St. Bartholomew's Night. Night of Bloody Swords 1572 in France Catholics were killed

Florentine merchant's wife

Catherine de Medici is perhaps one of the most significant figures in the political arena of Europe in the 16th century. She was born in Florence and at the age of 14 she married the French Prince Henry de Valois. He, however, frankly speaking, did not love his Italian wife and tried in every possible way to limit her access to government affairs. And at the age of 19, Henry II threw half his kingdom at the feet of his mistress Diana de Poitiers, who was twice his age. In addition, Catherine, who was brought up in merchant Florence, had a hard time in the world: ignorance of etiquette and the French language aroused contempt among the courtiers.

Catherine de' Medici

From humiliation to limitless power

To strengthen herself, Catherine simply needed to give birth to an heir to the king. For a long time they thought that the queen was infertile, but magicians and alchemists led by Nostradamus did not give up: they began to treat the Medici with mule urine and tie cow dung to her belly. It is difficult to say which of these remedies had an effect, but the queen managed to give birth to Henry II’s son Francis.

The marriage of Catherine de Medici and Henry II was extremely unsuccessful

In 1559, the king died after a knightly tournament, and Catherine until the end of her days wore only black clothes as a sign of mourning. It is interesting that before this, white clothes were considered mourning in France, and it was the Medici who introduced the fashion for white. A year later, the heir Francis II died suddenly, after which the queen remained regent for her young son Charles IX. This made her one of the most powerful women in Europe.

King Charles IX of France

Woman on the throne

To strengthen Valois's position on the throne, Catherine arranged dynastic marriages. For example, she married the newly-crowned King Charles to the daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor, Elizabeth. The next step was to be the marriage of her daughter Margaret and Henry of Navarre. Henry's mother, Queen Joan, agreed, but on one condition: Henry would continue to adhere to the Huguenot faith, while the Medici herself was a Catholic. This agreement subsequently played a cruel joke on the Protestants.

Kill them all!

On August 18, 1572, Henry of Navarre arrived in Paris with a huge retinue, consisting of the most eminent Huguenots. We can say that for some time Catherine was tolerant of the Huguenots and even made concessions to them, but then she abruptly changed the direction of her policy. And this time the Medici decided to get rid of the Protestant elite. The assassination attempt on Gaspard de Coligny, the leader of the Huguenots, failed.

The queen's blacklist included about a dozen Protestant military leaders, and she also wanted to capture the formal leaders of the Huguenot party, the princes of the House of Bourbon, Henry of Navarre and the Prince de Condé. Many historians believe that the order “Then kill, kill them all!”, which King Charles IX gave on August 23, was not at all a call to begin the widespread killing of Huguenots. It is quite possible that he had in mind the very people on his mother’s list. But the situation got out of control.

Karl Goon "St. Bartholomew's Eve"

Good Catholics on the Warpath

The alarm, which the “good Catholics” of Paris regarded as a call to start a bloody massacre, sounded from the bell tower of the Church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois. Historians believe that in fact it could have just been a signal to kill the top of the Huguenots. But the angry commoners began to catch the Huguenots, who were easily recognizable by their black clothing, and tear them to pieces.

The Parisians did not spare the elderly, women or children. Some quietly decided to deal with creditors, rob neighbors, or even get rid of their annoying wife, so many ordinary Catholics died under the blows of swords. The dead were stripped of their clothes. The bloody massacre, which began on the eve of St. Bartholomew's Day, according to the most conservative estimates, claimed the lives of about 3,000 Huguenots, many of whom were very eminent. Only the princes of the blood were pardoned, Henry of Navarre and the Prince de Condé, who, however, were forced to accept the Catholic faith.

Francois Debois, image of St. Bartholomew's Night

The wave of violence that swept through Paris spilled beyond the capital and engulfed the entire country. Some historians suggest calling this massacre not the Night of St. Bartholomew, but the Season of St. Bartholomew. The number of victims is usually estimated from 8,000 to 30,000 thousand. The events of August 1572 became a turning point in the French Wars of Religion, which lasted more than 30 years. In the memory of Protestants, Catholics were entrenched as cruel people, and Catherine de Medici gained fame as an evil Italian queen.

Catherine de Medici was called the black queen

Goody Huguenots

The portrayal of the Huguenots as innocent victims in this case is not entirely accurate. The fact is that the Protestants also had their finger on the gun. For example, in 1567 in Nîmes, French Protestants carried out a massacre of Catholic priests and monks. During the fair, they gathered the most important Catholics, killed them and threw them into a well. Of course, the scale of Michelada in Nimes is not comparable to St. Bartholomew's Night - as a result, about 90 people died. But the fact remains: the Huguenots took an active position in the Wars of Religion, and they cannot be called poor sheep.

Edouard Debat-Ponsant "Morning at the gates of the Louvre." Catherine de' Medici looks at the bodies of the dead

Europe received the news of the bloody massacre in France extremely negatively. Henry of Anjou, who was directly involved in planning St. Bartholomew's Night, was nicknamed the “meat king.” Queen Elizabeth of England was also outraged by the behavior of the French. And Ivan the Terrible wrote a letter to Emperor Maximilian II, in which he expressed his extreme dissatisfaction with such reprehensible treatment of people.

It should be noted that hatred, and the cruelty it generated, was mutual at that time. Enmity was caused not only by religious reasons, but also by socio-political ones. St. Bartholomew's Night was not an isolated act of violence. It was the culmination of many years of confrontation (1560 - 1598) between French Catholics and Protestants, and it is in this context that it should be considered.

During the religious wars, Protestants in France represented a serious force, which the royal house of Valois, not unreasonably, considered a threat to its power. The Huguenots had their own well-armed army, controlled important fortified cities, and were supported and financed by representatives of noble families. Twice the Protestants unsuccessfully tried to kidnap the French monarchs in order to subjugate them to their influence.

