Dmitry and Khariton Laptev biography. Biography

Famous explorer of northern Asia; in 1718 he enlisted in the navy's midshipmen; in 1737 he was assigned to a large northern expedition, which described and photographed for the first time the shores of the Arctic Ocean from the White Sea to the river. Kolyma. On June 9, 1739, L. left Yakutsk, and on the 21st he was already in the ocean and, making an inventory of the shore, wintered in Khatanga Bay. On July 12, 1740, on the same boat-boat, he went further to the west; after a difficult swim along the lip, he went to sea only a month later, but here he encountered even more difficult obstacles; finally, the ice finally crushed the ship and the crew and officers had to get to the shore on the ice; with difficulty they returned to their winter quarters last year. In view of two unsuccessful attempts to go around the Taimyr Peninsula by sea, L. decided to describe its shores by land, moving on dogs. For this purpose, he equipped three separate expeditions, and L. himself described part of the coast from the mouth of the river. The Taimyrs are somewhat towards B and 3. In 1742, he traveled again to the mouth of the Taimyr, thinking of taking part in the inventory of the extreme north. part of the peninsula, but, due to lack of provisions, returned to Turukhansk and from there went to St. Petersburg with reports. He died in 1763, with the rank of Ober-Ster-Kriegs-Commissar of the Fleet.

(Brockhaus)

Laptev, Khariton Prokofievich

traveled the Arctic Ocean, lieutenant, † 1768.

(Vengerov)

Laptev, Khariton Prokofievich

lieutenant, traveled across the Arctic Ocean northeast of Siberia, 1739-40, † 1768 chief commissar of the Baltic Fleet.

(Polovtsov)

Laptev, Khariton Prokofievich

(born unknown - died 1763) - Russian. Arctic explorer, began serving in the navy in 1718 as a midshipman. In 1737 he was promoted to lieutenant and appointed head of the Great Northern detachment. expedition to photograph the sea coast west of the river. Lena. In 1739 he sailed on the double-boat "Yakutsk" from the Lena to Cape Thaddeus, where he was stopped by ice. For the winter he stood at the mouth of the river. Prodigal (right tributary of the Khatanga River). In 1740, during a new attempt to go around the Taimyr Peninsula, the ship was crushed by ice near the coast at 75 ° 26 "N. In 1741-42, carrying out work in sleigh parties, L. with his assistants S. Chelyuskin (see) and N. Chekin completed the route survey of the Taimyr Peninsula, which served as the only source for depicting it on maps until the end of the 19th century. The description of the coast from the Lena to the Yenisei compiled by L. was of great value. After the end of the expedition, L. continued to serve in the Baltic Fleet. named in honor of L.: the sea coast between the Pyasina River and Taimyr, two (the eastern-eastern cape of the island of the pilot Makhotkin, a cape on the eastern shore of the Chelyuskin Peninsula; in honor of Kh. P. Laptev and D. Ya. Laptev ( cm.) called the Laptev Sea.

Works: The shore between the Lena and the Yenisei, "Notes of the Hydrographic Department of the Maritime Ministry", 1851, part 9.

Lit.: See lit. to the article Laptev Dmitry.

On December 20, 1737, the Admiralty Board reviewed Bering’s reports with the materials attached to it and, disagreeing with him, decided to continue mapping the sea coast in this area. Both detachments were given new deadlines for completing the work and ordered to continue it “to completion in another or a third summer in the same way without the slightest loss of convenient time; and if some impossibility does not allow it to be completed in the third summer, then in the fourth summer try with utmost zeal and diligence to ensure that the work is completed.”

At the same time, the Admiralty Board approved new, more detailed and accurate instructions for detachment commanders. According to this instruction, the detachments had to prepare for campaigns in advance, and immediately, as soon as the ice conditions allowed, without wasting precious summer time, set off. The detachment commanders were instructed to wait for changes in the ice situation directly in those places where it would not be possible to overcome the ice, and at the slightest opportunity to move on. In addition, the instructions recommended stopping for the winter as close as possible to those points where winter would overtake the ships. This was supposed to save the troops from wasting time moving along already known shores.

At the same meeting, the Admiralty Board appointed Khariton Prokofievich Laptev as head of the detachment that mapped the sea coast between the mouths of the Lena and Yenisei. Subsequent events showed that the board was not mistaken in its choice, sending this comprehensively educated naval officer, who possessed exceptional energy, willpower and courage, to the most difficult part of the expedition’s work.

H.P. Laptev had solid experience in the navy. Before his appointment to the expedition, he had already sailed on various ships for nineteen years.

But, despite Laptev’s impeccable attitude towards his duties, his service did not go smoothly. In 1734, during the operations of the Russian fleet near Danzig, the frigate Mitau, sent for reconnaissance, on which midshipman Khariton Laptev served, was fraudulently captured by the French fleet, which had acted a few days earlier on the side of the enemy, which the Russian commander did not know frigate. All Mitau officers, including X. Laptev, were put on trial for surrendering the ship to the enemy without a fight and were sentenced to death. After an additional investigation into the circumstances of the case, carried out by decision of the government, it became clear that neither the commander nor the other officers of the frigate were guilty of surrendering the ship to the French, and therefore on February 27, 1736, they were all pardoned.

In 1736, Laptev took part in the summer voyage of the Baltic Fleet, and then was sent to the Don “to find the most convenient place for the ship’s structure.” The following year, Laptev was appointed commander of the court yacht "Dekrone", but upon learning that officers were needed to participate in the Great Northern Expedition, he asked to be appointed there. Obviously, the life of a polar explorer, full of hardships, attracted Khariton Laptev more than the calm and honorable service at court.

In February 1738, Khariton Laptev’s cousin, Dmitry Yakovlevich Laptev, the head of the detachment that mapped the coast east of the Lena, arrived in St. Petersburg with journals, reports and maps. He provided the Admiralty Boards with completely new information about working conditions near the mouth of the Lena, in particular about ice accumulations, which are observed in the same places from year to year and impede the movement of ships. Dmitry Laptev proposed mapping the coast in such areas, moving on land.

Having read the report of Dmitry Laptev, the Admiralty Board on March 3, 1738 confirmed its decision on a four-year period of work for both detachments, but gave Khariton and Dmitry Laptev completely new instructions regarding how to complete the task.

Best of the day

The detachment commanders were instructed, if the ice did not allow them to complete the voyage in the first and second summers, to send the ships with part of the teams to Yakutsk or put them in a convenient place for the winter, and continue working with the rest of the people, moving along the coast.

The detachments were instructed to pay attention to the places where standing ice would be encountered, determine how far it extended, note the position of the floating ice, its concentration, the duration of its stay near the shore, as well as places “where there is no strong obstacle from the ice.” The detachments had to determine the possibility of navigation in the work area, measure depths, find river mouths and other convenient places for anchorage and wintering of ships.

The decision to continue work from the shore if it was impossible for ships to move by sea was allowed to be made by the detachment commanders only after a consultation with their officers.

The Laptevs left St. Petersburg together. In Kazan they received rigging for ships, in Irkutsk - provisions, things for gifts to residents of the Siberian coast and money. Khariton Laptev demanded that the Irkutsk office prepare deer and dogs on the coast in case his detachment had to conduct an inventory from the land, and resettled two families of industrialists from the mouth of Olenek to the mouths of Anabar, Khatanga and Taimyra, ordering them to engage in harvesting fish and building houses In case the detachment wintered at these points, at the same time Khariton Laptev informed the office of Turukhansk about the need to send provisions for his detachment to the mouth of the Pyasina River in the summer of 1739.

At the beginning of March 1738, the Laptevs arrived in Ust-Kut, located in the upper reaches of the Lena. Small river vessels were built here for the expedition. In the spring, when the river opened up, property and provisions for the detachments were delivered to Yakutsk on these ships.

On May 25, 1739, Khariton Laptev arrived in Yakutsk. The double boat "Yakutsk" was already ready for the trip. Her crew consisted of forty-five people; Almost all of them were participants in Pronchishchev’s voyage.

Having finally put everything in order, Khariton Laptev took his ship down the Lena on June 5; boarders with provisions went with him.

In the Lena delta, Laptev managed to find the entrance to the Krestyatskaya channel and by July 19 he reached the seashore.

On July 21, "Yakutsk" headed west to Khatanga Bay, and Laptev ordered the planks, not adapted for sailing on the open sea, to be led to the mouth of Olenek and stored provisions in Pronchishchev's old winter quarters.

