Ancient civilizations of the Indus Valley city. Pre-Aryan Harappan civilization in India

At the beginning of the 20th century. In archaeological science, there is a strong opinion that the Middle East is the birthplace of the productive economy, urban culture, writing, and, in general, civilization. This area, according to the apt definition of the English archaeologist James Breasted, was called the “Fertile Crescent”. From here, cultural achievements spread throughout the Old World, to the west and east. However, new research has made serious adjustments to this theory.

The first finds of this kind were made already in the 20s. XX century. Indian archaeologists Sahni and Banerjee discovered civilization on the banks of the Indus, which existed simultaneously from the era of the first pharaohs and the era of the Sumerians in the III-II millennia BC. e. (three of the most ancient civilizations in the world). A vibrant culture with magnificent cities, developed crafts and trade, and unique art appeared before the eyes of scientists. First, archaeologists excavated the largest urban centers of this civilization - Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. By the name of the first she received name - Harappan civilization. Later, many other settlements were found. Now about a thousand of them are known. They covered the entire Indus Valley and its tributaries with a continuous network, like a necklace covering the northeastern coast of the Arabian Sea in the territory of present-day India and Pakistan.

The culture of ancient cities, large and small, turned out to be so vibrant and unique that researchers had no doubt: this country was not the outskirts of the Fertile Crescent of the world, but an independent center of civilization, today a forgotten world of cities. There is no mention of them in written sources, and only the earth retained traces their former greatness.

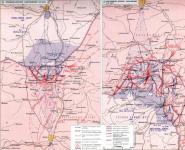

Map. Ancient India - Harappan civilization

History of ancient India - Proto-Indian culture of the Indus Valley

Other the mystery of ancient Indian civilization- its origin. Scientists continue to debate whether it had local roots or was introduced from outside, with whom intensive trade was carried out.

Most archaeologists believe that Proto-Indian civilization grew out of local early agricultural cultures that existed in the Indus Basin and the neighboring region of Northern Balochistan. Archaeological discoveries support their point of view. In the foothills closest to the Indus Valley, hundreds of settlements of ancient farmers dating back to the 6th-4th millennia BC have been discovered. e.

This transition zone between the mountains of Baluchistan and the Indo-Gangetic plain provided the early farmers with everything they needed. The climate was favorable for growing plants during the long, warm summers. Mountain streams provided water for irrigating crops and, if necessary, could be blocked by dams to retain fertile river silt and regulate field irrigation. The wild ancestors of wheat and barley grew here, and herds of wild buffalo and goats roamed. Flint deposits provided raw materials for making tools. The convenient location opened up opportunities for trade contacts with Central Asia and Iran in the west and the Indus Valley in the east. This area was more suitable than any other for the emergence of agriculture.

One of the first agricultural settlements known in the foothills of Balochistan was called Mergar. Archaeologists excavated a significant area here and identified seven horizons of the cultural layer in it. These horizons, from the lower, most ancient, to the upper, dating back to the 4th millennium BC. e., show the complex and gradual path of the emergence of agriculture.

In the earliest layers, the basis of the economy was hunting, with agriculture and cattle breeding playing a secondary role. Barley was grown. Of the domestic animals, only the sheep was domesticated. At that time, the residents of the settlement did not yet know how to make pottery. Over time, the size of the settlement increased - it stretched along the river, and the economy became more complex. Local residents built houses and granaries from mud bricks, grew barley and wheat, raised sheep and goats, made pottery and painted it beautifully, at first only in black, and later in different colors: white, red and black. The pots are decorated with whole processions of animals walking one after another: bulls, antelopes with branched horns, birds. Similar images have been preserved in Indian culture on stone seals. In the economy of farmers, hunting still played an important role, they did not know how to process metal and made their tools from stone. But gradually a stable economy was formed, developing on the same basis (primarily agriculture) as the civilization in the Indus Valley.

During the same period, stable trade ties with neighboring lands developed. This is indicated by the widespread decoration among farmers made from imported stones: lapis lazuli, carnelian, turquoise from Iran and Afghanistan.

Mergar society became highly organized. Public granaries appeared among the houses - rows of small rooms separated by partitions. Such warehouses acted as central distribution points for food. The development of society was also expressed in the increase in the wealth of the settlement. Archaeologists have discovered many burials. All residents were buried in rich outfits with jewelry from beads, bracelets, pendants.

Over time, agricultural tribes settled from mountainous areas to river valleys. They reclaimed the plain irrigated by the Indus and its tributaries. The fertile soil of the valley contributed to the rapid growth of population, the development of crafts, trade and agriculture. Villages grew into cities. The number of cultivated plants increased. The date palm appeared, in addition to barley and wheat, they began to sow rye, grow rice and cotton. Small canals began to be built to irrigate fields. They tamed a local species of cattle - the zebu bull. So it grew gradually the most ancient civilization of the north-west of Hindustan. At an early stage, scientists identify several zones within the range: eastern, northern, central, southern, western and southeastern. Each of them is characterized its own characteristics. But by the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. e. the differences have almost disappeared, and in its heyday The Harappan civilization entered as a culturally unified organism.

True, there are other facts. They bring doubts into the slender theory of the origin of the Harappan, Indian civilization. Biological studies have shown that the ancestor of the domestic Indus Valley sheep was a wild species that lived in the Middle East. Much in the culture of the early farmers of the Indus Valley brings it closer to the culture of Iran and Southern Turkmenistan. By language, scientists establish a connection between the population of Indian cities and the inhabitants of Elam, an area that lay east of Mesopotamia, on the coast of the Persian Gulf. Judging by the appearance of the ancient Indians, they are part of one large community that settled throughout the Middle East - from the Mediterranean Sea to Iran and India.

Adding up all these facts, some researchers have concluded that Indian (Harappan) civilization is a fusion of various local elements that arose under the influence of Western (Iranian) cultural traditions.

Decline of Indian civilization

The decline of the proto-Indian civilization also remains a mystery, awaiting a final solution in the future. The crisis did not start all at once, but spread throughout the country gradually. Most of all, as evidenced by archaeological data, the large centers of civilization located on the Indus suffered. In the capitals Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, it took place in the 18th-16th centuries. BC e. In all probability, decline Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro belong to the same period. Harappa lasted only slightly longer than Mohenjo-Daro. The crisis hit the northern regions faster; in the south, far from the centers of civilization, Harappan traditions persisted longer.

At that time, many buildings were abandoned, hastily made stalls were piled up along the roads, new small houses grew up on the ruins of public buildings, deprived of many of the benefits of a dying civilization. Other rooms were rebuilt. They used old bricks selected from destroyed houses. They did not produce new bricks. In cities there was no longer a clear division into residential and craft districts. There were pottery kilns on the main streets, which was not allowed in former times of exemplary order. The number of imported things decreased, which means that external relations weakened and trade declined. Craft production decreased, ceramics became coarser, without skillful painting, the number of seals decreased, and metal was used less frequently.

What appeared the reason for this decline? The most likely reasons seem to be of an environmental nature: a change in the level of the seabed, the Indus riverbed as a result of a tectonic shock that resulted in a flood; change in monsoon direction; epidemics of incurable and possibly previously unknown diseases; droughts due to excessive deforestation; soil salinization and the onset of desert as a consequence of large-scale irrigation...