Initially, the Huguenots were distrustful of harsh methods of struggle. But in the 1560s, after a wave of Catholic violence swept across the country, they launched their reign of terror. They robbed and destroyed temples and monasteries, destroyed icons and tortured monks who hid religious shrines. In a number of places, priests were hanged, many of them were mutilated, their noses, ears and genitals were cut off. The most widespread massacre was the “Michael Massacre” in Nîmes or “Michelada”. On the night of September 29-30, 1567, having gathered the most prominent local Catholics in the palace of the Bishop of Nîmes, the Protestants killed them and threw their bodies into a nearby well. In total, according to various estimates, from 80 to 90 people died. This execution made a strong impression on Catholics, becoming one of the reasons for the next round of religious conflict.

However, the violence on both sides was of a different nature. To better understand the essence of this enmity, it is worth quoting the book of the French historian Jean-Marie Constant “The Daily Life of the French during the Wars of Religion”:

“The violence committed by the Catholic mob is truly mystical rage, a “sacred” act, committed by the will of the Lord himself, who wished to exterminate the supporters of the new religion, equated with heretics and worshipers of Satan. The Catholics were so eager to punish the Protestants that without the slightest regret they maimed them, tormented them, threw them to dogs, threw them into water, burned them, inflicting on them the torment on earth that awaited them in the afterlife. Thus, while waiting for the Lord to descend to them and give his sign, they cleansed the Christian world from filth. Children played an important role in restoring the original purity: they personified the innocence of those who acted as judges.

The violence committed by the Calvinists was of a completely different nature. It was rationally justified, carefully calculated, programmed and carried out under the control of the new elite of the reformed church. It consisted in the systematic destruction of church symbols, images of saints, icons, statues, expensive things that were kept in churches, in the physical destruction of these things or in melting them down (to be used for other purposes) to return them to their original evangelical purity. Not content with destroying idols, Protestants persecuted clergy, “those with tonsures” (razes), since, in their opinion, it was they who prevented the people from turning their gaze to the true faith.”

Speaking about the reasons for hatred of the Huguenots, it is important to consider that Paris was a traditionally Catholic city, and the townspeople reacted with hostility to the large number of Huguenots who arrived in August 1572 for the wedding of Margaret of Valois and Henry of Navarre. In addition, the large Parisian poor were irritated by the wealth and luxury of the Protestant guests.

It is worth noting that during the Night of St. Bartholomew, its ordinary participants were not always motivated by religious reasons. Some simply settled personal scores with those whom they disliked for various reasons. In such cases, sometimes Catholics also fell under the hot hand.

There is also an opinion that, when planning the action in Paris, the Catholic Party did not at all strive for the massacre of Protestants. The goal of the Catholics was to destroy the main leaders of the Huguenots and capture Henry of Navarre, but due to the intense hostility of the Parisians towards the Protestants, events got out of control and everything resulted in a bloodbath.

The events of St. Bartholomew's Night became a turning point in the French Wars of Religion. Despite the fact that the conflict continued for many years after these events, the Protestants were dealt a powerful blow. They have lost their most prominent leaders. About 200 thousand Huguenots were forced to flee the country.

This is not the essence of excess. It is difficult (and even incorrect) to view St. Bartholomew's Night only as mutual religious hatred that resulted in a bloody incident.

The term "Bartholomew's Night" has long been used as a symbol of cruel and bloody massacre. But often those who use it know little about what is really behind it.

Christians against Rome

In the first half of the 16th century, a split began in Western Christianity. The Roman Church, which concentrated in its hands not only spiritual power, but also great influence in secular affairs, began to cause discontent among believers. The parishioners were irritated by the enormous wealth concentrated in the hands of the holy fathers and their, to put it mildly, not the most ascetic way of life. The Church was accused of moving away from the principles of true Christianity.

Thus began the Reformation, which gave birth to Protestantism - a collection of independent churches, church unions and denominations built on principles different from the Roman canons.

The Catholic Church, trying to defend its exceptional position, began a tough fight against Protestants. Europe entered an era of religious wars, which to one degree or another affected all the leading states of Western Europe.

Henry of Navarre and Margaret of Valois. Reproduction

Wedding for peace

In France, the confrontation between Catholics and Protestants - the Huguenots - resulted in a series of bloody wars that lasted almost forty years.

These wars destroyed and weakened the state, which lost the opportunity to defend its interests in the international arena.

On August 8, 1570, the Treaty of Germain was signed, ending the Third Huguenot War.

The wedding of the French woman was supposed to put an end to the enmity of the two religious camps Catholic princess Margaret of Valois And Protestant leader Henry of Navarre.

The entire elite of France, both Catholics and Protestants, came to Paris for the wedding of 19-year-old “Queen Margot” and 18-year-old Henry. On August 18, 1572, the marriage took place.

Representatives of the moderate forces rejoiced - the war had finally come to an end.

Catholic conspiracy

But Catholic radicals were furious. First of all, this concerned Henry I de Lorrain, 3rd Duke of Guise. The fact is that among those who arrived for the celebrations was one of the Huguenot leaders, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny. The admiral was a sworn enemy of the Guise family. Queen Mother Catherine de Medici, a master of conspiracies, called on the Duke of Guise to take revenge on the admiral for his deceased father, who fell in a battle with the Huguenots.

Historians disagree on who was more active in this conspiracy - the Duke or the Queen Mother. Be that as it may, on August 22, a hitman hired by the Duke of Guise shot at de Coligny, but only wounded him in the arm.