Near the mouth of Olenek, the ship entered the “great ice.” The dubel-boat sailed under sails and oars, the crew pushed the ice floes with poles, and sometimes made a path in the ice with picks. A week later, on August 28, Laptev reached the eastern entrance to the strait separating Begichev Island from the mainland. The strait was clogged with motionless ice.

It seemed to the surveyor Chekin, who was sent ashore for an inventory, that the ice was pressed against the shore that closed the bay from the west; therefore, he mistook the strait for a bay open to the east, and Begichev Island for a peninsula. The bay was put on the map under the name Nordvik.

Moving away from the Nordvik "bay", the "Yakutsk" headed north to go around the "peninsula" and enter the Khatanga Bay. In an effort to avoid being compressed by the ice, pressed to the shore by the wind, Laptev sailed the boat into some cove, where he waited for five days for the ice situation to improve.

Having broken through the ice, Laptev entered the Khatanga Bay on August 6. A winter quarters could be seen on the western shore of the bay. Laptev decided to take some of the provisions ashore in case he had to spend the winter in this place. But before this intention could be realized, the north wind blew again, driving ice into the bay.

Again we had to look for shelter, and Laptev took the boat-boat south along the coast. Soon another winter hut appeared. Near it, the Yakutsk entered the mouth of a small river and stood there for a whole week, which was spent unloading part of the provisions ashore.

On August 14, when the wind changed direction and drove away the ice, Laptev led the ship along the coast to the north. When leaving the Khatanga Bay, an island was discovered called Transfiguration Island.

On August 17, the Yakutsk passed the Peter Islands and went along the coast to the west. The next day we had to stand due to ice at the Thaddeus Islands, and then move forward in the ice. Only on August 21, "Yakutsk" approached the high Cape Thaddeus. On one side of the cape the coast stretched to the southwest, and on the other to the west. The further path was blocked by motionless ice. It was not possible to determine the boundaries of the ice due to dense fog. Therefore, Laptev sent Chekin on dog sleds to find out how far the ice extended to the west, and Chelyuskin to Cape Thaddeus to set up a lighthouse there. Returning twelve hours later, Chekin reported that the ice was impassable.

Frost has set in. I had to think about wintering. An inspection of the shore yielded disappointing results: there was no driftwood to build housing. At a consultation organized by Laptev on August 22, it was decided to return to Khatanga Bay. By August 27, "Yakutsk" barely made its way to the winter quarters, where it was located at the beginning of the month. Laptev took the ship further south. Entering Khatanga, he reached the mouth of its right tributary - the Bludnaya River, where several families of deerless Evenks lived.

Here the detachment built a house and stayed for the winter.

By September 25, Khatanga became. The hard winter work of the detachment began. Back in the fall, Laptev sent soldier Konstantin Khoroshikh to Turukhansk with a demand that the voivode’s office deliver provisions for the winter and provide reindeer and dog sleds. Now Laptev used these sleds to transport the provisions that had previously been unloaded at the mouth of Olenek and on the shore of the Khatanga Bay. Local residents were involved in this work. The winterers did not have enough driftwood for fuel, and had to walk several miles from the winter hut every day to get it.

To protect the team from scurvy, Laptev introduced fresh frozen fish into the daily diet, thanks to which there was not a single case of scurvy throughout the winter.

Laptev continued to collect information about the northern region during the winter. From the stories of local residents - Russians, Tavgians, Yakuts and Evenks - he learned that no one lives permanently north of the Bolshaya Balakhnya River, although there is a winter hut on the sea coast, where industrialists come during hunting.

To explore the coast from the mouth of the Pyasina to Cape Thaddeus, Laptev at the end of October 1739 sent boatswain* Medvedev with one soldier to the mouth of the Pyasina on a sleigh. Having reached the mouth by the beginning of March 1740, Medvedev set off along the seashore to the northeast. But severe frosts and strong winds prevented him from carrying out the necessary work, and, having traveled along the coast for only about forty miles, he was forced to return to the detachment.

On March 23, 1740, Chekin left his winter quarters with the task of describing the coast between the mouths of the Taimyr and Pyasina. Since it was then believed that Thaddeus Bay was the mouth of the Taimyr, Chekin, therefore, had to move towards Medvedev. Laptev learned that the latter was returning back to wintering only at the end of April, when Medvedev arrived at the detachment. One soldier and one Yakut, who was settled at the mouth of the Taimyr, went with Chekin. Chekin had two teams of dogs at his disposal.

Chekin reached the source of the Taimyra River and followed it to the mouth, and then along the seashore to the west. He walked about 100 miles and reached the point where the coast turns south. Having placed a navigation sign here - a pyramid of stones - Chekin was forced to turn back, since “there was very little food for himself and for the dogs, with which it was dangerous to go further to an unknown place.”

On May 17, Chekin and his companions returned to their winter quarters on foot, “in extreme need,” having lost almost all their dogs from lack of food and abandoned the sledges.

In April of the same year, cartography of the coast between the mouths of the Pyasina and Taimyra was carried out by the navigator Sterlegov sent by Minin. Apparently, he arrived at the mouth of the Pyasina shortly after Medvedev left there. Chekin and Sterlegov moved towards each other, and both turned back almost at the same time. There were about 200 kilometers between the extreme points they reached.

Preparing for the next voyage, Laptev decided to stock up on food for his squad. For this purpose, he sent two industrialists to the mouth of the Taimyr River to catch and stock fish.

Khatanga was opened on June 15, but due to ice accumulated in the Khatanga Bay, the dubel-boat was able to leave the river only on July 13. It took another month for the Yakutsk to overcome the ice in the bay and go to sea.

During the first 24 hours after leaving Khatanga Bay, the ship moved quite far to the north. On the morning of August 13, at 75°26" north latitude, the Yakutsk approached the edge of unbroken ice, stretching from the shore to the northeast. Laptev directed the ship along the edge. The wind, which soon changed, began to catch up with the ice, and the boat-boat got stuck. The wind grew stronger, the ice As the vessel became more and more compressed, a leak appeared.

The crew continuously bailed out water and used logs to protect the sides of the boat from the ice pressure. But this did not save Yakutsk. Soon the ice broke the stem, and by the morning of August 14 the ship was in completely hopeless condition. Laptev ordered a heavy cargo to be unloaded onto the ice, hoping to ease the situation of the double boat: guns, anchors, provisions and other cargo were removed, and then, when it became clear that the ship could not be saved, people abandoned it.

A day later, when sufficiently strong ice had formed, Laptev led the team ashore. The sailors carried provisions; The sleds of the dog sled on the doubel-boat were loaded to the limit with provisions. Having warmed up by the fire, the tired people began to build a dugout and transfer the cargo remaining near the ship to the shore.

This work continued until August 31, when the ice that began to move destroyed the Yakutsk double boat and the cargo remaining on the ice.

It was not possible to move south to populated areas due to ice drift on the rivers. Only on September 21 the detachment was able to set off. On the fifth day he reached the winter quarters of Konechnoe, where the industrialists were located. Twelve patients remained here, and the rest took advantage of the transport of industrialists and by October 15 arrived for the winter near the Bludnaya River. Soon the industrialists, whom Laptev had sent in the spring to the mouth of the Taimyr River to stock up on fish, also arrived for the winter. They managed to successfully complete the task within a short summer.

The experience of Pronchishchev's voyages in 1736, as well as Laptev's own research in 1739 and 1740, convinced him that it was impossible to sail along the coast between the mouths of Pyasina and Taimyra. Moreover, the only ship of the detachment, the Yakutsk, was lost. There was only one possibility left - to carry out cartographic work from land.

On November 8, 1740, Laptev arranged a consultation with his subordinates - Chelyuskin, Chekin and Medvedev. The council agreed with Laptev’s opinion that “the state of the ice and the depth of the bays and rivers cannot be described at any other time, given the local climate, but to start in June and follow through the months of July and August, observing their condition, because at that time... the ice breaks both on the sea, and in the lips and in the rivers, and [in] other times stand still." Therefore, it was decided to describe the coast, which had not yet been mapped, from land.

But it was impossible to carry out an inventory from the shore in the summer, since dog and reindeer sleds, which served as the only means of transport, could move across the tundra only in winter. Taking this into account, the council decided to carry out mapping in winter, although the results could be less accurate and complete.

On November 25, Laptev sent all these decisions, along with his report, to the Admiralty Boards for approval. Giving a number of arguments in favor of the council’s decision, he said that he could begin work in April 1741 and that he would send people free from work to the Yenisei “to a residential place where there is enough food, and also healthy places.”