The enemy invasion played a certain role in the decline and death of the cities of the Indus Valley. It was during that period that the Aryans, tribes of nomads from the Central Asian steppes, appeared in North-Eastern India. Perhaps their invasion was the last straw in the balance of the fate of the Harappan civilization. Due to internal turmoil, the cities were unable to withstand the onslaught of the enemy. Their inhabitants went to look for new, less depleted lands and safe places: to the south, to the sea, and to the east, to the Ganges valley. The remaining population returned to a simple rural lifestyle, as it had been a thousand years before these events. It adopted the Indo-European language and many elements of the culture of the nomadic aliens.

What did people look like in ancient India?

What kind of people settled in the Indus Valley? What did the builders of magnificent cities, the inhabitants of ancient India, look like? These questions are answered by two types of direct evidence: paleoanthropological materials from Harappan burial grounds and images of ancient Indians - clay and stone sculptures that archaeologists find in cities and small villages. So far these are few burials of residents of proto-Indian cities. Therefore, it is not surprising that conclusions regarding the appearance of the ancient Indians often changed. At first, it was assumed that the population would be racially diverse. The city organizers showed features of the proto-Australoid, Mongoloid, and Caucasian races. Later, the opinion was established about the predominance of Caucasian features in the racial types of the local population. The inhabitants of proto-Indian cities belonged to the Mediterranean branch of the large Caucasoid race, i.e. were mostly human dark-haired, dark-eyed, dark-skinned, with straight or wavy hair, long-headed. This is how they are depicted in sculptures. Particularly famous was the carved stone figurine of a man wearing clothes richly decorated with a pattern of shamrocks. The face of the sculptural portrait is made with special care. Hair grabbed with a strap, a thick beard, regular features, half-closed eyes give a realistic portrait of a city dweller,

Indus Valley

The earliest known crops of south Asia came down from the hills of Balukistan, Pakistan. These semi-nomadic people raised wheat, barley, sheep, goats and cattle. Pottery began to be used starting from the sixth millennium BC. The oldest grain storage structure in this region was found at Mehrgara in the Indus Valley. It dates back to 6,000 BC.

The settlements consisted of houses built from mud, divided by partitions into four internal rooms. Objects such as baskets, bone and stone tools, beads, bracelets, and pendants were found in the burials. Traces of animal sacrifices were occasionally found.

Figurines and designs on sea shells, limestone, turquoise, lapis lazuli, sandstone and polished copper were also found in the ancient settlements of the Indus Valley. By the fourth millennium BC. technological inventions included stone and copper drills, updraft furnaces with large recesses, and copper melting crucibles. Geometric patterns appear on buttons and decorations.

By 4000 B.C. The pre-Harappan culture, with fairly powerful trading networks at that time, separated from the overall picture. Indian civilization was divided between two powerful cities: Harappa and Mogenjo-daro. In addition to them, it included more than a hundred towns and villages of relatively small size.

In size, these two cities reached about a square mile, and were centers of political power. Sometimes the entire Indian civilization is presented either as a combination of two powers, or as one large empire with two alternative capitals. Other scholars say that Harappa became the successor of Mogenjo-daro, which was destroyed by very strong floods. The southern region of civilization at Kithyavara and beyond appeared later than most Indian cities.

There, villagers also grew crops including peas, sesame seeds, beans and cotton. The Indus Valley civilization is also known for its use of decimals in the system of weights and measures, as well as the first attempts to create dental offices. Waterways played a huge role in the trading activities of civilization, as well as the introduction into use of carts harnessed to oxen.

Among the major cities of the civilization were Lothal (2400 BC), Harappa (3300 BC), Mogenjo-daro (2500 BC), Rakhigarhi and Dholavira. The streets were laid out on a grid system, and a sewerage and water supply system was developed. The Indus Valley Civilization declined by 1700 BC. Among the reasons for its destruction are both external invasions and the drainage of rivers flowing from the Himalayas to the Arabian Sea, as well as geographical and climatic changes in the valley, which is why the Thar Desert arose.

The origins of the conquerors are a source of controversy. The period of decline of Indian civilization coincides in time and place with the early Aryan raids on the Indian region, as described in such ancient books as the Rig Veda, which describes aliens attacking "walled cities" or "citadels" of local inhabitants, and the Aryan god of war Indra – destroying cities like time destroys clothes. As a result, the cities were overthrown and the population decreased significantly. After this, people decided to migrate to the more fertile valley of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers.

The legacy of the Indus Valley civilization lies not only in the invention of new technologies and the development of old ones, but also in the enormous influence on the formation of religious cults that later arose in this territory.

The name of the Indus River served as the basis for the name of the country - “India”, which in ancient times meant the space east of the Indus, where the states of Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh are currently located. Until relatively recently (several more than a hundred years ago), the Aryan aliens were considered the first creators of civilization on the Indian subcontinent. The generally accepted opinion was that no information about the great previous culture was preserved in written texts. Now we can say that they are still recognized, although with difficulty. In particular, Strabo’s “Geography”, with reference to the Greek Aristobulus, speaks of a vast country abandoned by its inhabitants due to a change in the course of the Indus. Such information is rare, and sources characterizing the Harappan culture, or the Indus Valley civilization, were obtained and continue to be obtained during archaeological excavations.

History of the study

Alexander Cunningham. 1814-1893 The first head of the Indian Archaeological Survey.

The Harappan civilization, unlike most other ancient civilizations, began to be studied relatively recently. Its first signs were discovered in the 60s of the 19th century, when samples of stamp seals so characteristic of this civilization were found near Harappa in Punjab. They were discovered during the construction of road embankments, for which purpose huge masses of the ancient cultural layer were used. The seal was noticed by engineer officer A. Cunningham, later the first head of the Archaeological Survey of India. He is considered one of the founders of Indian archaeology.

However, only in 1921, an employee of the Archaeological Service R.D. Banerjee, while exploring the Buddhist monument at Mohenjo-Daro (“Hill of the Dead”), discovered here traces of a much more ancient culture, which he identified as pre-Aryan. At the same time, R.B. Sahni began excavations at Harappa. Soon, the head of the Archaeological Service, J. Marshall, began systematic excavations in Mohenjo-Daro, the results of which made the same stunning impression as the excavations of G. Schliemann in Troy and mainland Greece: already in the first years, monumental structures made of baked bricks and works of art were found ( including the famous sculpture of the “priest king”). The relative age of the civilization, traces of which began to be found in various regions of the north of the peninsula, was determined thanks to the finds of characteristic seals in the cities of Mesopotamia, first in Kish and Lagash, then in others. In the early 30s of the XX century. The date of the civilization, the existence of which was not recognized in the ancient written texts of its neighbors, was determined as 2500-1800. BC. It is noteworthy that, despite new dating methods, including radiocarbon dating, the dating of the Harappan civilization during its heyday is not much different now from that proposed more than 70 years ago, although calibrated dates suggest its greater antiquity.

Lively debate was caused by the problem of the origin of this civilization, which, as it soon became clear, spread over a vast territory. Based on the information that existed at that time, it was natural to assume that the impulses or direct influences that contributed to its emergence came from the west, from the region of Iran and Mesopotamia. In this regard, special attention was paid to the Indo-Iranian border region - Balochistan. The first finds were made here back in the 20s of the 20th century. M.A. Stein, but large-scale research was undertaken after the Second World War and the acquisition of independence by the states of the subcontinent.