A fragment of a painting by Francois Dubois: Catherine de Medici looks at the bodies. Reproduction

The situation became more complicated - after the conclusion of peace, the admiral was included in the Royal Council, and became one of the closest advisers to King Charles IX. De Coligny appealed to the king to punish those who attempted to kill him.

Catholics gathered for an urgent council. Historians disagree about who exactly was the main ideologist of the next decision, but in the end they agreed that if it was not possible to kill one Huguenot, then they all had to be killed. Moreover, they so successfully gathered in Paris because of the royal wedding.

“Are you the admiral?”

As for the performers, there were more than enough of them - the masses of Paris consisted mainly of Catholics. To the hostility towards the Huguenots at this time was added irritation by the luxurious wedding, while the Parisians lived from hand to mouth.

Some believe that Catherine de Medici, the Duke of Guise and the king did not initially plan a large-scale massacre. It was planned to finish off de Coligny, a dozen and a half Huguenot military leaders, and capture Henry of Navarre and his cousin of the Prince de Condé, and stop there.

The Catholics involved in the conspiracy were urgently notified. A white bandage on the arm was chosen as a distinctive sign, so as not to confuse our own with strangers.

On the night of August 23-24, 1572, on the eve of St. Bartholomew's Day, Charles IX gave the order to the Catholics gathered in the palace to “cut off the head of the admiral and the people from his retinue.”

At three o'clock in the morning the alarm bell sounded in the bell tower of the Church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois. For Catholics this was the signal to attack.

Admiral de Coligny was one of the first to die. Burst into his bedroom Bohemian mercenary Karl Dianovitz, nicknamed Boehm. Finding de Coligny in his nightgown, he asked rudely: “Are you the admiral?” De Coligny replied: “Young man, respect my old age.” Bem pierced him with a sword, and when removing it, he tore his face in two. The dead man's body was thrown out the window.

Victims and Saviors

Initially, the killers actually acted according to plan, eliminating their main enemies. But very quickly the situation got out of control.

The Parisians, inflamed by religious hysteria, began to kill all the Huguenots, sparing neither the elderly, nor women, nor children. The murders were accompanied by robberies.

The longer the massacre lasted, the more indiscriminate the killers became. On the quiet, one could kill a Catholic neighbor with whom there was a long-standing conflict, or rob a house one liked, regardless of who lived there.

When the sun rose, a terrible sight met the eyes of the residents of Paris - the streets of the city were strewn with hundreds of tortured corpses. Even the initiators of the massacre were horrified by what they had done.

It cannot be said that all Catholics took part in the massacre. Margarita Valois, through her personal intercession, saved the lives of her husband and several other Huguenots who found refuge in her bedroom. Ordinary Catholics hid Huguenots in their homes - some unselfishly, and some for pay.

The killings began to decline, but did not stop, so that three days later Charles IX had to send troops to forcefully stop the atrocities. Reprisals against the Huguenots also occurred in several other cities in France, where news of the Parisian events reached.

Ivan the Terrible is terrified

The exact number of victims of St. Bartholomew's Night is unknown. It is believed to range from 5,000 to 30,000 people.

This was quite enough to declare St. Bartholomew's Night the largest religious massacre of the 16th century.

Even Russian Tsar Ivan the Terrible drew attention to her. In a letter Emperor Maximilian II he wrote: “And what, dearest brother, do you mourn the bloodshed that happened to the King of France in his kingdom, several thousand were beaten to the point of mere babies; and it is fitting for the peasant sovereign to mourn that the French king committed such inhumanity over so many people and shed so much blood without reason.”

Despite the death of the main leaders of the Huguenots, the French Protestants did not give up. The country was faced with a new series of religious wars, both bloody and senseless. And the final consolidation of the equality of Protestants in France occurred only in the 19th century.

Bartholomew's NIGHT

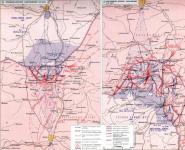

On August 24, 1572, events took place in Paris and throughout France that later received the name “Bartholomew’s Night.” On the night before St. Bartholomew's Day, Catholics, on the orders of Charles IX and his mother Catherine de Medici, carried out a massacre of Protestant Huguenots.

Francois Dubois "Bartholomew's Night". XVI century.

A picture of that time. In the 16th century, a painting depicting a historical event could easily combine different time layers. And here it is: in the foreground is what happened on the night of the massacre, and then what happened after. Note the figure of Catherine de Medici in a black dress in the distance on the left. When everything calmed down, she specifically came out of the Louvre to look at the murdered Protestants, this is a historical fact. Catherine is always depicted in black, and rightly so - after the death of her husband, she wore mourning for the rest of her life, taking it off only on rare solemn occasions. In general, everything is accurate here - according to eyewitnesses, the water of the Seine was indeed red with blood.

This massacre was made possible by a complex combination of political, religious and psychological factors, the constant struggle for primacy between France, Spain and England, as well as violent contradictions within France itself. In the first place in the complex tangle of motives that led to the tragedy was the concept of the Reformation. When, on the last day of October 1517, Luther nailed his 95 theses to the door of the church, and a little later Calvin in Geneva developed his doctrine of absolute predestination, the prerequisites for the Night of St. Bartholomew were already created; all that remained was to wait until there was enough gunpowder in the European barrel and there would be the right person with fire.

Nowadays, it is very difficult to understand why some Christians called others heretics and were ready to kill or send to the stake those who do not attend mass, do not recognize the authority of the Pope, or, on the contrary, diligently go to church, venerate the Mother of God and the saints. For a man of the Middle Ages, religion remained one of the most important factors in his life. Of course, rulers could easily switch from Catholicism to Protestantism and back, depending on the political situation, noble people could buy indulgences without much concern for their moral state, and ordinary people could respond to religious wars, while pursuing completely earthly goals.