Laptev’s envoy, sailor Kozma Sutormin, quickly delivered the detachment’s report and journals to St. Petersburg at that time, and already on April 7, 1741, the Admiralty Board began considering these materials. She agreed with the decision of the council and allowed an inventory of the seashore to be made from land.

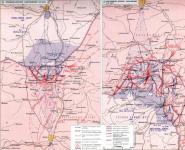

Laptev began to implement his plan long before receiving the order from the Admiralty boards. He decided to make an inventory; in three batches at once. One party was supposed to work between the mouths of Khatanga and Taimyra, the second - from the mouth of Pyasina to the east before meeting with the third party, moving from the mouth of Taimyra to the west. This distribution of routes is explained by the fact that at that time Laptev still believed that the mouth of the Taimyr River was located in the area of Cape Thaddeus, that is, much east of its true position. Therefore, the section of coast from Khatanga to Taimyra seemed much shorter than it actually is, and the section between Taimyra and Pyasina, on the contrary, was very large.

Relatively few people were required to complete the land inventory. Laptev left with him Chelyuskin, Chekin, one non-commissioned officer, four soldiers and a carpenter, and sent the rest in two groups (one on February 15, the other on April 10) on reindeer to Dudinka on the Yenisei. Part of the property rescued from the double boat was sent with the second group. The heaviest cargo remained in the warehouse at the wintering site.

At the same time, Laptev received a message from the Turukhansk voivodeship office that his requirements regarding the preparation of dog food at the mouth of the Pyasina and in other “convenient places” on the coast, sent to the office in the fall of 1740, had been fulfilled. However, this news turned out to be false: there were no food reserves anywhere, and all parties of Laptev’s detachment experienced extreme difficulties due to this.

On March 17, 1741, the second party, Chelyuskin and two soldiers, left the detachment’s winter quarters on three dog sleds.

On April 15, the first party left the detachment’s winter hut - Chekin with soldiers and a Yakut, and on April 24 - the third party, led by Khariton Prokofievich Laptev himself.

Six days later, Laptev’s party reached Lake Taimyr, crossed it and, reaching the source of Taimyr, moved along its valley further to the north. On May 6, Laptev arrived at the mouth of the Taimyra River and became convinced that it was located significantly west of Thaddeus Bay. This forced him to change his work plan. Seeing that Chekin had to make an inventory of the coast over a much larger area than he had expected, Laptev decided to go towards Chekin, that is, to the east, and not to the west. Having mapped the coast, Laptev approached a place where a long-term accumulation of ice had formed. He discovered this accumulation through various layers of ice that had formed over a number of years. In those places where “the ice breaks in summer,” in winter it was clear “that in some places there are fresh hummocks.” Most of the hummocks were near the shore, and far from it there were ice floes “with summer thawed patches.” Summarizing his observations, Laptev came to the conclusion that in summer the ice cover breaks up, and the accumulation of hummocks occurs where moving ice encounters an obstacle - stationary ice or the shore.

This conclusion of H.P. Laptev was confirmed by later studies. It is still true today.

On May 13, having reached latitude 76°42", Laptev was forced to stop due to a blizzard and fog. In addition, he and the soldier accompanying him began to experience snow blindness. Further advancement could only worsen the disease. After waiting out the bad weather, Laptev decided to return to the mouth Taimyr, where he expected to find food.

However, there was no food at the mouth of the Taimyr River, where Laptev arrived on May 17. Arctic foxes and polar bears ate the fish stored here, and Chekin needed the food supply brought here to feed his dogs.

Thus, Laptev could not take anything for his four teams. Therefore, he decided to go west, towards Chelyuskin, hoping to receive “help with food” from him.

On May 19, when the pain in his eyes had subsided somewhat, Laptev set off. On May 24, he approached the cape, from which the coast turned south. Having determined the latitude of the cape (76°39") and placing a noticeable sign on it, Laptev moved on.

On June 1, Laptev met with Chelyuskin near the sign erected in 1740 by Sterlegov at the end point of his route. Chelyuskin’s dogs were also exhausted, since he and he had little food to spare. Only a successful hunt for polar bears helped the travelers.

Spring was approaching, and Laptev, afraid of being stuck on the deserted seashore for a long time, was in a hurry to get to the winter quarters at the mouth of the Pyasina River. By June 9, he, together with Chelyuskin, reached the mouth of the Pyasina, where he was forced to wait out the flood. Only a month later they managed to go by boat up the river. The path was extremely difficult, but, fortunately, the detachment soon met the Nenets wandering in the lower reaches of Pyasina and by the end of July reached Golchikha with them on reindeer, and then on a passing ship up the Yenisei to Dudinka.

Chekin was already here. It turned out that he only managed to reach latitude 76°35", that is, to the Peter Islands. He was unable to proceed further due to snow blindness.

In Dudinka, Laptev learned that part of his detachment, sent from Khatanga on April 15, had not yet arrived here. A sailor who came to Dudinka said that when their group reached the Dudypta River on reindeer, the owners of the reindeer - the Tavgians - dropped their loads and went on a summer nomad in the tundra. Having obtained boats, the sailors went down the Dudyptedo Pyasina. Here they remained to wait for help. Laptev sent the Nenets and Tavgians gathered in Dudinka after them.

When Laptev summed up the work of all three parties, it turned out that the cartographic work had not been completely completed, since the section of coast between Cape Thaddeus in the east and the extreme point in the west, which he himself had reached, remained unmapped. Laptev postponed the filming of this section until next winter, but in the meantime he decided to go to Turukhansk to request from the authorities the necessary transport for a trip to the coast, provisions for people and food for dogs, and also to arrange winter quarters for the detachment’s people free from work.

On September 29, Laptev with all the people who were with him in Dudinka arrived in Turukhansk, and on September 15, part of the detachment taken from Lake Pyasina arrived there. For the first time this year, the entire detachment gathered in Turukhansk. Preparations for the last campaign began. By December all preparations were completed. On December 4, 1741, Chelyuskin with three soldiers left Turukhansk on five dog sleds, and on February 8, 1742, also on five sleds, Kh.P. himself. Laptev.

Chelyuskin headed to the mouth of Khatanga, and from there to the north, along the coast. Laptev's path was more complex and lengthy. Having reached Dudinka along the Yenisei, Laptev’s group turned east and through the tundra reached Pyasina, and then along it to Dudypta. From here Khariton Laptev turned north, crossed the Bolshaya Balakhnya River and approached the southern shore of Lake Taimyr. The further path lay on the ice across the lake and along the Taimyr River to its mouth.

Arriving at the mouth of the Taimyr in early May, Laptev sent a soldier Khoroshikh and one Yakut with a supply of provisions and dog food to meet Chelyuskin. At this time, Chelyuskin had already reached the northernmost cape of Asia and was mapping the northern coast.

On May 15, Chelyuskin met with the people sent by Laptev, and together with them went to the mouth of the Taimyr River to meet with the head of the detachment, since he had completed the inventory of the site by that time. From the mouth of the Taimyra, Khariton Laptev and Chelyuskin hurried to Turukhansk, and from there the entire detachment went to Yeniseisk, mapping the banks of the Yenisei along the way. On August 27, 1742, the detachment arrived at its destination. The task assigned to him was completed.

Now it was already possible to present to the Admiralty Boards a new, more accurate map of the Taimyr Peninsula. Of course, the information collected by Khariton Laptev’s detachment could not be considered absolutely accurate. He himself and his expedition comrades knew this. They had imperfect instruments and methods for determining longitude, which gave very approximate results. At that time, there was not even a chronometer (this device was invented only in 1772). In addition, Khariton Laptev’s detachment worked in winter, when the snow cover did not allow establishing the exact outlines of the coastline.

All this determined the errors on the map compiled by Laptev, on which the eastern coast of the Taimyr Peninsula is plotted much further east than it actually is, and the islands lying north of the Taimyr Peninsula are designated as capes (for example, Cape North-West).

However, all this in no way detracts from the merits of Khariton Laptev, the first explorer of one of the harshest areas of the Arctic Ocean.

September 13, 1743 H.P. Laptev submitted a report to the Admiralty Board, in which he outlined the results of the detachment’s work and his personal notes, which are of great scientific value. Laptev explained that he compiled these notes “for information” to his descendants, that he included in them what he considered “indecent to add to the journal,” as not related to the work performed by the detachment. He called them "The shore between the Lena and the Yenisei. Notes of Lieutenant Khariton Prokofievich Laptev."