Before the emergence of independent states, archaeological research on Harappan culture was limited mainly to the central region of the “Great Indus Valley” (a term coined by M.R. Mughal), where the largest cities, Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, are located. Then in India, intensive research was carried out in Gujarat (large excavations - Lothal and Surkotada), Rajasthan (excavations of Kalibangan are especially important here), and Punjab. Large-scale work in the second half of the 20th century. were carried out where the river used to flow. Hakra-Ghaggar. About 400 settlements with strata from pre-Harappan to post-Harappan cultures were discovered here.

In the 50-60s, data was obtained on Eneolithic (Chalcolithic) cultures, the ceramics of which were similar to finds known in Iran, Afghanistan, and southern Turkmenistan. Assumptions about the influence from these regions, which caused the emergence of first the pre-Harappan cultures, and then Harappa itself, were later corrected. What seemed to be evidence of migrations began to be perceived as the result of interactions, influences that turned out to be beneficial, since the local population had the ability not only to perceive them, but also to transform them, based on their own traditions. A special role in understanding the processes of the emergence of the Indus Valley civilization was played by excavations in Pakistan, in particular the Neolithic - Bronze Age settlements of Mehrgarh on the river. Bolan, conducted by French researchers.

For the preservation and future research of the monuments of the Harappan civilization, the efforts undertaken by UNESCO in the 60s of the 20th century are important. attempts to save one of the most important cities - Mohenjo-Daro - from soil water and salinization. As a result, new data were obtained that clarified and supplemented those already known.

Territory and natural conditions of the Indus Valley

The Indus Valley lies in the northwestern corner of the vast subcontinent, most of which is currently located in Pakistan. It is part of a zone of cultural integration, bounded on the north by the Amu Darya, on the south by Oman, extending 2000 km north of the Tropic of Cancer. The climate throughout the zone is continental, the rivers have internal drainage.

From the north, the subcontinent is bounded by the highest mountain system of the Himalayas and Karakoram, from where the largest rivers of the peninsula originate. The Himalayas play an important role in meeting the summer monsoon, redistributing its course, and condensing excess moisture in glaciers. It is important that the mountains are rich in wood, including valuable species. From the southwest and southeast the peninsula is washed by the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. The Indo-Gangetic Plain forms a crescent 250-350 km wide, its length from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal is 3000 km. Five tributaries of the Indus irrigate the plain of the Punjab-Five Rivers - these are Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej. The western part of the Ganges valley and the area between the Ganges and the Jamna (Doab) is the place of formation of the classical culture of India, Aryavarta (Country of the Aryans). In the Karachi region, Indus deposits form a shelf 200 km long. Now the Indus Valley is a bare lowland with dry river beds and sand dunes, although even under the Mughals it was covered with dense forests teeming with game.

To the south of the plain lie the highlands and Vindhya mountains, to the south is the arid Deccan plateau, framed on the west and east by the mountain ranges - the Western and Eastern Ghats. Most of the rivers of the plateau flow from west to east, with the exception of only two significant ones - the Narmada and the Tapti. The geographical continuation of the peninsula is the island of Ceylon. The coastal part is narrow, with few good ports. The total length of the subcontinent from Kashmir to Cape Comorin is about 3200 km.

In the northwest, a significant part of Pakistan is occupied by the mountains and valleys of Baluchistan. This is an area that played an important role in the formation of the Indus Valley Civilization.

The sources of minerals used in ancient times were located both outside (which will be discussed specifically below) the subcontinent and on it itself. Copper probably came, in particular, from deposits between Kabul and Kurrat, from Balochistan and Rajasthan (Ganesh-var-Khetri deposit). One of the sources of tin could have been deposits in Bengal; it is possible that it also came from Afghanistan. Gold and silver could come from Afghanistan and the south of the Deccan. Semi-precious and ornamental minerals were delivered from Khorasan (turquoise), from the Pamirs, from Eastern Turkestan, from Tibet, from Northern Burma (lapis lazuli, jade). Deposits of ornamental stones, from which people loved to make beads, were located on the subcontinent.

The climate, generally tropical monsoon, is at the same time diverse. In the Indo-Iranian border region it is semi-arid with predominantly summer precipitation. East Sindh receives 7 mm of rainfall annually. In the north, in the Himalayas, winters are cold, on the plains they are mild, and summers are hot, temperatures up to +43°C. On the Deccan Plateau, temperature fluctuations between seasons are less dramatic.

The geographical location of the Indian subcontinent determines the specifics of its climate, and therefore the characteristics of the economy. From October to May, rain is rare, with the exception of areas of the west coast and certain areas of Ceylon. The peak of heat occurs in April, by the end of which the grass burns out and leaves fall from the trees. In June, the monsoon season begins, lasting about two months. At this time, activities outside homes are difficult, nevertheless, it is perceived by Indians as Europeans perceive spring, a time of revitalization of nature. Now, as partly in ancient times, two types of crops are practiced - rabi, using artificial irrigation, in which the crop was harvested in early summer, and kharif, in which the crop was harvested in the fall. Previously, soil fertility was regularly restored by the floods of the Indus, and farming conditions were favorable for agriculture, livestock breeding, fishing, and hunting.

The nature of the subcontinent is characterized by its peculiar severity - people suffered and continue to suffer from heat and floods, epidemic diseases characteristic of a hot and humid climate. At the same time, nature served as a powerful stimulus for the formation of a vibrant and original culture.

Characteristics of the Harappan civilization

Chronology and cultural communities

The chronology of the Harappan civilization is based on evidence of its contacts mainly with Mesopotamia and radiocarbon dates. Its existence is divided into three stages:

- 2900-2200 BC. - early

- 2200-1800 BC. - developed (mature)

- 1800-1300 BC. - late

Calibrated dates date its beginnings back to 3200 BC. A number of researchers note that calibrated dates conflict with Mesopotamian dating. Some researchers (in particular, K.N. Dikshit) believe that the late period of the Harappan civilization lasted until 800 BC, i.e. the time of iron's appearance here. Nowadays it can be considered a generally accepted opinion that the end of the existence of civilization was not immediate and in some areas it existed until the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. and further.

"Dancing Girl" Found in 1926 in Mohejo-Daro. Copper, height 14 cm. Approx. 2500-1600 BC.

For a long time, there was an idea in science of the Harappan civilization as something uniform and little changing over the centuries. This idea is the result of a lack of information and underestimation by archaeologists at a certain stage of research of facts indicating the peculiarities of the relationship between human economic activity and the natural environment, the characteristics of economic activity and culture in the broadest sense of the word. In recent decades, archaeologists have identified several zones characterized by specific features of material culture -

- eastern,

- northern,

- central,

- southern,

- western,

- southeast.

Nevertheless, the proximity of the material elements of civilization, at least during its heyday, presupposes the existence of a culture whose bearers in different areas maintained close contacts with each other. How were their communities organized? Why did such a large community develop at all? Why is it believed (although new evidence may refute this) that large cities emerge relatively quickly? What role did trade play in civilization? Judging by how ideas about this culture are changing under the influence of new discoveries, its image is still very far from clear.

