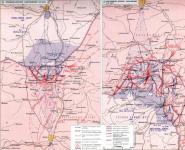

STREET FIGHTING IN PARIS

Red May slogans in Paris

By May 10, 1968, the number of those injured during clashes on the streets of Paris exceeded a thousand, and the number of those arrested, too. Not only students, but also most teachers, prominent cultural figures and Nobel laureates, the largest trade unions and left-wing parties demanded that the police be curbed. But French President General de Gaulle stood like a rock, declaring that he would not give in to the youth. On May 10, a 20,000-strong student demonstration was blocked on both sides by French riot police on the Boulevard Saint-Michel. Unfortunately for the authorities, the boulevard was paved with cobblestones and by nightfall the students had erected about 60 barricades - not only paving stones were used, but also cars parked nearby, in general, everything that could impede the advance of special police units. The battles on the barricades continued until six in the morning.

On May 13, students began to seize universities in the largest cities of the country, and from May 14, workers began to seize factories, without any sanction from trade unions and traditional left parties, moreover, to their panicky horror. On the 15th, the Odeon Theater was captured by students and turned into a discussion club. The walls of the Latin Quarter were covered with numerous posters and graffiti. The most famous slogans of the Parisian Red May: “It is forbidden to prohibit!”, “Be realistic - demand the impossible!” and “Imagination to power!” But, in addition: “Under the pavements there are beaches”, “The border is repression”, “You cannot fall in love with the increase in industrial production”, “Everything is fine: twice two is not four”, “Orgasm - here and now!” Of course, this did not fit into the usual concepts of the traditional leftists who had chosen their positions over the two and a half post-war decades. But it smacked of thinking in the spirit of the Situationist International, which was one of the main intellectual provocateurs of revolutionary events.

ON THE ROLE OF REBELING INTELLIGENCE AND PLAYING SELF-AWARENESS

A small group at the intersection of politics and art (let us remember, in order to avoid harmful confusion, the words of Walter Benjamin that the left responded to the aestheticization of politics by the fascists by politicizing art. Let us remember and do not forget - this is important), which arose in the late fifties on the ruins of Dadaism, surrealism and radical political leftism of the mid-20th century, was few people knew until the cast-iron head of world capital was struck by the Indian tomahawk of the 1968th. There were only a few of them (according to another version, still several dozen people), and, in addition to practicing art, they, more importantly, published the yearbook “Situationist International”, in which the theoretical gift of Guy Debord and Raoul Vaneigem was fully demonstrated , the authors of two books that are most important for understanding the modern revolutionary process, respectively - “The Society of the Spectacle” (also translated as “The Society of the Spectacle”) and “The Revolution of Everyday Life”.

To put it briefly (to reduce tons of worldly wisdom, translated by the Situationists into kilograms of printed text, to milligrams of an extract, “leaf tea”, which is always with you, under the lid of a teapot called a “skull”), then they believed that modern capitalism has learned to transform any facts life, be it a sincere emotion of love or a fierce outburst of protest - into a spectacle, and the spectacle - into a product, which, being packaged into television news releases, selections of advertising videos, into habits and moods imposed through the media, loses any features of its primary, " pre-sale authenticity, and at the same time all the signs of danger to the prevailing economic, ideological and political order. Therefore, the Situationists believed, for a true revolutionary there is little use in creating large political parties, even the most radical ones, or in the long and difficult formation of trade unions, even the most fighting ones - all these institutions can no longer be instruments of rebellion, instruments of revolution.

The instrument of rebellion can only be each individual human personality, as well as voluntary unions of these individuals, formed for the only truly fun and truly liberating human game - the revolution of everyday life. In a word, no party will help you, no Komsomol, no trade union, no fucking shit terrorist organization. Only myself. Only with your head. Only through your own effort. Only in your own life.

Now we’ll re-read: “You can’t fall in love with the growth of industrial production”, “Orgasm - here and now!” Sounds a little different, doesn't it? However, enough theory here (those who suffer, don’t miss the upcoming “Anthology of the Situationist International” or look for Ken Knabb’s book “The Joy of Revolution” now, online or in a bookstore).

1968: THE RISE OF MEANING

Let's return to Paris, France. A national crisis was raging in France. Flashed out of thin air? From any one leftist action? From one brave act of students who captured the dean's office? Out of the stupidity of the Minister of Education? From the stubborn insanity of Mr. President? Yes, from all this, but also from the fact that the old world has ceased to withstand new meanings, new impulses of life, its hot breath, its feverish sparkle in the eyes.