The notes consisted of three parts. In the first part, he gives a brief description of the coast from Stolb Island on the Lena River to the mouth of the Yenisei. In a concise form, but quite fully, he described the nature of the coast, coastal depths, “decent places”, their soil, the state of the ice, the mouths of rivers, their width and depth, data on the ebb and flow of the tides and other information very important for science are given.

The second part describes the rivers sequentially, starting from the Lena and further west to the Yenisei. Each river is given a characteristic - where it flows from, how long it is, where the forest ends and the tundra begins, in what places people live and what they do. The following describes Lake Taimyr. It tells “about the tundra lying near Lake Taimursky”, “about mammoth horns” (that is, about fangs). Much space in this part is devoted to the life, activities, morals and customs of the inhabitants of Turukhansk.

In the third part, entitled “Finally, this description is appended about the nomadic peoples near the northern Siberian places in Asia, in what superstition they contain themselves, and about the state of something about them,” Khariton Laptev systematizes ethnographic information about the peoples inhabiting the Taimyr Peninsula.

These observations are fully confirmed by modern data. A characteristic feature of the ethnographic descriptions of H.P. Laptev is the absence of arrogance towards representatives of northern peoples. Khariton Laptev speaks with praise, for example, of the Evenks - “Tungus”. Reporting that local residents eat raw meat and fish, he does not express any contempt for them for such “savagery.” On the contrary, Laptev notes the need for food in northern places with raw planed meat, which “does not allow a sick person to develop scurvy, but at the same time drives out old ones; even better is the effect of frozen planed meat, deer, and the same disease is treated.”

The notes of Khariton Prokofievich Laptev, which are of enormous scientific value, were highly appreciated by leading scientists in Russia and other countries.

Khariton Prokofievich Laptev also continued to serve in the navy after the expedition. In the spring of 1757, he was assigned to the Navigation Company to train future navigators. Until 1762, Laptev held combat positions, commanding ships in the summer months. By this time he had the rank of captain 1st rank. On April 10, 1762, Laptev was appointed Ober-Ster-Kriegs-Commissar of the Fleet. On December 21, 1763, he died.

The Motherland has not forgotten the names of the heroic participants of the Great Northern Expedition - the leaders of the detachment that described the coast between the mouths of the Lena and Yenisei. Their names remained on the world map, reminding descendants of the scientific feat of their compatriots.

On the eastern coast of the Taimyr Peninsula, somewhat north of the Komsomolskaya Pravda Islands, there is Cape Pronchishcheva. The eastern coast of this peninsula, stretching from the Peter Islands to the entrance to the Khatanga Bay, is called the coast of Vasily Pronchishchev.

In 1913, approximately in the middle of the coast of Vasily Pronchishchev, a large bay was discovered by a Russian expedition on the icebreakers "Taimyr" and "Vaigach", which it called Maria Pronchishcheva Bay. On the sea coast between the mouths of the Anabar and Olenek rivers there is a low mountain range called Pronchishchev.

The part of the western coast of the Taimyr Peninsula, lying between the mouths of the Pyasina and Taimyr, is called the Khariton Laptev coast.

Opposite the middle part of the Kharitov Laptev coast, closer to the mouth of the Taimyr, in a complex archipelago lies the island of the pilot Makhotkin. Its two northeastern capes are called: one Cape Laptev, the other Cape Khariton, in honor of Khariton Laptev. On the eastern coast of the Taimyr Peninsula, opposite the Komsomolskaya Pravda islands, in the place where the coast turns sharply to the west towards Theresa Claveness Bay, Cape Khariton Laptev juts out into the sea.

These names remind us of the brave Russian naval officers who, more than two hundred years ago, led the first exploration of the northernmost section of the Asian coast.

Khariton Prokofievich Laptev (1700 - 12/21/1763), Russian navigator and Arctic explorer, cousin Dmitry Yakovlevich Laptev.

Khariton Prokofievich Laptev in December 1737 was appointed head of the Great Northern Expedition detachment with instructions to survey and describe the Arctic coast west of Lena to the mouth of the Yenisei. In 1743 he returned to St. Petersburg, having successfully completed the task, and continued to serve on the ships of the Baltic Fleet (since 1762 - Ober-Ster-Kriegs-Commissar). Laptev's reports and reports of 1739-1743 contain valuable information about the progress of the work of the northern detachment of the Great Northern Expedition, about the hydrography of the coast of the Taimyr Peninsula.

Laptev Khariton Prokofievich (?-1763) - captain 1st rank, participant of the Great Northern Expedition, Ober-Stern-Kriegskomissar (since 1762).

In 1734, he sailed as a midshipman in the Baltic Sea on the frigate Mitau, which was captured by a French squadron. After the exchange of prisoners, the commander and all the officers of the frigate, including Laptev, were sentenced to death for surrendering the ship to the enemy without a fight. When it became clear that the convicts were not guilty, all of them were returned to their previous ranks.

In 1737, he was assigned to the Great Northern Expedition to survey the shores of Siberia from the river. Lena to the river Yenisei. He participated in the expedition by water until 1740, when the dowel-boat "Yakutsk" was covered with ice. Then he continued the expedition overland. By 1742, he completed an inventory of the entire continental coast of the sea, called the Laptev Sea in Soviet times.

Book materials used: A.A. Grigoriev, V.I. Gasumyanov. History of Russian state reserves (from the 9th century to 1917). 2003.

LAPTEV Khariton Prokofievich (1700–1763/64), Russian navigator, captain of the 1st rank (1753), one of the discoverers of the Arctic, participant of the Great Northern Expedition. As head of the Lena-Khatanga detachment, together with surveyor Nikifor Chekin and navigator S.I. Chelyuskin in 1733–42. made the first instrumental survey of more than 3.5 thousand km of the coast of North Asia between the Lena and Yenisei, including both shores of the Khatanga Bay (approx. 500 km). Identified the Taimyr Peninsula (the largest in Russia) with a lake, river and Byrranga mountains, discovered the Bolshoy and Maly Begichev islands, Nordvik Bay, a number of bays and capes, as well as islets included in the Nordenskiöld archipelago, mistakenly taken for northern . mainland protrusion. He discovered the seaside, which was later named the Khariton Laptev Coast, and correctly mapped the south. border of the North Siberian Lowland for 1.5 thousand km and collected the first information about the local population - the Tavgians (Nganasans). Thanks to the diet of stroganina (frozen fish), introduced by the commander, during three winterings there was not a single case of scurvy. Upon returning to St. Petersburg (1743), Laptev submitted a report to the Admiralty Board, in which he outlined the results of the detachment’s work. He prepared for printing the first pilotage of the Kara and Laptev seas, published only in 1851. Later he participated in the preparation of the General Map of the Russian Empire (1746). Three capes bear his name (except for the Taimyr coast); The sea is named after cousins Khariton and Dmitry Laptev.

Modern illustrated encyclopedia. Geography. Rosman-Press, M., 2006.

Dmitry Yakovlevich and Khariton Prokopyevich Laptev (XVIII century)

The Russian Navy gave our country not only wonderful naval commanders and scientists, but also a whole galaxy of brave travelers and explorers. The latter include cousins, fleet lieutenants Dmitry Yakovlevich and Khariton Prokopievich Laptev, remarkable Russian polar explorers, participants in the Great Northern Expedition.

Peter I laid the foundation for one of the most ambitious scientific expeditions of all time - the Great Northern Expedition. The first, so-called Kamchatka, expedition set out to determine whether Asia and America are connected by an isthmus or separated by a strait. Commander was appointed head of the expedition Vitus Jonassen Bering, a Dane by origin, who was accepted by Peter I into service in the Russian fleet in his youth and served in it for 37 years.

This expedition, successfully carried out from 1725 to 1730, was the prologue to the second stage of work - the Great Northern Expedition, which worked from 1733 to 1743 and was led until 1741 by V. Bering.

The task of the expedition was to study and inventory the Russian shores from Yugorsky Shar to Kamchatka and put them on maps. Up to 600 people took part in it, divided into several detachments.

Two of them, under the command of lieutenants Pronchishchev and Lasinius, were supposed to, leaving Yakutsk along the Lena into the sea, examine and make an inventory of the coast - Pronchishchev from the Lena to the Yenisei and Lasinius - from the Lena to Kolyma and further to Kamchatka.

The units did not complete their task.

Peter Lasinius, Swede by nationality, was accepted into Russian service in 1725. He sailed a lot and was a competent navigator. Lasinius volunteered for the expedition. Bering appointed him head of a detachment that was supposed to describe the coast from the mouth of the Lena to Kamchatka. The detachment had a built in Yakutsk bot "Irkutsk""Eighteen meters long, five and a half meters wide, with a draft of two meters.