Geography of areas of cultural distribution and their features

The main areas of distribution of the Harappan civilization are the Indus Valley in Sindh with the adjacent lowlands, the middle reaches of the Indus, Punjab and adjacent areas, Gujarat, Balochistan. At the peak of its development, Harappa occupied an unusually vast territory for an early civilization - about 800,000 square meters. km, significantly exceeding the territory of the early states of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Probably, not all territories were inhabited at the same time and developed with the same intensity. It can be assumed that the development of the Indus Valley also took place from the territory of Baluchistan; it was the inhabitants of this region that could lay the foundations of the Harappan civilization. At the same time, more and more materials are appearing indicating the existence of pre-Harappan inhabitants in the Indus Valley. Gujarat acquires importance only at a later stage, at the same time Makran is being developed (its coast is convenient for navigation), signs of the Harappan civilization indicate the gradual spread of its carriers to the south (in particular, in Kutch, Harappan ceramics appear along with local pottery) and the east. Climatically, these zones differ:

- The plains of Pakistan experience the effects of the summer monsoons.

- The climate on the Makran coast is Mediterranean.

- In Baluchistan, small oases are located in river valleys with permanent or seasonal watercourses, and pastures are located on mountain slopes.

- In some areas (Quetta Valley), where rainfall is relatively high (more than 250 mm per year), rain-fed farming is possible on a limited scale. In this area there are deposits of various minerals, copper; Lapis lazuli was recently discovered in the Chagai Mountains, but the question of the use of this deposit in ancient times still remains open.

Balochistan is important as a relatively well-studied region, where settlement dynamics can be traced back to the Neolithic era (Mehrgarh). At the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. the population in the north and central part becomes rare and only in the south does the Kulli culture continue to exist. It is possible that the reason is the disruption of old economic ties between the population of mountainous zones and valleys. At the same time, the population of the Indus Valley increases, although the relative desolation of Balochistan does not mean that only from this region there was an influx of population; moreover, it is very likely that for various and as yet unclear reasons, people from other neighboring regions came to the area of the Harappan civilization. It is noteworthy that Harappan settlements were also located on the edge of the Indus Valley, on the routes leading to Iran and Afghanistan.

The emergence of such a vast civilization is the result of economic and cultural integration, in which regional characteristics were preserved. Continuity of development with neighboring areas and with the pre-Harappan cultures of the Indus Valley can be traced in many ways. In the end, a completely unique culture was formed. Its most important features are

- extensive development of large river valleys,

- the emergence of large cities (evidence of the existence of a complexly structured society or societies),

- exchange over long distances,

- development of crafts and highly artistic arts,

- the emergence of writing,

- the existence of complex religious ideas, calendar, etc.

It is hardly productive to believe that the “idea of civilization” was brought to the Indus Valley from outside, from Mesopotamia or Iran. On the contrary, all available evidence points to its deep local roots, although one cannot ignore the role of contacts with other cultural formations, the extent of the expected impact of which, however, remains unclear. Thus, A. Dani believed that in neighboring Iran three regions played an extremely important role in the formation of Harappa - the southeast (Bampur, Tepe Yahya and the coast), the Helmand region, an intermediary in the transfer of northern and southeastern Iranian cultural elements, and the Damgana region in the northeast. From there, connections spread through Afghanistan and Balochistan. Further we will have to say what role distant connections played in the history of Harappa.

The central part of the Harappan civilization was located in the Indus Valley, a huge river with a variable course, the depth and width of which doubled in summer as a result of melting snow and monsoon rainfall. Its waters bring fertile deposits, but the instability of the river has created and continues to create great difficulties for the development of land. In Sindh, where one of the largest cities of the Harappan civilization, Mohenjo-Daro, is located, the coastal areas were dominated by lush thickets of reeds and moisture-loving plants, then there were forests in which reptiles, rhinoceroses and elephants, tigers, wild boars, antelopes, and deer lived in ancient times. Until relatively recently, as mentioned above, these places abounded in game. The bearers of the Harappan culture depicted many representatives of the local fauna and flora on their products.

Another important territory of civilization was the Punjab, where the city that gave its name to the entire culture is located - Harappa. The natural situation here is close to that in Sindh; the flora and fauna differ little from those in Sind. Rain-fed farming is possible in the Islamabad area. Forests are common in the hills and mountains surrounding Punjab and surrounding areas. There is reason to believe that mobile forms of pastoralism played a significant role in ancient times in Punjab, especially in neighboring Rajasthan.

The geographical conditions of Gujarat are similar to those characteristic of Southern Sindh. Recently, signs of the existence of pre-Harappan settlements have been discovered here.

Population of the regions

Anthropological data, according to some researchers, indicate the heterogeneity of the anthropological type of the bearers of the Harappan civilization. Among them were representatives of the Mediterranean and Alpine types, according to some researchers, originating from the west, Mongoloids from mountainous regions and proto-Australoids, a supposed autochthonous population. At the same time, V.P. Alekseev believed that the main type was long-headed, narrow-faced Caucasians, dark-haired and dark-eyed, related to the population of the Mediterranean, the Caucasus, and Western Asia. It is possible that the diversity of funeral rites of Harappa itself, Mohenjo-Daro, Kalibangan, Rupar, Lothal, and Balochistan speaks about the multi-ethnicity of the bearers of the Harappan culture. The appearance of corpses in urns (simultaneous with burials in Swat) in late Harappa is noteworthy.

Economy in the Harappan civilization

Due to the diversity of environmental conditions, the economy was dominated by two forms - agriculture and livestock raising and mobile cattle breeding; gathering and hunting, and the use of river and sea resources also played a role. According to B. Subbarao, in the early history of India three stages can be distinguished, with which the prevailing forms of economic management are associated -

- pre-Harappan - in the north-west there were cultures of settled farmers and pastoralists, in the rest of the territory - hunters and gatherers.

- Harappan - there was an urban civilization, communities of archaic farmers-pastoralists and hunter-gatherers.

- and post-Harappan - settled agricultural cultures spread widely, the area of which included Central Hindustan, which felt the strong influence of the Harappan civilization.

Rain farming was practiced on lands that were sufficiently moistened by monsoon rains. In the foothills and mountain areas, stone embankments were built to retain water, and terraces were built to arrange crop areas. In river valleys in ancient times, although there is no definitive data on this, flood waters were accumulated by creating dams and dams. There is no information about the construction of canals, which is understandable due to thick layers of sediment. The main agricultural crops were wheat and barley, lentils and several types of peas, flax, as well as such an important crop as cotton. The main harvest is believed to be until the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. collected in summer (rabi). Later, in some areas, the kharif crop was also practiced, in which sowing was done in summer and harvesting in autumn. During this late period, millet introduced from the west and its varieties spread. They begin to cultivate rice - imprints have been found in Rangpur and Lothal; its cultivation is possible in Kalibangan. In western Uttar Pradesh, intermediate forms from wild to cultivated have been identified. An opinion was expressed about the beginning of rice cultivation here in the 5th millennium BC, somewhat earlier than in China. It is believed that at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. This important crop is becoming increasingly widespread in South Asia, although its origins remain unclear.

New forms of agriculture made it possible to move away from the characteristic Harappan practice of growing winter cereals, thanks to which new zones were introduced in the old territories, and lands in the east were also developed. By the end of the 4th - beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. the livelihood base becomes more diverse than before. The resources of sea coasts and rivers are being exploited more widely; in some settlements, fish and shellfish were used more than other animal foods (for example, Balakot).