This is what film director Hélène Chatelain, who recently made a film about “our” Stalin’s Gulag, and then, in ’68, was a Parisian student, recalls: “...The explosion that occurred then was an explosion within the meaning. The main question was not “how.” organize a movement?", but "why?" and "what does it mean?" It was a deep semantic explosion. The political language was absolutely not adapted to the situation that arose. It turned out to be outside the framework of what the people who spontaneously took to the streets wanted to say. (...) Only later, when the trade unions saw that all the factories in France had stopped (which seemed impossible and incredible to them!), they began to formulate demands. After all, it is impossible to answer the question: “What do you want?” - answer: “We we want to live,” “We don’t know what we want.” That’s when the trade unions started fussing: “We want more wages,” and then all this went into “normal trade union activity.”

"Where will you go? Where will the demonstration go?" - the intimidated authorities asked student leader Daniel Cohn-Bendit at the peak of the movement. "The route of the demonstration will depend on the direction of the wind!" - a young impudent man with fiery red hair answered them, not without a pose. And at the same time he was absolutely, one hundred percent, mathematically accurate. For this was the only way in May 1968 that it was possible to voice “the phrase that the street was writing.”

EASTERN EUROPE WAS ALSO STORMING

'68 would not have been what it was if the events, no matter how grand, beautiful and inspiring they were, had only taken place in France. 68 (we agreed at the beginning that this is a comprehensive, complex term, and not just a compound numeral) spread widely on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

I would like to talk about everyone, but there is no space, I will only name the countries and maybe some milestones.

In Czechoslovakia - Prague Spring. Society, which has long been ready to explode, reacts to the slightest changes in the course of the party leadership and, without waiting for a command from above, begins to free itself on its own. They moved from words to deeds, however, already in parallel with the beginning of the Soviet occupation. In Czechoslovakia, there were also seizures of factories, there were also crowds of people against tanks on the streets, for some time there was even a second, underground leadership of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, there was even (think about it - in an officially socialist country!) an illegal congress (!) of the ruling (!!) communist party (!!!) - under the protection of workers, at one of the captured factories.

Then, as in Western Europe, there was a rollback. However, in 1968, times were not yet so leaden ("Times of Lead" by Margaretha von Trotta is a must see, although they are about another stage of the revolutionary movement in Europe; about 1968, or rather, about why 1968 happened) oh, look at the magnificent films of Jean-Luc Godard, first of all - “Weekend” and “The Chinese Woman”) - and that’s why young people rebelled, including in the East.

Poland. March '68. Student protests in Warsaw and Krakow, clashes with police, about 1,200 students were arrested.

In Yugoslavia - mass student demonstrations in June '68. The country's leader, Marshal Tito, is forced to move on to broad socio-political reforms (by the way, another important film for understanding the era was shot in Yugoslavia in 1968-71. This is “V.R. Secrets of the Organism” by Dusan Makaveev, in detail, to what extent this is generally perhaps in a feature film, expounding and illustrating the theory of the sexual revolution of this very V.R., that is, Wilhelm Reich (Reich died in an American prison in the late fifties, but his case inspired the rebels of '68).

IN TELEGRAPH STYLE: ALL OVER THE WORLD

Germany. Stormy student riots, occupation of universities, the emergence of new, outside the ossified leftist tradition, revolutionary associations (remember for searching on the Internet: “Commune-1”, “Socialist Collective of Patients”).

Italy. 95 percent of the country's population is on strike!

Vietnam. The famous partisan Tet offensive (the same one after which the child was named in the recent film “Together” by the Swede Lukas Moodysson - also watch, laugh and cry - about what the generation of ’68 became seven years after the revolution).

USA. A raging sea of events, it’s impossible to even list them all. I’ll just give you the scale: riots in more than 170 cities, 27 thousand people were arrested - these are several “divisions” of rebels!

And also: Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, Portugal, Israel, Japan, Spain, China...

WELL?

Lost again? It depends on how you look. If we consider the revolution of 1848 (forgetting about 1852) or the revolution of 1917 (forgetting about 1921) as a “win” - then maybe so. And if you turn off the cliches and turn on the imagination, which alone is worthy of power, then...

The 68th neither won nor lost. He shaped the world in which we now live. However, some believe that that era ended on September 11, 2001. Is it over? Let's see.

May events in France 1968.