Lasinius and his detachment left Yakutsk on June 29, 1735, simultaneously with Pronchishchev’s detachment. Both detachments arrived on August 2 at Stolb Island, located at the beginning of the Lena delta.

On the second day, the Irkutsk, having passed the Bykovskaya channel, reached the seashore. Two days later, after waiting for a fair wind, Lasinius took his ship out to sea.

Navigation was made difficult by large accumulations of ice and unfavorable winds. Therefore, already on August 18, Lasinius brought the boat to the mouth of the Kharaulakh River, deciding to spend the winter here.

The team quickly built a house from driftwood lying on the shore.

Counting on another two years of work, Lasinius decided to save food and halved the ration. Chronic malnutrition and ignorance of anti-scorbutic drugs led to a massive incidence of scurvy, which claimed the lives of thirty-eight people. Lasinius himself was one of the first to die.

Only 9 people survived this terrible winter. To save 9 people, Commander Bering sent a special expedition under the command of navigator Shcherbinin, who took them to Yakutsk. The boat "Irkutsk" remained at the mouth of Kharaulakh. Bering appointed one of his closest assistants, Lieutenant Dmitry Yakovlevich Laptev.

Dmitry Yakovlevich Laptev born in 1701 in the village of Bolotovo near Velikie Luki. In 1715, together with his cousin Khariton Laptev, Dmitry entered the Maritime Academy in St. Petersburg. After graduating from the Academy in 1718, he was promoted to midshipman and began serving in the Baltic Fleet on the ships of the Kronstadt squadron.

In 1721, Laptev received the rank of midshipman; in 1724, for special services in maritime science, he was promoted to non-commissioned lieutenant. Since 1725, the young officer served on the ship "Favourite", sailing along the Gulf of Finland. From 1727, for two years, Dmitry Laptev served as commander of the frigate "St. Jacob", and then as commander of a packet boat plying between Kronstadt and Lubeck.

Laptev's first acquaintance with the northern seas took place in the summer of 1730, when he sailed in the Barents Sea on the frigate "Russia" under the command of Captain Barsh. In 1731, Dmitry Laptev was promoted to lieutenant.

A highly educated and knowledgeable officer, Dmitry Laptev, was noticed by the Admiralty Board and included in the list of participants in the Great Northern Expedition. In July 1735, D. Ya. Laptev arrived in Yakutsk. He was instructed to lead a caravan of small river ships with the expedition's property along Aldan, May and Yudoma as close as possible to Okhotsk, build warehouses, store cargo in them, and then bring the ships to Yakutsk. Laptev successfully completed this task, guiding the ships to the Yudoma Cross.

Initially, it was planned to assign Lieutenant Laptev to the Bering-Chirikov detachment or to the Shpanberg detachment. However, in 1736, when the tragic fate of Lieutenant Lasinius’s detachment became clear, a decision was made to appoint Dmitry Laptev as the new commander of the Lena-Yenisei detachment.

Having received an order to replace the deceased Lasinius, D. Ya. Laptev formed a detachment in Yakutsk and in the spring of 1736, going out to sea along the Lena, he reached the mouth of the river in light boats. Kharaulakh, where the abandoned Irkutsk stood.

Having put the ship in order, D. Ya. Laptev returned to the river delta. Lena for loading food and equipment, delivered there in advance by boats from Yakutsk. On August 22, 1736, D. Ya. Laptev completed loading and went to sea, heading east. Heavy ice blocked the way. Just four days later, D. Ya. Laptev was forced to turn back. With difficulty he reached the Lena and, having climbed it, stood for the winter somewhat higher than Bulun.

The scurvy came again. But D. Ya. Laptev took into account the sad experience of his predecessor. He recommended to his team more air, more movement, and adequate nutrition. As a result, the winter went relatively well - everyone got scurvy, but only one person died.

In the summer of 1737, D. Ya. Laptev returned to Yakutsk to agree with Bering on a plan for further work. But Bering was no longer in Yakutsk. Here D. Ya. Laptev learned about the sad fate of Pronchishchev.

Biography

Born in 1702 in the Bogimovo estate of the Tarussky district of the Kaluga province (12 kilometers from the city of Aleksin) into the noble family of the Pronchishchevs. He was the fifth child in the family. In April 1716 he entered the Navigation School in Moscow, located in the Sukharevskaya Tower, as a student.

In 1718 he was transferred to St. Petersburg to the Naval Academy (he studied with Chelyuskin and Laptev) and became a midshipman. From 1718 to 1724, he served as a navigator's apprentice in the Baltic Fleet on the ships "Diana" and "Falk", the brigantine "Bernhardus", on the ships "Yagudiil", "Uriil", "Prince Eugene", and the gukor "Kronshlot".

In 1722 he took part in Peter's Persian campaign.

In 1727 he was promoted to navigator. Joined the commission for certification of naval ranks. In 1730 he was promoted to the rank of navigator 3rd rank. Vasily Pronchishchev serves on the packet boat "Postman", in 1731 on the ship "Friedrichstadt", on the frigate "Esperanza".

Lena-Yenisei detachment of the Great Northern Expedition

In 1733 Pronchishchev received the rank of lieutenant and took part in the Great Northern Expedition, leading the Lena-Yenisei detachment, which explored the coast of the Arctic Ocean from the mouth of the Lena to the mouth of the Yenisei.

June 30, 1735 Pronchishchev went from Yakutsk down the Lena to double boat "Yakutsk".

The Yakutsk crew consisted of more than 40 people, including navigator Semyon Chelyuskin and surveyor Nikifor Chekin.

But the name of Vasily Pronchishchev stands out especially in this series, because he went on a voyage with his wife, who became the world's first female polar explorer. Most likely, they knew each other since childhood - their fathers once served in the same regiment, and their family estates were located next door. Vasily Pronchishchev was born in 1702 in the town of Mytny Stan, Tarussky district, Kaluga province, into the family of a small nobleman. Tatyana Fedorovna Kondyreva born in 1710 near the city of Aleksin of the same Kaluga governorate and also in a family of poor nobles. ...Actually, the Admiralty Board allowed officers to take their wives and children with them. And this step was completely justified in view of the obvious duration of the expedition. But the presence of women on the campaign was allowed only on the basis of long stops and inevitable wintering quarters. In the same detachment, an extraordinary, incredible event occurred: contrary to the well-known naval tradition, Lieutenant Pronchishchev interferes with his young wife in the execution of a matter of state importance. A woman on a warship is an unprecedented case! Pronchishchev did this without permission or with Bering’s unofficial consent, modern history does not know. But for a long time, in all subsequent historical and memoir references, she was mistakenly called Maria.

The voyage along the Lena passed safely and on August 2, 1735, the expedition reached the island of Stolb, from which the Lena delta begins. Initially, Pronchishchev planned to go through the Krestyatskaya channel, which led to the west, but the search for a fairway in it due to the decline in water was not crowned with success, so he decided to lead the double-boat along the Bykovskaya channel to the southeast. On August 7, the ship anchored at the mouth of this channel, waiting for favorable winds.

On August 14, 1735, Pronchishchev took the ship around the Lena delta. After quite a long time, “Yakutsk” rounded the Lena delta and headed along the coast to the west. Pronchishchev was the first to map the Lena delta. The delay in the Lena delta did not allow Pronchishchev to advance far during the first navigation. The short northern summer was ending, a rather strong leak developed on the ship and Pronchishchev decided to winter in places where fins were still found and the ship could be repaired. On August 25, the detachment stopped for the winter at the mouth of the Olenyok River (river) near the settlement of fur traders, having built two huts from driftwood. The winter passed safely, but scurvy began in the detachment.

The spring of 1736 in Ust-Olenyok turned out to be late and the sea cleared of ice only by August. Despite the difficulties that arose, in the summer of 1736 Pronchishchev continued along the coast to the west. On August 5, 1736, the detachment reached the mouth of the Anabara River. Surveyor Baskakov, going upstream of the river, discovered ore outcrops.

On August 17, 1736, off the eastern coast of Taimyr, the expedition discovered islands that they named in honor of St. Peter. Transfiguration Island was also discovered.