As already mentioned, the Neolithic inhabitants of the territories that were later covered by the Harappan civilization were engaged in animal husbandry. Different types of livestock predominated in different places; large cattle dominated on well-watered alluvial lands, although small ones were also bred. Outside the alluvium the picture was reversed. In the alluvial valleys, primarily in the Indus Valley, the number of cattle was very significant - in some places up to 75% of all animals used (Jalipur near Harappa).

Important changes occur at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC: in the settlement of Pirak in the northern part of the Kachi Valley, near Mehrgarh, not only the bones of a camel and a donkey were discovered, but also the oldest evidence of horse breeding in South Asia.

To cultivate the land, a primitive wooden plow was used, to which oxen were harnessed, but it is obvious that small areas of particularly soft soil were cultivated with a hoe, a tool such as a digging stick and a harrow. In Kalibangan, traces of cross-plowing were discovered - further evidence of highly developed agriculture. The use of crop rotation is possible. It is obvious that there are different ways of managing; there is reason to believe that they played a complementary role. At the same time, there is no data on how relations between, for example, mainly fishermen and farmers or livestock breeders were regulated.

Settlements of the Harappan civilization

Studying the dynamics of the spread of the Harappan culture is difficult due to the low availability of early strata. Systems of interconnected settlements of different sizes and functions are also difficult to identify due to the concealment of many settlements, primarily small ones, under layers of sediment. Despite the difficulties of studying settlement dynamics, some progress has been achieved in this area. Thus, it is believed that more than a third of the settlements of the Amri culture in Sindh were abandoned during the Harappan time, but the rest continued to exist in the southwestern part.

Most settlements are small, from 0.5 to several hectares, these are rural settlements. The population was mainly rural. Currently, more than 1000 settlements have been discovered. There are four known large settlements (besides the two long-known ones, Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, Ganveriwala and Rakhi-garhi in Punjab), the area of which amounts to many tens of hectares, although the exact inhabited territory can be difficult to determine. Thus, Hill DK, excavated in Mohenjo-Daro, has an area of 26 hectares, while the total area is determined to be 80 and even 260 hectares, Hill E in Harappa is 15 hectares, although there are other hills here.

For a number of large settlements, a three-part structure was revealed - the parts received the conventional names “citadel”, “middle city” and “lower city”. A fourth development area has also been discovered in Dholavira. Both large and some relatively small settlements had perimeter walls surrounding a sub-rectangular area. They were built from baked bricks and adobe (in Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and some other settlements), stone and other available materials. It is assumed that the main purpose of the bypass walls was not defensive; they were supposed to serve as a means of protection against floods. Perhaps their construction was a consequence of the desire to limit the habitat of certain social organisms. Thus, in Banawali, Surkotada and Kalibangan, the territory was divided into two parts by a wall. There is an opinion that fortification itself was necessary only on the outskirts of Harappan territory, at outposts created on foreign lands. The regular development of Harappan settlements sharply distinguishes them from the chaotic layout of cities of other civilizations of the Ancient East and can contribute to the reconstruction of the features of social organization, which is still far from clear.

In conditions favorable for study, it is possible to establish that the settlements were located in groups - “clusters”. The paucity of settlements in the vicinity of Harappa is surprising. A cluster of settlements was discovered 200 km south of Harappa, near Fort Abbas. The early Harappan settlement of Gomanwala had an area of 27.3 hectares, perhaps almost the same as contemporary Harappa. Another cluster was discovered upstream of the Ghaggar in Rajasthan - these are Kalibangan, Siswal, Banavali, etc.; Pre-Harappan layers were also exposed here (the Sothi-Kalibangan complex, which is similar to Kot Diji). With the beginning of Harappa, significant changes occurred in the Hakra-Ghaggar system: the number of settlements quadrupled and reached 174. In the cluster at Fort Derawar, the largest was Ganveriwala (81.5 hectares), located 300 km from Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa.

320 km from Harappa, on Drshadvati, there is a settlement called Rakhigarhi, the area of which is supposed to be 80 hectares, although it has not been excavated. In Gujarat, Harappan settlements are small. In late Harappa there were more than 150 settlements here, many of them small and seasonal. The coastal Lothal stands out - a supposed port that carried out trade in copper, carnelian, steatite, shells, maintaining connections with hunting-gathering communities and, perhaps, those who were engaged in specialized cattle breeding.

Recently, it has been suggested that on the territory of the Harappan civilization from the period preceding it to the later period, there were 7 or 8 large settlements - “capitals”, surrounded by towns and villages. In the strict sense, these were not central settlements, since they could also be located in peripheral territories, establishing contacts between zones that were different in ecological and economic terms.

Settlement of Mohenjo-daro

It is advisable to consider the features of large settlements using the example of the long-studied Mohenjo-Daro. Its exact dimensions are unknown due to accumulated sediments, but it is significant that traces of buildings were found 2 km from the supposed city border. During the heyday, the maximum number of inhabitants is determined to be 35-40 thousand people. The thickness of the cultural layer is very significant; fragments of clay vessels were found at a depth of 16 to 20 m from the level of the modern surface, while the mainland was not reached. And now the ancient division of the city into two parts is clearly visible - the “citadel” and the “lower city”, separated by an undeveloped area. The building materials were burnt and mud brick and wood. In all likelihood, baked brick was used because of its ability to resist the destructive effects of moisture.

The “citadel” structures were located on a five-meter brick platform. Two large structures of unclear purpose were excavated here, which were most likely intended for meetings (the assumption that one of them could have been the residence of a high-ranking official is unlikely). One of them, with an area of 70x22 m. with thick walls, had a vestibule, the other had a hall with an area of about 900 sq. m. m. - was divided into four parts by rows of pillars.

The foundation of the structure, the upper part of which was wooden, was also discovered here. According to popular belief, it was extensive, with an area of 1350 square meters. m., a public granary, at the base of which there are deep ventilation channels. A similar granary was discovered in Harappa at the foot of the “citadel”; here its area is 800 sq. m.

Finally, on the “citadel” there was a “large pool”, built later than other buildings. Its area is 11.70 × 6.90 m, depth - 2.40 m. Wooden stairs coated with bitumen led to it from the narrow sides. For waterproofing, lime and bitumen coating was made. The pool was filled from a nearby well and emptied using a chute in one of the walls. It was surrounded by a gallery, from which the pillars have been preserved. It is believed that it could have served for ritual ablutions, to which great importance was attached. Evidence of this is the existence of “bathrooms” in residential buildings.

“Lower Town” was occupied by residential development. The blocks of houses were separated by straight streets and alleys located at right angles. The significant height of the walls - up to 6 m - gave rise to the now rejected opinion that the houses were not one-story: the height of the walls, as well as the great depth of the regularly located wells (one for every three houses), are the result of reconstruction.

Premises with flat ceilings were grouped around courtyards; the area of the largest block, which consisted of two parts connected by a covered passage, was 1400 sq.m.; there is no basis to judge that it belongs to a high-ranking official. In general, the area of the houses reached 355 square meters. m, and they consisted of 5-9 rooms.

Landscaping was unusually developed for antiquity. Bathrooms and toilets are found in the houses. Under the pavements there were sewer channels lined with baked bricks, and settling tanks were located at a certain distance from each other.