M Ai events 1968, or simply May 1968 fr. le Mai 1968 - a social crisis in France, resulting in demonstrations, riots and a general strike. Ultimately led to a change of government and the resignation of President Charles de Gaulle.

The events of May 1968 began in Parisian universities, first on the campus in Nanterre, and then on the Sorbonne itself; one of the most famous leaders of the riots is Daniel Cohn-Bendit. The driving force of the students, in addition to the general youth protest (the most famous slogan is “Forbidden is prohibited”), were various kinds of extreme left ideas: Marxist-Leninist, Trotskyist, Maoist, etc., often also reinterpreted in a romantic-protest spirit. The general name for these views, or rather sentiments, is “gauchism” (French gauchisme), originally meaning “leftism” in the translation of Lenin’s work “The Infantile Disease of Leftism in Communism.” It is almost impossible to determine all the political beliefs of the students who actively took part in the uprising. The anarchist movement, whose center was Nanterre, was especially strong. There were quite a few people among the May activists who mocked leftist and anarchist slogans as well as any others. Many left-wing teachers at the Sorbonne also sympathized with the students, including, for example, Michel Foucault.

After a few days of unrest, trade unions came out and declared a strike, which then became indefinite; The protesters (both students and workers) put forward specific political demands.

en.wikipedia.org

* * *

01. May 3, 1968. Paris, France.

A showcase on Boulevard San Michele, broken during student performances.

02. May 1968, Paris. France.

Boulevard San Michele. Cobblestones in the air.

03. May 6, 1968. Paris, France.

Boulevard Saint-Germain. Clashes between students and police.

04. Events of May-June 1968, Paris. Mouna Aguigui (1911-1999), French anarchistic, haranguing the crowd, in the presence of two C.R.S.

05. Demonstration of young masked people. Paris, May 1968.

06. Demonstrators in the Latin Quarter 6th May 1968.

07. A demonstrator seen during a march in Paris yesterday which looks like saying death to De Gaulle 25th May 1968.

08. Leader of the so called "Enraged" students, Daniel Cohn-Bendit addressing fellows at the Gare de l"Est meeting in Paris. 14th May 1968.

09. Retreating students tumble and fall before the baton-swinging security police on the Boulevard St Michel. 18th June 1968.

10. Battles between police and students in Paris riot 7th May 1968.

11. Overturned cars used as barricades by rioting students block Gay Lussac Street. Several hundred students and police received hospital treatment after several battles between police and students in Paris 11th May 1968.

12. Wrecked cars and cobblestones baracade a street in Paris. Several hundred students and police received hospital treatment after numerous battles between police and students in the city centre. 13th May 1968.

13. An injured student demonstrator is escorted by a friend on Boulevard Saint-Michel. Several hundred students and police received hospital treatment after numerous battles between police and students in Paris 7th May 1968.

14. 1968: Paris Riots. A police man fires a tear gas bomb into the midst of the students, while his comrades armed with shields and sticks prepare to charge.

15. 25th May 1968: Paris Riots. Police are ordered to get even tougher by French Prime Minister, Georges Pompidou in a desperate attempt to restore order in Paris. The students are rioting.

16. 15th June 1968: Paris victory for the CRS. Over the weekend the CRS police in Paris succeeded in clearing the remaining students from the corridors and cells of the Sorbonne. Here a stduent is making Molotov cocktails in the cellars of the Sorbonne.

17. 25th May 1968: Paris riots. Cars that were overturned and set fire to during the riots. Police had been ordered to get tough by Prime Minister, George Pompidou.

18. Paris Riots, 25th May 1968: Parisians scramble over piles of cobble stones torn up to build barricades with.

19. Paris: In custody of helmeted gendarmes, a young man and women are led to an awaiting police van on the St. Germain Des Pres Square, during the huge demonstration by students in the Latin Quarter here on Monday 8 May 1968.

20. Paris: A barricaded street in front of the Bourse (seen background) following vicious street fighting between riot police and students in Paris, may 24th many rioters attacked the building and set it on fires 27th May 1968.

21. Paris: Violence again erupted in the Latin Quarter of Paris last night when some 6,000 left-wing students clashed with squads of special riot police. Here an injured demonstrator lies in the gutter after being involved in a clash with the police. 24 May 1968.

22. Paris: A C.R.S. Riot Policeman, his face protected against tear gas, subdues a young demonstrator during the riots which swept through Paris late May 24th,. After President De Gaulle has appealed to the nation to back his plans for social and economic reforms. The riot, which spread from the Bastille to the Latin Quarter, involved between 15,000 and 30,000 demonstartors. 27 May 1968.