Moving further north in the following days along the edge of the continuous ice fast ice, which lies off the coast of the Taimyr Peninsula, the detachment passed several bays. The northernmost of the bays, Pronchishchev, was mistakenly mistaken for the mouth of the Taimyra River (in fact, it is Teresa Klavenes Bay). The coast was completely deserted, without the slightest sign of habitation. At latitude 77, the path to the wooden ship was finally blocked by heavy ice, and the frost began to draw in the free water. These days Chelyuskin wrote:

“At the beginning of this 9 o’clock calm, the sky is cloudy and gloomy, there is a great frost and there is slush on the sea, from which we are in great danger, that if it stays so quiet for one day, we are afraid of freezing here. We entered deep ice that on both sides and in front of us there were great standing smooth ices. They walked by rowing oars. However, God be merciful, God grant us a capable wind, then this sludge was blown away.”

Soon the travelers lost sight of the shore. Pronchishchev ordered to determine the position of the vessel using navigation instruments. "Yakutsk" ended up at 77° 29" N. This is the northernmost point reached by the ships of the Great Northern Expedition. Only 143 years later, Baron Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld on the ship "Vega" will advance in these places just a few minutes further north. The further path was closed. In the north and west there was continuous ice with rare polynyas and it was impossible to pass them on a double boat. "Yakutsk" turned back with the intention of wintering at the mouth of the Khatanga. Subsequently it was established that the expedition entered the Vilkitsky Strait and moved slightly to the north and reached a latitude of 77 degrees 50 minutes. Only poor visibility did not allow the expedition members to see the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago and the northernmost point of Taimyr and all of Eurasia - Cape Chelyuskin.

Pronchishchev refused to land in Khatanga Bay, having found no settlements there, and the ship headed to the former Olenyok winter quarters.

On August 29, Pronchishchev went on a reconnaissance boat and broke his leg. Returning to the ship, he lost consciousness and soon died. The true cause of death - fat embolism syndrome due to a fracture - became known only recently, after the traveler's grave was opened in 1999. Previously it was believed that Pronchishchev died of scurvy.

The Yakutsk made its further journey under the command of navigator Chelyuskin. A few days later he managed to reach the Ust-Olenyok winter quarters, where Pronchishcheva was interred, and Tatyana Pronchishcheva soon died.

On October 2, “Yakutsk” went into winter quarters, and Chelyuskin went with a report to Yakutsk by sleigh. He was appointed the new commander of the dubel-boat and the head of the Lena-Yenisei detachment. Khariton Prokopyevich Laptev.

Seeing the difficult situation of the expedition, Dmitry Yakovlevich Laptev, as the closest assistant to the absent Bering, decided to go for instructions and help to St. Petersburg, to the Admiralty College.

D. Ya. Laptev covered the long journey from Yakutsk to St. Petersburg on horseback. D. Ya. Laptev had enough time to think about the reasons for the failures of Lasinius, Pronchishchev and his own and outline a plan for future actions. D. Ya. Laptev arrived in St. Petersburg, firmly knowing what was needed for further work.

The Admiralty Board listened carefully to the messages of D. Ya. Laptev and, having discussed them, considered it necessary to continue the work. The board released additional funds and equipment and, at the suggestion of D. Ya. Laptev, instead of the deceased Pronchishchev, appointed commander of "Yakutsk" Khariton Prokopyevich Laptev.

Kh. P. Laptev previously served with his brother on Baltic ships, traveled to the Don, looking for places suitable for organizing a shipyard. Returning to the Baltic in 1737, Kh. P. Laptev was appointed captain of the yacht "Dekrone".

In March 1738, the Laptev brothers, having received the funds and equipment necessary to extend the work, left St. Petersburg for Yakutsk.

Upon arrival at the site, they inspected and repaired their ships, equipped them, and made careful plans for the expedition, designed to carry out work both from sea and from land.

On June 18, 1739, Dmitry Yakovlevich Laptev left Yakutsk on the Irkutsk with a crew of 35 people; On July 5, having passed the Lena delta, he was already at sea, heading east.

According to the adopted plan, D. Ya. Laptev sent a detachment under the command of senior sailor Loshkin, heading to the mouth of the Yana River by land, and a second detachment to the mouth of the Indigirka River under the command of surveyor Kindyakov. It was also planned to organize the work further - between Indigirka and Kolyma. On July 8, the Irkutsk reached the mouth of the Yana River and gradually moved further and further east, until ice conditions near the mouth of the Indigirka River forced it to winter.

The crew left the ship and spent the winter on the shore. Everyone continued to work. The wintering went well, and during this time the team did a great job of studying the territory. With the onset of spring, D. Ya. Laptev sent some of the people by land to Kolyma to carry out an inventory of the shores, and he himself and the rest of the team returned to the ship. The ship was trapped in ice. It was separated from clean water by an ice field about a kilometer long. D. Ya. Laptev took a difficult but true path. A channel was cut through the ice for a kilometer, through which the ship came out into clear water.

.png)

But the sailors' joy was short-lived. A storm broke out, again surrounding the ship with ice and throwing it aground. To refloat the ship, it was necessary to completely unload and disarm it, even the masts were removed. The sailors fought for the life of the ship and their own for two weeks. But finally, the Irkutsk was refloated and safely reached the mouth of the Kolyma; Having completed the necessary work here, D. Ya. Laptev moved further to the east.

Impassable ice was encountered at Cape Baranov. D. Ya. Laptev decided to return for the winter to Nizhnekolymsk on the Kolyma River. Wintering went well again. People continued to work.

In the summer of 1741, D. Ya. Laptev made another attempt to travel by sea east of Kolyma. Again, impassable ice was encountered at Cape Baranov, forcing the expedition to return to Nizhnekolymsk.

Having carefully processed the compiled inventories of the coast from the Lena to the Kolyma, D. Ya. Laptev went to the Anadyr prison on dogs and made a detailed inventory of the river. Anadyr and in the fall of 1742 returned to St. Petersburg.

Khariton Prokopyevich Laptev left Yakutsk at the end of July 1738, somewhat later than his brother. The Yakutsk crew, sailing with Lieutenant Pronchishchev, was taken by him almost unchanged. The navigator also set off on a new voyage Semyon Ivanovich Chelyuskin.

On August 17, Kh. P. Laptev reached the bay, to which he gave the name “Nordvik”. Having explored the bay, Kh. P. Laptev moved further to the west, visited Khatanga Bay and, leaving it, discovered Transfiguration Island. Then he headed north, following the eastern coast of the Taimyr Peninsula. At Cape Fadeya, ice blocked the way. Winter was approaching. Kh. P. Laptev returned back and spent the winter at the mouth of the Bludnaya River, in Khatanga Bay.

The team spent the winter safely in a house built from driftwood collected on the shore. Despite the winter conditions, work did not stop. At the same time, preparations were made for summer work from the sea and from the land.

At the wintering site, Kh. P. Laptev left large supplies of food and equipment. With the onset of spring, land survey work began. The boatswain Medvedev was sent to the mouth of the Pyasina River, and the surveyor Chekin with troops and food was sent to the mouth of the Taimyra River. These two detachments were unable to complete the work, but they found out the situation and gave Kh. P. Laptev the information necessary for the successful completion of work in the future. Kh. P. Laptev himself in August 1740, immediately after the ice broke up, made another attempt to bypass the Taimyr Peninsula by sea from the north. The attempt failed. The ship was trapped in ice and died. The crew and cargo were, by order of Kh. P. Laptev, transferred to the ice in advance.

.png)

The shore was 15 miles from the accident site. The team walked on foot, carrying loads, and moved towards the shore. But the closest accommodation was the expedition base at the mouth of the Bludnaya River. Kh. P. Laptev sent his detachment there. Four people could not bear the difficulties of the journey and died along the way. The rest made it to the base. Again a successful winter in the old place. The spring of 1741 came. Kh. P. Laptev, having lost his ship, decided to continue his research by land. He singled out three groups from his detachment. He sent one group under the command of navigator Semyon Chelyuskin to the mouth of the Pyasina River with the task of exploring the coast from the mouth of the Pyasina towards the mouth of the Taimyra.

The second group, under the command of surveyor Chekin, was supposed to examine the coast from the mouth of the Taimyra River. The third group was headed by Kh. P. Laptev himself. He had in mind to explore the interior regions of the eastern part of the Taimyr Peninsula and go to the mouth of the Taimyr River, where he was supposed to meet with the first two groups.

To ensure the normal operation of the groups, Kh. P. Laptev sent spare food and equipment ahead of each of them. Kh. P. Laptev sent all the people who were not included in the expedition groups and excess cargo on reindeer to Turukhansk.

Chekin soon returned to base, having not completed the task due to the difficulty of the journey and illness. Chelyuskin reached his destination and began work.