In this struggle between Protestants and Catholics, it would be wrong to consider one of the sides as progressive and humane, and the other as cruel and archaic. Regardless of their affiliation with a particular Christian denomination, politicians in France and beyond could demonstrate both an example of nobility and miracles of cunning and cunning - bloody pogroms occurred periodically, the victims of which were first one side or the other. Here, for example, is what was said in a Protestant leaflet distributed in Paris on October 18, 1534: “I call heaven and earth as witnesses of the truth against this pompous and proud papal mass, which crushes and one day will completely crush the world, plunge it into the abyss, destroy and devastate.” Catholics did not lag behind the Protestants, sending their opponents to the stake as heretics. However, the burned martyrs gave birth to more and more new followers, so Catherine de Medici, who ruled France in the second half of the 16th century, had to show miracles of resourcefulness in order to maintain at least the appearance of the unity of the country.

The world around was rapidly changing - more and more people considered religion to be their private matter, fewer and fewer Christians needed the mediation of the Church. This individualization of faith did not bring peace to people - sermons dedicated to the torments of hell, the Last Judgment and the Dance of Death became louder and louder, and the voice of Christian mercy and love sounded ever quieter. Under these conditions, the main weapon of Protestants and Catholics became intrigue, and not the ability to convey their beliefs to others. Power over France was the driving force behind these battles, in which religion played a very important role. On August 24, 1572, Catholics killed the Huguenots with the full knowledge that this fury of the crowd was pleasing to God: “You can see what the power of religious passion can become, and it seems incomprehensible and barbaric when you see on all the local streets people cold-bloodedly committing cruelties against harmless compatriots, often acquaintances and relatives.”. The author of these words, the Venetian envoy Giovanni Michieli, was one of the eyewitnesses of what was happening.

St. Bartholomew's Night was immediately preceded by two events - the wedding of the king's favorite, his sister, the Catholic Margaret de Valois, with the Huguenot leader Henry of Navarre. It was a desperate attempt by Catherine de Medici to maintain peace in France, but it ended in failure. The Pope did not give permission for the marriage, Henry was accompanied by a large retinue of wealthy Huguenots, all events took place in the Catholic quarter of Paris, and Protestants were promised to be forced to visit the Catholic Cathedral. The townspeople were outraged by the ostentatious luxury of the ceremony - all this led to tragedy a few days later.

The formal reason for the start of the massacre was the unsuccessful attempt on the life of another Huguenot leader, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny. He encouraged King Charles IX to go to war with Catholic Spain in alliance with England. A personally brave man, with a permanent toothpick in his mouth, which he chewed during times of stress, the admiral survived several attempts on his life. The latter took place on the eve of the tragedy: a shot from an arquebus was heard at the moment when Coligny bent down. Two bullets tore off one of his fingers and lodged in his other hand, but this assassination attempt, ordered by Catherine de Medici, who did not want war with Spain, made the massacre almost inevitable, since there were many Huguenots in Paris, and the city itself was mainly inhabited by Catholics.

It all started with a signal from the bell tower of the Church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerre. Having exterminated the leaders of the Protestants, the crowd rushed to kill indiscriminately everyone who was not Catholic. Bloody scenes played out on the streets of Paris and other cities, old people, women and children were killed. Already On the morning of August 24, enterprising businessmen began selling homemade talismans with the inscription “Jesus-Mary”, which were supposed to protect against pogrom.

Frightened by the atrocities, Charles IX already on August 25 takes the Protestants under his protection: “His Majesty wishes to know exactly the names and nicknames of all those who adhere to the Protestant faith, who have houses in this city and its suburbs... (King - A.Z.) desires that the said quarterly elders command the masters and mistresses or those who live in the said houses to carefully guard all who adhere to the said faith, so that no harm or displeasure is caused to them, but good and reliable protection is provided.” The royal order could not stop the flow of murders - until mid-September, and in some areas even longer, Huguenots were robbed and killed throughout France. Historians have different estimates of the number of victims of St. Bartholomew's Night. The maximalists spoke of 100,000 dead; the real figure was much lower - about 40,000 throughout France.

On August 28, 1572, a leaflet appears in Paris demonstrating the cruelty to which the participants in the massacre descended in four days: “From now on, no one dared to capture and hold a prisoner for the reason stated above, without the special order of the king or his servants, and not to try to take horses, mares, bulls, cows and other livestock from the fields, estates or estates ... and not to insult not by word or action of workers, but to allow them to produce and carry out their work in peace with all safety and to follow their calling.” But this statement of Charles IX could not stop the massacre. The desire to take possession of the property and lives of people who were actually outlawed was too tempting for many. The religious component of what was happening finally faded into the background, and the cruelty of individual scoundrels who killed hundreds of Huguenots came to the fore (one killed 400 people, the other - 120, and this is only in Paris). Fortunately, most people retained their human appearance and even hid the children of Protestants, saving them from villains.

The most interesting reaction to St. Bartholomew's Night was the statement of ardent adherents of Catholicism. The Duke of Nevers, in a long memorandum, justified Charles IX, believing that the king was not responsible for the massacres committed by “the vile urban rabble, unarmed except for small knives.” The Duke called the participants in the pogroms themselves servants of God who helped “cleanse and ennoble His Church.” History has shown that an attempt to save a country or faith by killing part of the population is doomed to failure. The struggle between Protestants and Catholics continued for several centuries.

Andrey ZAYTSEV

Bartholomew's Night or "massacre in honor of St. Bartholomew" (Massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy) began in Paris on the night of August 24, 1572, on the eve of the feast of St. Bartholomew, and lasted three days. The killers did not even spare babies.

“Neither gender nor age evoked compassion. It really was a massacre. The streets were littered with corpses, naked and tortured, and the corpses floated along the river. The killers left the left sleeve of their shirt open. Their password was: “Praise the Lord and the King!”- a witness of the events recalled.