23. Paris: Rioting students hurl all kind of missiles toward a police during a mass demonstration by students in the all-latin Quarter here today. Answering a call of the National Union of French Students they gathered by their thousands in the are to support the eight students threatened by being sacked from the University after last Friday's troubles. 6 May 1968.

24. Paris, events of May-June 1968. Demonstration of May 30, 1968 by "The Republic defense committees", on the Champs-Elysees. Among them: M. Poniatowski, P. Poujade, R. Boulin, M. Schumann, M. Debre, A. Malraux, P. Lefranc.

25. Events of May-June, 1968. Disentangled of May 13, 1968, bridge Saint Michel, Paris. JAC-20884-07.

26. May-June, 1968. Barricade street of the Saints-Peres, in front of the Faculty of Medicine. Paris, June 12, 1968.

27. Events of May-June, 1968. Students" demonstration, sit-in in the Champs-Elysees. Paris, May 7, 1968.

28. Events of May-June, 1968. Newsstand on Champs-Elysees. Paris, May 20, 1968.

29. Events of May, 1968 in Paris. Burden transport. Military trucks to the Disabled persons. May 26, 1968.

30. Events of May-June, 1968, Paris. Fire of the stock exchange, in May 24, 1968.

31. Events of May - June 1968, Paris. Evacuation of the occupied theater of the Odeon.

32. Gaullist demonstration. Paris. June 1968.

33. Poster in front of the Art college. Cartoon of Roger Frey, Minister of the Interior. Paris, June 1968.

34. Poster "Be young and shut up." Paris, 1968.

35. Events of May-June 1968, Paris. Courtyard of the Sorbonne occupied by the students. With the wall: portrait of Mao Zedong.

36. The events of May 1968. Demonstration Saint-Germain boulevard. Paris, the May 6, 1968.

37. Demonstrators throwing stones Boulevard Saint Michel May - June 1968.

38. Paris, evenements de mai-juin 1968. Manifestation du 6 May 1968 au Quartier Latin. Bagarre, boulevard Saint-Germain. Demonstration of the 6th May 1968 in the Latin Quarter, Boulevard St German.

39. Evenements de mai 1968 a Paris. Manifestants lancant des paves, boulevard Saint-Michel. Demonstrators throwing stones - Paris riots May 1968.

40. Paris, evenements de mai-juin 1968. Manifestation du 6 May 1968 au Quartier Latin. Bagarre, boulevard Saint-Germain. Paris riots of May - June 1968. Demonstration 6th May 1968 in the Latin Quarter.

* * *

Famous photographs of the Turkish photographer Goksina Sipahioglu.

41. De Gaulle makes his statement on television.

42.

43. A pacifist student puts a flower in the cap of a policeman defending the Sorbonne during the student riots. 06/16/68.

44. Two schoolchildren climb over the barricades. Paris. 06/11/68.

45. Student riots May 6, 1968.

46.

47.

* * *

Additional more detailed information about these events can be found here:

May 1968 events, or simply May 1968 fr. le Mai 1968 - a social crisis in France, resulting in demonstrations, riots and a general strike. Led ultimately to a change of government, the resignation of President Charles de Gaulle, and, in a broader sense, to huge changes in French society.

De Gaulle presented the United States with $750 million in exchange for gold. And the United States was forced to make this exchange at a fixed rate, since all the necessary formalities were observed.

Of course, such a scale of “intervention” could not “bring down the dollar”, but the blow was struck at the most vulnerable place - the “Achilles heel” of the dollar. General de Gaulle created a most dangerous precedent for the United States. Suffice it to say that from 1965 to 1967 alone, the United States was forced to exchange its dollars for 3,000 tons of pure gold. Following France, Germany presented dollars for exchange for gold.

In May 1968, a most interesting and still poorly understood event took place - in Paris. This is an extremely important phenomenon, still poorly analyzed and explained. Specialists in the field of social psychology and cultural studies seem to be afraid to start studying it. Let us remember the slogans of that time in France. "Red May" "Cultural Revolution". The “Golden Wheel of History” turns another page. “The people must replace the oligarchy.” In those days, French youth were already preparing to hang “bureaucrats on the guts of the bourgeoisie.” And this meant not only French bureaucrats. The French youth also sent a letter of their intentions to the USSR. For some reason, Soviet/Russian historical science did not focus attention on those already distant historical events that occurred in 1968 in France. For some reason, they did not consider it necessary to convey the French events to the Soviet people. For example, until 2005 I still did not know what exactly happened in France then. Today I would like to dwell once again on these events and look at them with different eyes, through the eyes of a person who saw a series of orange revolutions. I will try to present an alternative explanation for those events.