Kh. P. Laptev himself headed deep into the Taimyr Peninsula, went to Lake Taimyr, went down the Taimyr River to the sea and went to meet Chelyuskin.

Having finished their work, the travelers spent the winter in the city of Turukhansk on the Yenisei. In the spring of 1742, Semyon Chelyuskin returned to Taimyr to explore the remaining undescribed part of the peninsula and reached the extreme northern point of Asia - a rocky cape, which was later named after him. Cape Chelyuskin is located at 77°43" north latitude and 104°17" east longitude.

Having finished his work, Khariton Prokopievich Laptev returned from Turukhansk to St. Petersburg, where he continued to serve in the navy, holding command positions. He died on January 1, 1764.

More than two centuries separate us from the time when, overcoming constant difficulties and hardships, exposing themselves to all sorts of dangers, the Laptev brothers studied the distant and harsh sea and its coast.

They carried out their work on weak wooden ships, with primitive equipment and tools. They provided a variety of information about the nature of the region, its geography, coastline, sea depths, tides, population, magnetic declination, fauna, vegetation, etc. The thoroughness, accuracy and conscientiousness with which they carried out their work is amazing, how The strength of their will and love for their homeland is amazing, which allowed them to complete such a difficult task.

The sea whose shores they studied was named Laptev Sea.

KHARITON PROKOFIEVICH LAPTEV

The name of Khariton Laptev became widely known in Russia only a century after his feat.

Laptev has the honor of discovering the huge Taimyr Peninsula, stretching to the north between the Lena and Yenisei. Before Laptev appeared on these shores, the existence of Taimyr was not known in Russia.

Only Laptev was the first to establish the size and extent of this peninsula, described its relief and natural conditions, compiled the first navigational map of its shores and a unique geographical description of the nature of the interior regions and the peoples who inhabited them.

The work done by Laptev in the most difficult conditions of the wild nature of the North was so enormous that some even doubted the reality of his detachment reaching the northern point of Asia.

Khariton Prokofievich Laptev came from an old, albeit impoverished, family of Velikiye Luki nobles.

He was born in 1700 in the small village of Pekarevo, Slautsk camp, Velikiye Luki province. Here Khariton spent his childhood, receiving his primary education under the guidance of a local priest. In 1715, by decree of Peter I, among the noble minorities of the northern provinces, “as if living by water communications,” enrollment was carried out for the Maritime Academy, newly organized in the new Russian capital. Khariton Laptev went there with his younger brother Dmitry.

In 1718, the Laptev brothers, after passing their exams, were promoted to midshipmen and enlisted in the Baltic Fleet. Two years later, Khariton Laptev was promoted to the rank of non-commissioned navigator.

Five years later he was sent to Italy as part of a special naval mission, and upon his return Laptev was promoted to the first officer rank of midshipman.

In 1774, Khariton Laptev took part in the War of the Polish Succession, but there he was met with failure.

The frigate Mitau, on which Laptev served, was sent to Danzig with the task of finding out which countries' ships were supporting the contender for the Polish throne, Stanislav Leszczynski. However, the commander of the Kronstadt squadron, Admiral Gordon, who sent Laptev to conduct reconnaissance, did not write in the “warrant” given to the frigate commander that the French ships should be considered enemy. All this led to the fact that Mitau was surrounded by military ships of Stanislav Leszczynski's allies, and the entire crew of the frigate was captured.

Laptev also shared the fate of the Mitau crew. After the end of hostilities, prisoners were exchanged and the officers of the frigate were put on trial by military court on charges of surrendering the frigate to the enemy without a fight. According to Peter the Great's naval regulations, officers could lose their lives for such an offense. The verdict had already been passed, but there were witnesses who confirmed that the “warrant” did not consider the French ships to be enemy ships. A new investigation was ordered, and only in February 1736 the Mitau officers were released.

At first, Laptev sailed on the frigate Victoria in the Baltic Sea. Then he was sent to build warships in case of war with Turkey. After completing this task, Laptev returned to St. Petersburg, where he was assigned to command the court yacht Dekrone.

However, having learned that officers were needed for the Kamchatka expedition, Laptev in February 1737 submitted a petition addressed to Empress Anna Ioannovna with a request to send him to Siberia. For several months he waited for a response to his petition and only in December he was approved as commander of the double-boat “Yakutsk” of the Lena-Yenisei detachment with promotion to the next rank of lieutenant.

The instructions given to Laptev at the Admiralty Board instructed him to travel by sea from the Lena to the Yenisei and describe the unknown shores. Laptev was given a four-year period to complete the task. The Admiralty Board granted Laptev fairly broad powers to carry out the task, allowing him to resolve many issues at his own discretion.

In March 1738, Khariton and Dmitry Laptev left for Siberia.

On the way, they stopped in Kazan, where everything necessary for the expedition was located.

The Laptev convoy first walked along the Volga to the mouth of the Kama, then along the Kama and Chusovaya. The cargo was transported through the Urals by horse-drawn convoys to the Tura River. In Verkhoturye, all property was loaded onto small barges and boats, which moved along the Tura through Tyumen to the Tobol River.

From Tobolsk, barges with cargo traveled along the Irtysh to its confluence with the Ob, from where they went up the Ob to the Kebi River. From Kebi the barges went to the Makovsky fort, where all the property was loaded onto horses and transported to Yeniseisk.

By sledge, by the new year 1739, the Laptevs reached Ust-Kut on the Lena River, where planks and barges were already being built for floating equipment down the river.

On June 8, 1739, the Yakutsk moved downstream of the Lena. A large yalboat with firewood was in tow. A kayak with flour was towed behind the boardwalk.

The voyage along the Lena continued for more than a month, and finally, on July 21, 1737, the Yakutsk set out to sea heading west. Along the way, he often encountered ice floes, which the Yakutsk successfully avoided.

On July 27, high rocky headlands were discovered surrounding the entrance to the bay, which was not marked on the map. This was Cape Pax. Laptev gave this bay the name Nordvik (Northern Bay). Having completed the description of Nordvik, Laptev moved north. The further advancement of the Yakutsk was hampered by ice, which became more and more abundant.

Laptev intended to unload part of the provisions from the overloaded ship in the winter quarters of Konechny, located 12 km north of Cape Sibirsky, in case the Yakutsk died in the ice, and the crew would have to travel on foot. However, an east wind blew from the sea and ice appeared again, and Laptev ordered to go south, to the Khatoichsky Bay, where there was another winter quarters at the mouth of the Zhuravleva River. There was another winter quarters here, to which the boat was moved. Here the expedition members left the boat, and then the Yakutsk rushed with full sail along the eastern coast. Along the way he encountered almost no ice floes.

From the island of St. Paul (modern island of St. Andrew) "Yakutsk" walked along the coast to the west. However, he soon encountered ice floes again, which forced Laptev to swim near the shore. On the night of August 20, the south wind drove away the ice floes, and, using the resulting clearing, the Yakutsk crew first rowed and then sailed. Soon they entered Thaddeus Bay, which they mistakenly took for the mouth of the Taimyr River. It was never possible to find the mouth of the river, and Laptev designated the cape entering the sea as Cape Thaddeus.

It was impossible to go further beyond the cape to the north, and Laptev sent out small groups of people to scout out whether there was any passage in the ice floes. However, it soon became clear that ice floes covered all visible space in the north, and then Laptev decided to convene all the non-commissioned officers of his team for a council to decide on further actions. The council unanimously spoke in favor of returning to the south, where it was necessary to camp for the winter.

On August 22, the Yakutsk headed southeast. Under a favorable stormy northwest wind, the dubel-boat entered the Khatanga Bay by the morning of August 27.

Here Laptev intended to pick up the large yawlboat and provisions left from the winter quarters. However, the ice surrounded the coast so tightly that it was impossible to approach it.

It was decided to look for a new winter shelter for the ship and people. Such a place was found on the Khatanga Bay at the mouth of the Popichay River.

On August 28, the Yakutsk arrived at the winter hut, next to which by mid-September five residential buildings and barns were built, in which sails, cannons and provisions were stored. Laptev’s detachment was located in this village.

Provisions from the Ust-Olenek winter quarters were also transported here. In addition, fresh fish and reindeer meat were brought from the neighboring winter quarters.

Already in the winter hut, Laptev was thinking about continuing the work. The initial task at this stage was to determine from the sea the mouths of the Taimyra and Pyasina rivers. Already at the beginning of April, Laptev sent several people, led by surveyor N. Chekin, to inspect the coast of the mouth of the Taimyr and Pyasina rivers with a deck survey of the coast. However, the trip ended in failure, since Chekin had no experience in sleigh rides.