The massacre of Protestant Huguenots on St. Bartholomew's Night was organized by the will of Queen Catherine de Medici; her weak-willed son, King Charles IX, did not dare to disobey his imperious mother.

The sad angel of the Church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois in Paris, from which at three o'clock in the morning the bell rang - a signal for the beginning of the massacre of the Huguenots.

Both Catholics and Huguenots died in the battles of St. Bartholomew's Night. City bandits took advantage of the general turmoil, robbing and killing Parisians with impunity, regardless of their religious views. It was up to the city guard to restore order in Paris, who “as always were the last to come running.”

On the eve of the bloody night, the leader of the Huguenots, Admiral de Coligny, was predicted that he would be hanged. The powerful leader of the Huguenots, whom half of France actually worshiped, laughed at the magician.

“It is said that Coligny received eight days ago, together with his son-in-law Teligny, the prediction of an astrologer, who said that he would be hanged, for which he was ridiculed, but the admiral said: “Look, there is a sign that the prediction is true; at least, I heard the day before that my effigy, such as I was, would be hanged within a few months.” So the astrologer spoke the truth, for his corpse, dragged through the streets and mocked to the end, was beheaded and hanged by the feet on the gallows of Montfaucon to become prey for crows.

Such a pitiful end befell the one who had recently been the ruler of half of France. They found a medal on it, on which were engraved the words: “Either complete victory, or lasting peace, or an honorable death.” “Not one of these wishes was destined to come true,” wrote the court doctor, who witnessed the bloody events.

It is believed that initially the queen wanted to get rid of only the leader of the Huguenots, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny and his associates, but the planned political murder spontaneously escalated into a massacre.

According to another version, the massacres were also planned. The Queen decided to put an end to Huguenot claims in France forever. St. Bartholomew's Night began 10 days after the wedding of Catherine's daughter Margot with Henry of Navarre, a Huguenot by religion. All the Huguenot nobility came to the celebration; no one imagined that they would soon face cruel reprisals.

On the eve of St. Bartholomew's Day. A young Catholic lady tries to tie a white bandage on her Huguenot lover, the identifying mark of Catholics. He hugs the lady and removes the blindfold.

On the eve of St. Bartholomew's Night, August 22, there was an assassination attempt on Admiral Coligny. Catherine de Medici and Charles came to him on a courtesy visit. Coligny warned them that if the assassination attempt was repeated, he would strike back at the royal family.

According to letters from the Spanish ambassador:

“On the said day, August 22, the most Christian king and his mother visited the admiral, who told the king that even if he lost his left arm, he would have his right arm to take revenge, as well as 200 thousand people ready to come to his aid to repay for the insult: to which the king replied that he himself, although a monarch, had never been able and would never be able to raise more than 50 thousand people.”

The Ambassador describes the course of events of St. Bartholomew's Night. At midnight on August 23, the king called his entourage and ordered Coligny to be killed, he ordered " cut off the head of the admiral and the people from his retinue.”

The Church of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois with the tower, from where, according to legend, the signal for the beginning of St. Bartholomew’s Night was given (without repairs in the frame there is no way)

At three o'clock in the morning on August 24, the signal to begin the “operation” sounded:

“On Sunday, St. Bartholomew’s Day, the alarm sounded at 3 o’clock in the morning; all the Parisians began to kill the Huguenots in the city, breaking down the doors of houses inhabited by them and plundering everything they found.

Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois was built in the 12th century on the site of an ancient temple, the favorite temple of Catherine de' Medici. Over the centuries the church has been rebuilt

“King Charles, who was very careful and always obeyed the Queen Mother, being a zealous Catholic, understood what was going on and immediately decided to join the Queen Mother, not to contradict her will and resort to the help of Catholics, fleeing the Huguenots...”- Queen Margot writes about the influence of her mother, Catherine de Medici, on her weak-willed brother, Charles.

King Charles IX

The main goal of St. Bartholomew's Night was the elimination of Coligny and his entourage. The king personally gave orders to his people.

According to the recollections of the royal physician:

“They held a council all night in the Louvre. The guards were doubled and, so as not to alert the admiral, no one was allowed to go out except those who presented the king’s special pass.

All the ladies gathered in the queen's bedchamber and, unaware of what was being prepared, were half dead with fear. Finally, when they began the execution, the queen informed them that the traitors had decided to kill her on the coming Tuesday, her, the king and the entire court, if you believe the letters she received. The ladies were speechless at this news. The king did not undress at night; but, laughing with all his might, he listened to the opinions of those who composed the council, that is, Giza, Nevers, Montpensier, Tavanna, Retz, Biraga and Morvilliers. When Morvillier, who had been awakened and appeared, all alarmed as to why the king had sent for him at such an hour, heard from the lips of His Majesty the subject of this night's conference, he felt such a fear seize his heart that before the king himself came to him turned, he slumped in his place, unable to utter a word.

When he felt somewhat better, His Majesty asked him to express his opinion. “Sire,” he replied, “this matter is quite serious and important, and it can again initiate a civil war, more ruthless than ever.” Then, as the king questioned him, he pointed out to him the imminent danger and ended, after much hesitation and subterfuge, with the conclusion that if all that he had been told was true, the will of the king and queen must be carried out and the Huguenots put to death. And while he spoke, he could not hold back his sighs and tears.

The king sent without delay for the king of Navarre and the prince de Condé, and at this inopportune hour they appeared in the king's bedchamber, accompanied by people from their retinue.

When the latter, among whom were Monen and Pil, wanted to enter, guard soldiers blocked their way. Then the King of Navarre, turning to his people with a dejected face, said to them: “Farewell, my friends. God knows if I will see you again!