Let me remind you very briefly what happened in May 1968 in France. On March 22, in Nanterre, several student groups seized the administrative building, demanding the release of 6 of their comrades, members of the National Committee for the Defense of Vietnam, who, protesting against the Vietnam War, attacked the Paris office of American Express on March 20 and were arrested for this. On the same day, the anarchist “22 March Movement” was formed, which quickly radicalized the situation in Nanterre and involved a huge mass of students in revolutionary activities.

On March 29, students seized one of the halls at the Sorbonne University in Paris and held a rally there with the participation of members of the March 22 Movement, as well as representatives of rioting students from Italy, Germany, Belgium, West Berlin and Spain. At the same time, the “University Action Movement” (MAU) was created. Later, the IAU played a crucial role in “Red May” by creating “parallel courses”, in which, in defiance of official professors with their official “science,” courses of lectures were given by outstanding specialists invited by students from the non-university (and even non-academic) environment, and sometimes by themselves students who knew the subject well.

Police agents were sent to Nanterre, but the students managed (oh, professionals!!!) to photograph them and organized an exhibition of photographs at the university. The police tried to close the exhibition, clashes began, during which students forced the police out of the university.

On April 30, the administration charged eight student riot leaders with “inciting violence” and suspended classes at the university.

In response, on May 1, one hundred thousand people took to the streets of Paris. The youth chanted: “Youth work!” Demands for a 40-hour work week, trade union rights, and the repeal of the latest regulation to sharply cut the social security program were proclaimed. After this, the demonstrations did not stop.

On May 2, it was announced that classes would be suspended “for an indefinite period.” This was the spark that started the Red May fire. The National Students' Union of France (UNEF), together with the National Trade Union of Higher Education Workers, called on students to go on strike. Clashes with the police began, and rallies and demonstrations took place in protest in almost all university cities in France.

On May 3, Sorbonne students demonstrated in support of their Nanterre comrades. It was organized by the IJU. On the same day, printing workers threatened to strike, Parisian bus drivers went on strike against increasing the working day. The rector of the Sorbonne announced the cancellation of classes and called the police, who attacked the students using batons and tear gas grenades. The students took up the cobblestones. The clashes spread to almost the entire Latin Quarter of Paris. 2 thousand police officers and 2 thousand students took part in them, several hundred people were injured, 596 students were arrested.

On May 5, 13 students were convicted by a Paris court. In response, students created a “committee for defense against repression.” Junior teachers, many of whom sympathized with the students, called for a general strike at the universities. Small spontaneous demonstrations in the Latin Quarter were dispersed by the police. The IBA encouraged students to create “action committees”—grassroots (group and course level) structures of self-government and resistance. UNEF called on students and lyceum students throughout the country to go on an indefinite strike.

On May 6, 20 thousand people went out to protest, demanding the release of convicts, the opening of a university, the resignation of the Minister of Education and the rector of the Sorbonne, and an end to police violence. The students walked through Paris unhindered, and the population greeted them with applause. At the head of the column they carried a banner “We are a small bunch of extremists” (as the authorities called the participants in the student unrest the day before). When the column returned to the Latin Quarter, it was suddenly attacked by 6,000 police. The ranks of the demonstrators included not only students, but also teachers, lyceum students, and schoolchildren. The Latin Quarter began to be covered with barricades and soon the entire left bank of the Seine turned into an arena of violent clashes. Young people came from all over Paris to help the students, and by night the number of street fighters reached 30 thousand. It was not until 2 a.m. that the police dispersed the students. 600 people (on both sides) were injured, 421 were arrested. As a sign of solidarity, strikes and demonstrations broke out across the country by students, workers and employees in a wide range of industries and professions.

On May 7, all higher educational institutions and most lyceums in Paris went on strike. In Paris, 50 thousand students demonstrated, demanding the release of their comrades, the withdrawal of police from the territory of the Sorbonne and the democratization of higher education. In response, the authorities announced the expulsion from the Sorbonne of all participants in the riots. Late in the evening, near the Latin Quarter, the student column was again attacked by police forces.