Relatively recent further investigations of Mohenjo-Daro have made it possible to trace changes in the principles of its development. During the developed Harappan period, it was cramped, with wide axial streets. The houses were both small and large, their plans varied. No traces of craft activity were found. Later, the number of small buildings increases, and the layout becomes more unified. The craft zone is approaching the residential zone. Finally, at the late stage of civilization, dwellings form isolated groups, and traces of handicraft production are discovered. The sewer system is falling into disrepair, which indicates a crisis in the organization of urban life.

Crafts and art

For the traditional culture of antiquity, which includes the Harappan culture, the division into craft and art is hardly legitimate. The creations of artisans, whether they were intended for everyday life or for rituals, are often marked by high skill. At the same time, among the things of each category there are better and worse made ones, and there are also rough ones, the manufacture of which did not require great skill. Differences in the quality of products indicate the existence of high-class professionals, stone carvers, jewelers, and sculptors. In different settlements, workshops were discovered where they made dishes, jewelry (including from shells), etc. The works of Harappan craftsmen are distinguished by their deep originality, and attempts to find analogies for them in other regions, in particular in Mesopotamia, as a rule, come down to a small number of probable imports from the Indus Valley and difficult to prove similarities of individual pictorial motifs.

Tools

So, the production of tools, utensils, and building materials was highly developed and specialized. One of the important indicators is the level of metalworking. The paucity of weapons is noteworthy, although copper and bronze daggers and knives, arrowheads and spearheads were found. Labor tools are largely associated with wood processing (axes, chisels, adzes) and with household chores (needles, piercing tools). Vessels were made from copper and silver, and rarely lead. Casting in open molds, cold and hot forging were known; Some items were cast using the lost wax technique. Alloys of copper with arsenic, lead and tin were used, and a large percentage - about 30 - of tin bronzes is noteworthy. Jewelry (bracelets and beads) was made from stone, shells, copper, silver, and rarely gold. Bracelets, as in later times, were worn a lot; in all likelihood, this custom was of a ritual nature. In special cases, vessels made of copper and even gold were used.

Stone tools have not gone out of use either, and over time the variety of types decreases, the quality of raw materials and processing technology increases. Vessels were made from soft varieties of stone, including shaped ones, which had a ritual purpose, and from various minerals - beads, seals. Materials for both metal and stone products were often delivered from afar.

Ceramics

Another indicator of a highly developed craft is ceramic production. The dishes were made on a rapid rotation wheel and fired in two-tier furnaces. The shapes are varied and generally standard - bowls, goblets, dishes, braziers, vessels with a pointed bottom and stands, vessels for making dairy products. The tradition of painting vessels is preserved, although it is dying out: black painting on a red background, geometric and figurative - images of animals, plants, fish. Although the pottery is of good quality, the vessels are heavy and differ from the more elegant products of pre-Harappan times, which happens in the ceramic production of not only ancient cultures when it becomes widespread.

Women's figurines were sculpted from clay, and less often, men's figurines, including characters in horned headdresses. They are undoubtedly associated with mythological ideas and rituals. These figurines are quite conventional, with molded details depicting body parts and numerous decorations. Very expressive figurines of bulls, sometimes harnessed to carts, and wild and domestic animals were made from clay and stone. At least some of them could have been toys.

Small stone and metal sculptures of men and women are distinguished by their great resemblance to life, which well convey the anthropological type of at least part of the bearers of the Harappan civilization. The most famous is a fragment of a sculptural image of a bearded man in a diadem, in a robe decorated with relief trefoils. The squinting of his eyes resembles the position of the eyelids of a meditating person.

Making stamps

The real masterpieces were stamp seals made mainly from soapstone, intended, as the found prints show, for sealing goods, although it is very likely that they were also perceived as amulets and talismans. They are flat, square or rectangular, with a protrusion with a hole on the back. A few samples are round; There are practically no cylinder seals, so characteristic of Mesopotamia, Iran and other regions of Western Asia. As on the vessels, they depicted mainly plants and animals (“tur”, the so-called unicorn, humpbacked bull, tiger, crocodile, snakes, fantastic polymorphic creatures). In Mohenjo-Daro there are about 75% of such images. The images are in-depth, executed with great skill and understanding of body shapes, rendered close to life. As a rule, animals are depicted standing calmly near objects, which are interpreted as feeders or conventional symbols. In addition, samples were found with images of anthropomorphic male and female creatures in various poses, including those reminiscent of yogic ones. They are represented by participants in rituals. In addition to the image, a short inscription could be placed on the seals. There are seals with conventional geometric shapes.

The images on the seals are associated with holidays and rituals - feeding an animal, treating a snake, worshiping a tree in whose branches a goddess could be depicted, the marriage of gods in anthropomorphic and zoomorphic form. Judging by the available materials, the goddess played a major role in marriage myths. Images similar to those applied to seals are found on copper plates of unknown purpose. There were prismatic stone and clay objects, the belonging of which to the category of seals is questioned; perhaps they played the role of amulets. Seals could serve as signs of ownership, but there is no doubt that they also served ritual purposes, they were something like amulets, and the images on them contain information about mythological ideas and rituals. Research by W.F. Vogt of the seals of Mohenjo-Daro did not provide grounds for judging social differentiation among the population.

It is on the study of seals and related products that work on deciphering proto-Indian writing is based.

Writing and language

The study of the writing system and language of the Harappan texts has not yet been completed; Domestic researchers played a significant role in the research (a group led by Yu.V. Knorozov). The conclusions they reached are presented here based on the work of M.F. Albedil “Proto-Indian civilization. Essays on Culture" (Moscow, 1994). The difficulty of understanding the texts lies in the fact that they are written in an unknown script in an unknown language, and there are no bilinguals. About 3000 texts are known, lapidary (mostly 5-6 characters) and monotonous. The letter was hieroglyphic (about 400 characters), written from right to left. It is believed that the texts were of a sacred nature.

It turned out that early texts were written on stone plates, then on stone, and less often metal seals. The existence of cursive writing is not ruled out. When interpreting the signs, pictograms of the modern peoples of India, primarily the Dravidian-speaking ones, were used.

The researchers believe they have deciphered the general meaning of most of the inscriptions and identified the formal structure of the grammatical system. Comparison with the structure of languages hypothetically existing in the Indus Valley led to the exclusion of all but Dravidian. At the same time, scientists consider it unacceptable to mechanically extrapolate the phonetics, grammar and vocabulary of historically recorded languages into Proto-Indian. Reliance is placed on the study of the texts themselves, and the Dravidian elements are used as a “correction factor”. Translation is based on the semantic interpretation of the sign, which is determined by the method of positional statistics. They also turned to Sanskrit, as a result of which it was possible to identify the correspondence of 60 astronomical and calendar names and the structural correspondence in the names of the years of the 60-year chronological cycle of Jupiter, known only in the Sanskrit version.

It is assumed that the text block consisted of the name of the owner of the seal in a respectful form, explanations of a calendar and chronological nature and an indication of the period of validity of the seal. There is an assumption that the seals of officials belonged to them temporarily, for a certain period.

Judging by the deciphering of the texts, the solar agricultural year began with the autumn equinox. There were 12 months in a year, the names of which reflected natural phenomena; “micro-seasons” were distinguished. The astronomical year was based on four fixed points - the solstices and equinoxes. New moons and full moons were revered. The symbol of the winter solstice, the beginning of the year, is believed to have been the tour. There were several subsystems of time reckoning - lunar (hunting-gatherer), solar (agricultural), state (civil) and priestly. In addition, there were calendar cycles - 5-, 12-, 60-year; they had symbolic designations. These are the assumptions of domestic researchers of proto-Indian texts.