The church tower from which the signal was given for the start of the massacres

At the same moment, Guise left the palace and went to the captain of the city militia to give him the order to arm two thousand people and surround the Faubourg Saint-Germain, where more than fifteen hundred Huguenots lived, so that the massacre would begin simultaneously on both banks of the river.

Nevers, Montpensier and the other lords immediately armed themselves and, together with their men, partly on foot and partly on horseback, took up the various positions which had been assigned to them, ready to act together.

The king and his brothers did not leave the Louvre.

Caussin, the captain of the Gascons, the German Boehm, the former page of M. de Guise, Hautefort, the Italians Pierre Paul Tossigny and Petrucci with a large detachment came to the hotel of the admiral, whom they were ordered to kill. They broke down the door and climbed the stairs. At the top they came across a sort of makeshift barricade formed from hastily piled chests and benches. They entered and encountered eight or nine servants, whom they killed, and saw the admiral standing at the foot of his bed, dressed in a fur-lined dress.

Dawn began to break, and everything around was dimly visible. They asked him: “Are you the admiral?” He replied yes. Then they pounced on him and showered him with blows. Bem pulled out his sword and prepared to thrust it into his chest. But he: “Ah, young soldier,” he said, “have mercy on my old age!” Vain words! With one blow Bem knocked him down; Two pistols were discharged into his face and he was left prostrate and lifeless. The entire hotel was looted.

Meanwhile, some of these people came out onto the balcony and said: “He’s dead!” Those below, Guise and others, did not want to believe. They demanded that he be thrown out of their window, which was done. The corpse was robbed and, when it was naked, torn to shreds...”

The ambitious admiral Gaspard de Coligny died on St. Bartholomew's Night

The Spanish ambassador describes Coligny's murder a little differently:

“The aforementioned Guise, d'Aumal and d'Angoulême attacked the admiral's house and entered it, putting to death eight of the Prince of Béarn's Swiss, who were guarding the house and trying to defend it. They went up to the master's chambers and, while he was lying on the bed, the Duke of Guise fired a pistol at his head; then they grabbed him and threw him naked out of the window into the courtyard of his hotel, where he received many more blows with swords and daggers. When they wanted to throw him out of the window, he said: “Oh, sir, have mercy on my old age!” But he wasn't given time to say more

...Other Catholic nobles and courtiers killed many Huguenot nobles...

...On the said Sunday and the following Monday, he saw the corpses of the admiral, La Rochefoucauld, Teligny, Briquemo, the Marquis de Rieux, Saint-Georges, Beauvoir, Peel and others being dragged through the streets; they were then thrown onto a cart, and it is not known whether the admiral was hanged, but the others were thrown into the river.”

Meanwhile, massacres continued in Paris; good Catholics did not spare those of other faiths.

“...Cries were heard: “Beat them, beat them!” There was a fair amount of noise, and the carnage kept growing...

... Nevers and Montpensier combed the city with detachments of infantry and horsemen, making sure that they attacked only the Huguenots. No one was spared. Their houses, numbering about four hundred, were robbed, not counting their rented rooms and hotels. Fifteen hundred persons were killed on one day and the same number on the next two days. All that could be found were people who fled and others who pursued them, shouting: “Beat them, beat them!” There were men and women who, when, with a knife put to their throat, they were demanded to renounce in order to save their lives, they persisted, thus losing their soul along with their life...

As soon as daylight came, the Duke of Anjou mounted his horse and rode through the city and its suburbs with eight hundred horse, a thousand foot, and four picked troops destined to storm the houses that offered resistance. No assault was required. Taken by surprise, the Huguenots thought only of escape.

Among the screams there was no laughter. The winners did not allow themselves, as usual, to vigorously express joy, the sight that appeared before their eyes was so heartbreaking and terrible...

The Louvre remained locked, everything was immersed in horror and silence. The king did not leave his bedchamber; he looked pleased, had fun and laughed. The yard had long been put in order, and calm had almost been restored. Today everyone is eager to take advantage of opportunities, seeking positions or favors. Until now, no one would have allowed the Marquis de Villars to take the position of admiral. The king is frightened, and it is unclear what he will command now..."

Next to the church tower and arch is the district mayor's office

Many foreigners of other religious denominations became victims of murderers. Guests of the French capital had to pay a lot of money for shelter in the homes of Parisians. Often the owners threatened to hand them over to the murderers as Huguenots if they did not pay.

An Austrian student described his view of the bloody events. Neither women nor children were spared. Compassionate townspeople who tried to save Huguenot children were also killed as traitors:

“Haitzkofler and many of his fellow students lived and ate with the priest Blandy, in a very good house. Blandy advised them not to look out of their windows for fear of the gangs that were roaming the streets. He himself positioned himself in front of the front door in priestly vestments and a four-cornered hat; Moreover, he enjoyed the respect of his neighbors. Not an hour passed without a new crowd appearing and asking if there were any Huguenot birds lurking in the house. Blandy replied that he did not give shelter to any birds except students, but only from Austria and Bavaria; Besides, doesn’t everyone around him know him? Is he capable of sheltering a bad Catholic under his roof? And so he sent everyone away. And in return, he took a good amount of crowns from his boarders, by right of redemption, constantly threatening that he would no longer protect anyone if the outrages did not end.

I had to scrape down the bottom, where there wasn’t much left, and pay for board three months in advance. Three of their dining companions, French Picardians, refused to pay (perhaps they did not have the required amount). So, they did not dare to stick their heads out, because they would have endangered their lives, and begged Gaitzkofler and his friends to supply them with traveling clothing, which they brought from Germany: with such a change of clothes, a change of housing would not pose such a danger. And so these good Picardians left the priest's house; their old comrades never knew where they had gone, but one poor man came to tell Gaitzkofler that they were in a fairly safe place, that they thanked them from the bottom of their hearts and would like to express their gratitude in person as soon as possible; finally, they ask permission to keep for the time being the clothes that were given to them.