The evening of May 7 was the beginning of a turning point in public opinion. The students were supported by almost all trade unions of teachers, teachers and researchers, and even the deeply bourgeois French League of Human Rights. The television workers' union issued a statement of protest due to the complete lack of objectivity in the media's coverage of student unrest. The next day, police unions (!) discussed demands and proposed holding an action on June 1st. Air traffic controllers threatened to go on strike. Horteni metallurgists who have been on strike for a month blocked one of the national highways for an hour.

On May 8, President de Gaulle declared: “I will not give in to violence,” and in response, a group of prominent French journalists created the “Committee against Repression.” The largest representatives of the French intelligentsia - Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Nathalie Sarraute, Francoise Sagan, Andre Gortz, Francois Mauriac and others - came out in support of the students. The French Nobel Prize winners made a similar statement. The students were supported by the largest trade union centers in France, and then by the parties of communists, socialists and left radicals. On this day, large demonstrations again took place in a number of cities, and in Paris so many people took to the streets that the police were forced to stand aside. The slogan appeared: “Students, workers and teachers - unite!” Red flags were visible everywhere and the chants of the International could be heard.

On May 10, a demonstration of 20,000 students trying to march to the Right Bank of the Seine to the buildings of the Television Authority and the Ministry of Justice was stopped on the bridges by the police. The demonstrators turned back, but on the Boulevard Saint-Michel they again encountered the forces of order. The students built 60 barricades, some of them up to 2 meters high. Boulevard Saint-Michel (and it is not small!) completely lost its paving stones, which students used as weapons against the police. Until 6 a.m., students surrounded in the Latin Quarter managed to resist the police. Result: 367 people were injured (including 32 seriously), 460 were arrested. The dispersal of the demonstration led to a general political crisis.

On the night of May 10–11, 1968, no one slept in Paris—it was simply impossible to fall asleep. Ambulances, firefighters, and police rushed through the streets, ringing the night with sirens. Tear gas grenades were heard exploding from the Latin Quarter. Entire families of Parisians sat at the radios: correspondents broadcast reports from the scene directly on the air. By 3 o’clock in the morning, a glow began to rise over the Latin Quarter: students retreating under the onslaught of special riot control units (analogous to the Russian riot police) set fire to the cars from which barricades were built…. The whole city knew that student unrest had been taking place at the Sorbonne since the beginning of May, but few expected that the matter would take such a serious turn. On the morning of May 11, newspapers came out with huge headlines: “Night of the Barricades.”

On May 11, opposition parties demanded an urgent convocation of the National Assembly, and Prime Minister Georges Pompidou spoke on television and radio and promised that the Sorbonne would open on May 13, the lockout would be lifted, and the cases of convicted students would be reviewed. But it was too late, the political crisis was gaining momentum.

On May 13, unions called on workers to support the students, and France was paralyzed by a 24-hour general strike, which involved almost the entire working population - 10 million people. A huge demonstration of 800,000 people took place in Paris, in the front row of which were the leader of the General Confederation of Labor (CGT), the communist Georges Séguy, and the anarchist Cohn-Bendit.

Immediately after the demonstration, the students seized the Sorbonne. They created “General Assemblies” - simultaneously debating clubs, legislative and executive bodies. The General Assembly of the Sorbonne declared the University of Paris "an autonomous people's university, open constantly and around the clock to all workers." At the same time, students captured the University of Strasbourg. In large provincial cities, demonstrations of solidarity of many thousands took place (for example, in Marseille - 50 thousand, Toulouse - 40 thousand, Bordeaux - 50 thousand, Lyon - 60 thousand.

On May 14, workers of the Sud-Aviation company in Nantes went on strike and, following the example of the students, seized the enterprise. From that moment on, occupations of factories by workers began to spread throughout France. The strike wave swept through the metallurgical and engineering industries and then spread to other industries. Above the gates of many plants and factories there were inscriptions “Occupied by Personnel”, and red flags above the roofs.

On May 15, students seized the Odeon theater in Paris and turned it into an open discussion club, raising two flags over it: red and black. The main slogan was: “Factories for workers, universities for students!” A group of writers seized the headquarters of the Society of Writers. The general meeting of the newborn writers' union put on the agenda the question of "the status of the writer in a socialist society." Filmmakers developed a program for updating the film industry in line with the planned socialist economy. Artists filled their works with social meaning and exhibited them in huge galleries - workshops of automobile and aircraft factories. On this day, strikes and occupations by factory workers covered Renault car factories, shipyards, and hospitals. Red flags hung everywhere. The strictest discipline was observed.