The problem of exchange and trade

For a long time, in the science of antiquity there was an idea of greater or lesser isolation and self-sufficiency of ancient social formations, in particular the Harappan ones. Thus, W. Ferservice wrote that trade played a large role in Sumer, a somewhat smaller role in Egypt, and the Harappan civilization was in a state of isolation and trade relations were random, not systematic. Later, in the 70s of the 20th century, the attitude towards the role of exchange and trade in antiquity changed dramatically, especially in foreign science. Reconstructions of not only the economy, but also the social structure of ancient societies that were unliterate or did not have informative written texts began to be carried out taking into account the role of exchange, not at the local level, but over long distances. Now some researchers attach great importance to the role of trade in the formation and existence of the Harappan civilization. In particular, a number of Indian scholars believe that traders played a large role in the formation of cities and ideological ideas, and they consider the disruption of trade with countries west of Harappa to be the reason for the decline of cities. Researchers (including K.N. Dikshit) associate the decline of trade in the later period with the weakening of central power, as a result of which trade routes became unsafe. The change in the political situation in Mesopotamia and the rise to power of Hammurabi caused the weakening of the cities of Southern Mesopotamia, and trade routes began to be reoriented to the west, to Anatolia and the Mediterranean. Cyprus became the source of copper, and not, as before, Oman and its neighboring territories.

Trade with Western countries

The existence of connections between the bearers of the Harappan civilization and their close and distant neighbors cannot be doubted, primarily because the Indus Valley, its indigenous territory, like Mesopotamia, is poor in the minerals that people needed and used. Minerals and shells came from the subcontinent and were widely used in various industries. Copper was delivered from more distant areas (its deposits were exploited in Iran, in particular in Kerman, and Afghanistan) and gold. Tin, as currently available information allows us to judge, came from Central Asia (one of the supposed sources is the Fergana Valley, the other is located in the southwest of Afghanistan), lapis lazuli - from Badakhshan (if not from the Chagai Mountains), turquoise - from Iran. Already in Neolithic Mehrgarh, connections with Iran are clearly visible, from where widely used minerals were delivered - crystalline gypsum (“alabaster” of archaeological literature) and steatite. The appearance of Late Harappan settlements in the foothills of the Himalayas may be connected precisely with the need of civilization for mineral raw materials - in one of the settlements traces of the production of various beads were found, clearly intended for exchange.

Already at the end of the 4th millennium BC. the names of southern countries began to appear in Mesopotamian texts - Dilmun, Magan, Meluhha. There have been and continue to be debates about their localization in science. Probably during the 3rd-2nd millennium BC. they meant different territories. However, it is clear that Dilmun and Magan were intermediate between Mesopotamia and Meluhha - the supposed Indus Valley. Dilmun (Bahrain) always played an intermediary role, while the real sources of the much-valued copper, wood, and minerals were not always known to the inhabitants of Mesopotamia, and their source could be considered the point where they received them - Dilmun. Thanks to discoveries in recent years, it has become clear that Oman was one of the important suppliers of copper to Mesopotamia. Standard copper ingots weighing about 6 kg are typical of finds of this kind from Syria to Lothal. It is noteworthy that the peak of information about this exchange occurs during the heyday of Harappa, around the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. Harappan type seals have been found in Ur, Umma, Nippur, Tell Asmara, on the Persian Gulf Islands, Bahrain and Failak, on the coast of the Arabian Sea. An inscription in Harappan script was discovered in Oman. The carriers of another culture, kulli, were also associated with the western regions - products typical of it were found in Abu Dhabi.

In Lagash at the end of the 3rd millennium BC. lived Harappan traders with their families. There have also been suggestions about the existence of Mesopotamian colonies on the territory of Harappa, although direct data on this matter is still insufficient. Everyone is surprised by the extremely small number of things characteristic of the Mesopotamian civilization on Harappan territory. This is usually attributed to the fact that they could be made from short-lived materials; Fabrics are mentioned among the likely imports. Perhaps the absence of foreign things is a consequence of the Harappans’ strong commitment to their traditions: researchers recall that in the houses of Indian merchants in the 19th century. It was rare to find things of foreign origin.

The sea route was most likely used - there are known images of sailing ships that were built from wood and reeds. The voyage was coastal, the sailors did not lose sight of the shore. There is an opinion, although not shared by all researchers, that the port was Lothal in Gujarat, where a structure similar to a dock was discovered. A seal typical of the Persian Gulf region was found at Lothal.

Trade with the Nordic countries

Exchange with nearby territories could be direct, and with distant ones - indirect. At the same time, the discovery of a real Harappan colony in Northern Afghanistan, near the confluence of Kokchi and Amu Darya, is symptomatic. It is believed that Shortugai was a “trading point” on the route connecting Harappa with the territory of Turkmenistan and other neighboring regions. One of the likely objects of interest of the “Harappans” is lapis lazuli, and possibly tin. The inhabitants of Shortugay brought lentils and sesame from India; the local crops they cultivated were grapes, wheat, rye and alfalfa; they raised zebu and buffalo from their native places. At the settlements of the Anau culture of Southern Turkmenistan, seals of the Harappan type, ivory products were discovered, and there are signs characteristic of Harappan products in the shapes and decoration of ceramic vessels.

Land routes ran north through mountain passes, bypassing the Dashte Lut desert into the Diyala valley, along river valleys within their territory, possibly along the coast - Harappan settlements were found on the Makran coast. It is unlikely that carts drawn by oxen, models of which made of clay and bronze were found in different settlements, were used for long journeys. But already in the period of the developed Harappa, they began to use Bactrian camels, which are believed to have been domesticated in Central Asia, data on which were obtained in Southern Turkmenistan, where the camel, according to existing assumptions, was domesticated back in the 4th millennium BC. In exchange operations, they used mainly cubic stone weights weighing 8, 16, 32, 64, 160, 200, 320, 640, 1600, 3200, 6400, 8000 g. Conical, spherical, and barrel-shaped weights were also used. Rulers with measuring divisions were also used.

The question of the place of foreign trade in the economic life of the Harappans remains debatable. Was it an essential or peripheral part of the economy? Was it a more or less regular exchange or was it a planned trade? How were the products of internal exchange realized in it? Was the trade directed by "government administrators" or professional agents?

As with the study of other areas of Harappan culture, the answer to these questions depends on the reconstruction of the social order as a whole, the understanding of which is far from clear. Nevertheless, it is hardly justified to conclude that trade and production of goods differed little from modern ones.