The killings began to decline after the royal proclamation, although they did not stop completely. People were arrested at home and taken away; This was seen by Gaitzkofler and his comrades from a window in the roof of the house. The house stood at the crossroads of three streets, inhabited mainly by booksellers, who had burned books worth many thousands of crowns. The wife of one bookbinder, to whom her two children clung, prayed at home in French; a detachment appeared and wanted to arrest her; since she refused to leave her children, she was finally allowed to take their hands. Closer to the Seine they met other pogromists; they screamed that this woman was an arch-Huguenot, and soon they threw her into the water, followed by her children. Meanwhile, one man, moved by compassion, got into a boat and saved two young creatures, causing the extreme displeasure of one of his relatives and the closest heir, and was then killed, since he lived richly.

The Germans did not count more than 8-10 victims among their own, who, due to imprudence, ventured out into the suburbs too early. Two of them were about to cross the drawbridge at the front gate when a sentry accosted them and asked if they were good Catholics. “Yes, why not?” - one of them answered in confusion. The sentry replied: “Since you are a good Catholic (the second called himself a canon from Munster), read “Salve, Regina.” The unfortunate man could not cope, and the sentry pushed him into the ditch with his halberd; This is how those days ended in the Faubourg Saint-Germain. His companion was a native of the bishopric of Bamberg; he had a beautiful gold chain hanging around his neck, because he believed that looking important would help him leave. The guards nevertheless attacked him, he defended himself with two servants, and all three died. Having learned that their victim had left the beautiful horses at the German Iron Cross Hotel, not far from the university, the killers hastened there to pick them up.”

Other cities were also hit by a wave of mass religious murders.

“At Rouen 10 or 12 hundred Huguenots were killed; in Meaux and Orleans they got rid of them completely. And when M. de Gomicourt was preparing to return, he asked the Queen Mother the answer to his commission: she answered him that she did not know any other answer than the one that Jesus Christ gave to the disciples, according to the Gospel of John, and said in Latin: “Ite et nuntiate quo vidistis et audivistis; coeci vedent, claudi ambulant, leprosi mundantur,” etc., and told him not to forget to tell the Duke of Alba: “Beatus, qui non fuerit in me scandalisatus,” and that she would always maintain good mutual relations with the Catholic sovereign.”

Memoirs of Queen Margot about St. Bartholomew's Night:

Queen Margot, episode of the film with Isabelle Adjani

“It was decided to carry out the massacre on the same night - on St. Bartholomew. We immediately began to implement this plan. All the traps were set, the alarms rang, everyone ran to their quarters, in accordance with the order, to all the Huguenots and to the admiral. Monsieur de Guise sent the German nobleman Bem to the admiral's house, who, going up to his room, pierced him with a dagger and threw him through the window at the feet of his master, Monsieur de Guise.

They didn’t tell me anything about all this, but I saw everyone at work. The Huguenots were in despair at this act, and all the de Guises whispered, fearing that they would not want to take proper revenge on them. Both the Huguenots and the Catholics treated me with suspicion: the Huguenots because I was a Catholic, and the Catholics because I married the King of Navarre, who was a Huguenot.

They didn’t say anything to me until the evening, when in the Queen Mother’s bedroom, who was going to bed, I was sitting on a chest next to my sister, the Princess of Lorraine, who was very sad.

The Queen Mother, talking to someone, noticed me and told me to go to bed. I curtsied, and my sister took me by the hand, stopped me and burst into tears loudly, saying through her tears: “For God’s sake, sister, don’t go there.” These words scared me very much. The Queen Mother, noticing this, called her sister and angrily forbade her to tell me anything. My sister objected to her that she did not understand why she would sacrifice me by sending me there. There is no doubt that if the Huguenots suspect something is wrong, they will want to take out all their anger on me. The Queen Mother replied that God willing, nothing bad would happen to me, but be that as it may, I needed to go to bed, otherwise they might suspect something was wrong, which would prevent the plan from being carried out.

Margot saves a Huguenot on St. Bartholomew's Night

I saw that they were arguing, but I didn’t hear about what. The Queen Mother once again sternly ordered me to go to bed. Shedding tears, my sister wished me good night, not daring to say anything more, and I left, numb with fear, with a doomed look, not imagining what I should be afraid of. Once at home, I turned to God in prayer, asking him to protect me, not knowing from whom or from what. Seeing this, my husband, who was already in bed, told me to go to bed, which I did. Around his bed stood from 30 to 40 Huguenots, whom I did not yet know, since only a few days had passed since our wedding. All night they did nothing but discuss what had happened with the admiral, deciding at dawn to turn to the king and demand punishment for Monsieur de Guise. Otherwise, they threatened that they would deal with him themselves. I couldn’t sleep, remembering my sister’s tears, overwhelmed by the fear they aroused in me, not knowing what I should be afraid of. So the night passed, and I didn’t sleep a wink. At dawn my husband said he wanted to go play rounders while waiting for King Charles to wake up. He decided to immediately ask him for punishment. He and all his associates left my room. I, seeing that the dawn was breaking, and considering that the danger that my sister spoke about had passed, told my nurse to close the door and let me sleep to my heart's content.