On June 15, Khatanga opened up and was soon freed from ice. On July 8, food and barrels of fresh water, which could be needed for sailing at sea, were loaded onto the Yakutsk.

On July 12, the Yakutsk left the coast and by the morning of the next day reached the last cape of the Khatanga River, called Korta. A large yawlboat was left here as unnecessary. However, it was still impossible to sail further - the bay was covered with unbroken ice. Only on July 30 did it become free of ice, and the Yakutsk set off, but two days later it found itself at an impassable wall of standing ice.

With great difficulty, Laptev and his comrades managed to find a channel and go to the mouth of the Zhuravleva River.

By the evening of August 12, the southeast wind dispersed the ice floes and the Yakutsk again began to make its way north. However, the voyage did not last long; the next day the Yakutsk was covered in ice. The dubel-boat was severely dented by ice floes, a leak appeared in it, no measures taken by the Yakutsk crew could save the vessel. Not only the Yakutsk, but the entire crew was in danger of death. However, standing ice was discovered to the west of the wreck site, which could have saved the ship's crew. With great difficulty, the boat filled with water was dragged along the standing ice, onto which they began to unload the cargo on board the Yakutsk.

By August 16, the crew of the ship went ashore, where they began to take everything removed from the ship. Here, on the steep rocky coast, Laptev ordered to dig round holes, line their bottom with driftwood, make ceilings from poles, covering them with brought sails taken from the Yakutsk. They had to spend time in these “earth yurts” until the ice became strong and it would be possible to cross it to the winter quarters.

On September 20, the ice became so strong that Laptev decided to send a group of nine soldiers led by Chekin to the southern shore of Maria Pronchishcheva Bay. They had to get to the nearest winter hut and ask for help there.

Laptev divided his entire detachment into three groups so that on the way they could stop in small fishing huts, changing each other. Laptev himself went with a second group of 15 people. A group led by navigator S. Chelyuskin was to follow him. Only sick soldiers and sailors, of whom there were four in total, were left in the yurt.

In five days, Laptev’s group covered 120 kilometers and finally arrived at Kozhin’s winter quarters.

On November 25, Laptev sent a report to the Admiralty Board, in which he outlined all the circumstances of the death of the Yakutsk and the council’s decision to conduct land surveys of the coast in the spring in groups of several people on dog sleds. The groups had to move towards each other from the mouths of the Khatanga, Nizhnyaya Taimyra and Pyasina rivers. It was decided to send soldiers and sailors who were not supposed to be involved in the filming to the Yenisei.

However, the first attempt to film the shores was unsuccessful for many of its participants, including Laptev himself; many fell ill with snow blindness - light burns of the eyes. Having barely recovered from his “personal illness,” Laptev rode west to meet Chelyuskin, who was moving from the east.

Along the way, Laptev discovered several small islands that were not marked on his map. On May 24, he crossed the strait, discerning an island visible in the north (now called Russian). At its southwestern tip, many hills were discovered, with no land between them. Laptev did not suspect that the hills were small islands, also already mapped.

From Russky Island, Laptev headed towards the western edge of the array of islands in the western part of the Nordenskiöld archipelago. Here he landed on a high island, later named after Makarov.

On May 28, Laptev and his companions set out south. However, on the way they were overtaken by a blizzard, visibility was lost, and instead of standing ice, the travelers almost hit the target that separated the hummocks from the standing ice.

On June 1, 1741, a meeting between Laptev’s group and Chelyuskin’s group took place near Cape Leman. Both groups traveled many kilometers towards each other along the northern coast from the mouths of the Pyasina and Taimyra rivers. “The weather is pretty bad,” Laptev wrote in his journal, describing this meeting. - Since noon, navigator Chelyuskin came to meet us, whose dogs that came with him were very thin, and a small number came with him. And, having fed the dogs, we set off to return the navigator.”

When the Pyasina River cleared of ice, Laptev swam up it, and then along its tributary, the Pure River, to the Yenisei. Laptev made the further journey across the tundra on reindeer, and the very next day he switched to a plank and went up the Yenisei, photographing the river banks along the way all the way to Turukhansk.

On August 29, Laptev and most of his detachment gathered in Mangazitsk (Turukhansk). During research in the spring of 1741, the Laptev expedition mapped a previously unknown sea coast between the mouth of the Nizhnyaya Taimyr and Yenisei rivers. However, it was still necessary to explore one route through the interior regions of Taimyr.

On February 8, 1742, Laptev, together with four sailors, left Turukhansk, and on March 2 arrived in Dudinka. Then Laptev rode on reindeer to the east of the Yenisei.

On March 19, he reached the mouth of the Norilskaya River and continued on his way to Lake Taimyr to meet Chelyuskin’s group. However, he soon realized that his further progress was difficult, since due to the early spring the snow had become soft. Having prepared a storehouse with provisions for Chelyuskin’s group, Laptev set off on the return journey.

At the sites, he gave orders to provide Chelyuskin’s team with deer or boats. On June 27, he reached the mouth of the Dudina River in the winter quarters of Bobylevo and, as soon as the Yenisei cleared of ice, on July 16, on a yasash plank, he arrived in Turukhansk, where four days later Chelyuskin arrived with his party.

In the fall of 1742, the entire Laptev detachment gathered in Yeniseisk. Laptev sent his report on the completion of the campaign to the Admiralty Board, accompanied by Chelyuskin.

In the winter of 1743, Laptev's detachment was disbanded. He himself was involved in drawing up two report maps and describing the territory he surveyed.

After hearing the report, the Admiralty Board decided to assign Laptev to the ship’s crew of the Baltic Fleet. He remained in his previous rank of lieutenant, without receiving any awards for his five years of work. Only seven years later, Laptev was awarded the rank of captain in connection with his appointment as assistant director of the newly opened Naval Cadet Corps.

During the Seven Years' War of 1757–1762, Laptev, with the rank of captain 2nd rank, commanded a warship blockading the Prussian coast. After the end of the war, he was appointed "Ober-Ster-Kriegskommissar" (chief quartermaster) of the Baltic Fleet.

But due to his failing health, Laptev retired to his Velikiye Luki village of Pekarevo, where he died on December 21, 1763.

The northwestern part of the coast of Taimyr, where in 1741 Laptev met Chelyuskin (the coast of Khariton Laptev), is named after Khariton Laptev. In 1878 A.E. Nordenskiöld named the southeastern tip of Taimyr Island Cape Laptev. In the Laptev Sea, on the northeastern coast of Taimyr, there is Cape Khariton Laptev.

In August 1980, on the high bank of the Khatanga River, at the site of the winter mooring of the double boat "Yakutsk", where the houses in which the expedition members lived were located, a monument to its participants was unveiled. The 5-meter-high monument is a metal cone-shaped cable sea buoy. This monument helps naval vessels navigate the fairway of the Khatanga River, emerging here from the Laptev Sea, along the path that Khariton Laptev’s detachment once laid here.

When passing by the monument, by order of the captain of the ship, a sound signal is given for a quarter of minutes, and in the ship's broadcast, the crew and everyone on board the ship is announced in whose honor this salute is being given.

From the book Power without Glory author Laptev IvanIvan Laptev Power without glory

From the book In the Name of the Motherland. Stories about Chelyabinsk residents - Heroes and twice Heroes of the Soviet Union author Ushakov Alexander ProkopyevichLAPTEV Grigory Mikhailovich Grigory Mikhailovich Laptev was born in 1915 in the village of Rudnichny, Satkinsky district, Chelyabinsk region, into a working-class family. Russian. In the village he graduated from school, and then from the Satka FZO school. Worked as a driller in a geological exploration party

From the book Personal Assistants to Managers author Babaev Maarif ArzullaKhariton Yuliy Borisovich Assistant to Kurchatov Igor Vasilyevich, one of the creators of nuclear physics in the USSR On February 27, 1904, Yuliy Borisovich Khariton was born in St. Petersburg. Future chief designer of nuclear weapons, three times Hero of Socialist Labor. For everyone

From the book Fatal Themis. The dramatic fates of famous Russian lawyers author Zvyagintsev Alexander GrigorievichDmitry Prokofievich Troshchinsky (1754–1829) “IT’S NOT ABOUT THE REPORT, BUT ABOUT THE SPEAKER” Unlike many other dignitaries, Dmitry Prokofievich managed not only to survive after the accession to the throne of Emperor Paul I, but also to rise to the occasion. D. P. Troshchinsky received new