The clock on the fatal tower that gave the signal

An hour later, when I was still sleeping, someone, knocking on the door with their feet and hands, shouted: “Navarre! Navarrese!" The nurse, thinking it was my husband, quickly ran to the door and opened it. On the threshold stood a nobleman named de Leran, wounded in the elbow with a sword and in the arm with a halberd. He was pursued by four shooters, who ran into my room with him. In an effort to defend himself, he threw himself on my bed and grabbed me. I tried to break free, but he held me tightly. I did not know this man at all and did not understand his intentions - whether he wanted to harm me or whether the arrows were against him and against me. Both of us were very scared. Finally, thank God, Monsieur de Nancy, captain of the guard, arrived to us, who, seeing the state I was in and feeling compassion for me, could not help but laugh. He became very angry with the shooters for their tactlessness, ordered them to leave my room and freed me from the hands of this unfortunate man, who was still holding me. I ordered him to be put in my room, bandaged and treated until he felt well.

While I was changing my shirt, as I was covered in blood, Monsieur de Nancy told me what had happened, assuring me that my husband was in King Charles's room and that he was all right. They threw a dark coat over me and the captain took me to the room of my sister Madame de Lorraine, where I entered more dead from fear than alive.

Other clocks - astrological

Here, through the hallway, all the doors of which were open, a nobleman named Burse ran in, fleeing from the shooters who were pursuing him. Three steps from me they stabbed him with a halberd. I lost consciousness and fell into the arms of Monsieur de Nancy. When I woke up, I entered the small room where my sister was sleeping. At this time, Monsieur de Miossan, the first nobleman from my husband’s entourage, and Armagnac, my husband’s first servant, came to me and began to beg me to save their lives. I hurried to King Charles and the Queen Mother and threw myself at their feet, asking them for this. They promised to fulfill my request..."

The events of St. Bartholomew's Night were condemned even by Ivan the Terrible, who himself never stood on ceremony with his enemies. From the king’s letter to Emperor Maximilian II: “And what, dearest brother, do you mourn the bloodshed that happened to the King of France in his kingdom, several thousand were beaten to the point of mere babies; and it is fitting for the peasant sovereign to mourn that the French king committed such inhumanity over so many people and shed so much blood without reason.”

Only the King of Portugal expressed his congratulations to Charles IX after the bloody events:

“To the greatest, most powerful and most Christian sovereign Don Charles, king of France, brother and cousin, I, Don Sebastian, by the grace of God king of Portugal and the Algarves, from one sea to another in Africa, lord of Guinea and conquests, navigation and trade in Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia and India, I send my great greetings, as to those whom I greatly love and respect.

All the praises that I could offer you are due to your great merits in fulfilling the sacred and honorable duty that you have undertaken, and directed against the Lutherans, the enemies of our holy faith and the opponents of your crown; for faith did not allow us to forget many manifestations of family love and friendship that were between us, and through you commanded us to maintain our connection in all cases when it was required. We see how much you have already done, how much you are still doing, and what you embody daily in the service of our Lord - preserving the faith and your kingdoms, eradicating heresies from them. All this is your duty and reputation. I am very happy to have such a king and brother who already bears the name of the Most Christian, and could now earn it anew for myself and all the kings who are their successors.

That is why, in addition to the congratulations that Joan Gomes da Silva from my council, which is at your court, will convey to you, it seems to me that we will be able to unite our efforts in this matter, which is so due to both of us, through the new ambassador, whom I am now committed to I attach; which is Don Dionis Dalemcastro, senior commander of the Order of Our Lord Jesus Christ, my very beloved nephew, whom I send to you, a man in whom, due to his qualities, I highly trust and in whom I ask you to place full and heartfelt confidence in everything that I need to tell you , highest, most powerful, most Christian sovereign, brother and cousin, may our Lord keep your royal crown and kingdom under his holy protection.”

King Charles claimed that he did not expect such bloodshed. “Even my beret didn’t know about anything.”- said the king.

According to another version of the chroniclers, the king approved the massacres.

“This massacre appeared before the eyes of the king, who looked at it from the Louvre with great joy. A few days later he went in person to see the gallows at Montfaucon and the corpse of Coligny, who was hanged by the feet, and when some of his retinue pretended that they could not approach because of the stench of the corpse, “The smell of a dead enemy,” he said, “is sweet.” and pleasant."

Arrest of the Huguenot

“On the said day, the most Christian king, dressed in his royal robes, appeared at the palace and announced to parliament that the peace he had concluded with the Huguenots, he was forced to conclude for the reason that his people were exhausted and ruined, but that at the present time , when God granted him victory over his enemies, he declares that the edict that was issued in commemoration of the said peace is invalid and meaningless, and that he wishes that the one that was published before and according to which no other faith than the Catholic, will be observed. apostolic and Roman, cannot be confessed in his kingdom.”

Thanks to the St. Bartholomew's massacre, Catherine de' Medici gained the special love of her subjects. In total, the good Catholics plundered about one and a half million gold pieces.

Catherine de' Medici

“...The tragedy continued for three whole days with bursts of unbridled rage. The city has hardly calmed down even now. A huge loot was looted: it is estimated at one and a half million gold ecus. More than four hundred nobles, the bravest and best military leaders of their party, perished. An incredibly large number of them showed up, well provided with clothing, jewelry and money, so as not to lose face at the wedding of the King of Navarre. The population became rich at their expense.”

"In the morning, at the entrance to the Louvre"

“The people of Paris are happy; they feel that they have been comforted: yesterday they hated the queen, today they glorify her, declaring her the mother of the country and the custodian of the Christian faith.”- wrote a contemporary of the events.

In total, about 30 thousand people died for the good of the kingdom. Two years after the bloody events, King Charles IX died in the arms of Catherine de Medici. Presumably he was poisoned. The queen gave the poisoned book to her enemy Henry of Navarre. Not knowing about the poison, Henry gave the book to “cousin Charles” to read... So the queen unwittingly killed her own son.

Coat of arms on Catherine de Medici's favorite church. We have a specialist for coats of arms