Social structure

Researchers of large Harappan settlements, from the moment their structure became clear, expressed, on the basis of the division of these settlements into two or more parts, an assumption about the division of society into the nobility - the inhabitants of the “citadels” and the rest of the population. Some researchers interpret the inscriptions on clay bracelets as titles. M. Wheeler saw an analogy to the social organization of Harappa in the city-states of Mesopotamia, and considered the idea of cities brought from Sumer. Many scholars have written about the Harappan "empire" with centralized power and an exploited rural population. They also assumed the existence of several classes - an oligarchy, warriors, traders and artisans (K.N. Dikshit), rulers, farmers-traders, workers (B.B. Lal), to which some added slaves. M.F. Albedil wrote about the possibility of a highly centralized political structure in proto-Indian society. At the same time, it allowed for a strong role for local centers, in which central power was partially duplicated locally. Some researchers rightly focus attention on the specifics of Harappan society, in particular on the place of the priesthood in public life, which was different than in Mesopotamia with its organized temple households. Nevertheless, there are reasons to believe that at least at some stages, especially during the developed Harappan period, there could have been a strong ruling elite consisting of priests. Based on the decipherment of documents of proto-Indian writing proposed in Russian science, one can assume the functioning of temples and priesthood and even the presence of political leaders.

So, the data does not allow us to draw direct parallels between the social organization of Mesopotamia or Elam and that of the bearers of the Harappan civilization. Until now, despite a significant volume of excavations, no signs of the existence of rulers and individuals who concentrated in their hands significant material values, deposited, in particular, in burials, as was the case in Mesopotamia or Egypt, have been discovered. The weak manifestation of the military function in society is symptomatic. Apparently, significant wealth was not concentrated in the temples. Business documents were not found or were not identified.

At the same time, there are facts indicating the existence of property inequality, the presence in society of groups that occupied different social positions and performed different functions. The accumulation of values is suggested, in particular, by treasures discovered in Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and other places. W. Ferservis, taking into account the peculiarities of the Harappan civilization, drew attention to the large number of short-term settlements and the significant role of livestock breeding, which could act as a symbol of wealth. Settlements in a particular area played different roles - among them were predominantly agricultural ones and those in which craft production and exchange predominated. These settlements were interconnected. He suggested that the form of organization was not a city-state or a single state, but chiefdoms. According to his hypothesis, the Harappan chiefdoms were based on kinship ties and were similar to those known in Hawaii, Northwest America, Southeast Asia and West Africa.

The degree of development of cities, crafts and economy, the formation of its specialized forms, agriculture and cattle breeding implied the need to regulate relations between representatives of different spheres of activity. The circulation of “primitive values”, traced, in particular, through the example of lapis lazuli products, led other researchers to the assumption of the formation of formations such as chiefdoms already at the early stage of Harappa. In the future, the emergence of a state is assumed in which power was no longer associated with genealogical rank, and relations of production were separated from relations based on kinship. The use of the concept of chiefdom to reconstruct the social structure of pre-state societies in the East has raised objections. As an alternative, another model was proposed, based on the study of acephalous societies of the Eastern Himalayas (in Russian science, its development belongs to Yu.E. Berezkin). Farm type: irrigated agriculture and cattle breeding. Signs of such societies, some of which can be discerned in archaeological material, are expressed in the appearance of settlements. These are closely built-up villages without monumental architecture with many small sanctuaries, the existence of differences in property status that can be overcome thanks to a special institution of redistribution such as the potlatch, specialized crafts, trade exchange, obtaining exotic prestigious things through trade over long distances. These are not chiefdoms, but neither are they groups of closed village communities. At the same time, community and clan institutions were weak, and the individual, thanks to individual ownership of the means of production, was independent. Social life is regulated during mass ceremonies and celebrations, during which complex systems of relations developed, covering the entire area of residence of the ethnic group. In the villages there were councils of respected men. It cannot be ruled out that the society of the Harappan civilization without a layer of elite and with public buildings that required relatively little labor could have been more likely to be similar to those described, but on a larger scale. It should be noted that before and, what is especially noteworthy, now, with the advent of new data, opinions are being expressed about the existence of the state.

Religious and mythological ideas and rituals

It is difficult to judge the myths, beliefs, rituals, as well as the spiritual life of the “Harappans” in general, primarily due to the low information content of written monuments, even if we recognize the accuracy of their interpretation. The sources are primarily images on seals and other things, samples of clay, stone, and metal sculpture, traces of rituals. Temples - one of the main evidence of the veneration of the gods - did not exist or are not identified. One of the grounds for reconstructions is a comparison of known data with the ideas and rituals of the supposed historical successors of the bearers of the Harappan civilization or, as many researchers are inclined to think, the Dravidian-speaking peoples of India related to them in language.

Animals depicted on seals and metal plates: humpbacked Indian bull, gaur bull, buffalo, an animal similar to a bull, but depicted with one horn (“unicorn”), tiger, rhinoceros, crocodile, elephant, rarely a rabbit, birds, fantastic multi-headed animals, according to domestic researchers, served as symbols, some of them - cardinal directions and/or seasons. Trees were also depicted - peepal, ashwattha. The tree is sometimes depicted rising from a ring-shaped enclosure - it probably served as an object of worship, embodying the idea of a “world tree” (enclosures of this appearance were discovered during excavations). In later times, revered trees were decorated, in particular, in order to have children. Sacrificial rituals played an important role.

A seal depicting a horned figure, possibly a yogi, either proto-Shiva or Pashuvati (lord of animals).

There are known images of anthropomorphic female and male creatures, found, in particular, in scenes of their worship. One seal depicts a horned male figure, whose pose, according to J. Marshall, resembles that in which Shiva was depicted. E. Düring Kaspers pointed to images of a horned and tailed character with a bow, which, in her opinion, evidenced the existence of hunting rituals. Female creatures, images of which are also known in small plastic works, are usually associated with images of “mother goddesses”. Apparently, there were many such mythological creatures; they were, at least in part, associated with fertility cults and ideas about life and death. Among the gods, they suggest the predecessors of Skanda, creator gods, spirits - the predecessors of the Yakshas, Gandharvas, Apsaras. There were rituals of sacred marriage, perhaps performed seasonally.

Research by Yu.V. Knorozova, M.F. Albedil and other domestic scientists suggest the veneration of celestial bodies based on deep knowledge of astronomy and observations of natural phenomena. Famous sculptures of men and women most likely depicted priests and performers of ritual dances. There is evidence that rituals were carried out in open courtyards; in Kalibangan, on the “citadel”, something like fire altars was discovered near the platform. Podiums with signs of cattle sacrifices were found. It is very likely that shamanic-type rituals and corresponding ideas exist. The images of bull hunters may be associated with ancient ideas inherent in hunters; The image of people jumping over a buffalo is interesting (W. Ferservis suggested the possibility of Cretan influence on this image made in an unusual linear style, which requires new confirmation). Cult objects were conical and cylindrical stones - something like lingas and ring-shaped objects - possible predecessors of the yoni.

Many researchers have no doubt about the profound influence of the religious practices and ideas of the bearers of the Harappan culture on the later ones brought by the Aryans. These include, in particular, the practice of yoga.

In general, the interpretation of the evidence of the Harappan religion, as well as the social system, depends on the position of the researcher:

- if we assume that society was organized hierarchically, and civilization was a holistic entity, we can talk about a pantheon, a priesthood with a hierarchy, etc.;

- if we assume that the organization of society was archaic, then we will have to talk about the diversity of ideas and religious life, even if they have a certain commonality.

Disappearance of the Harappan civilization

According to tradition, there are two reasons why the Harappan civilization could have disappeared -

- change in climatic conditions, and, as a consequence, change in the course of the Indus

- the arrival of other ethnic groups in the Indus Valley, and in particular the Aryans.

You can read in more detail what could have happened in.

Be that as it may, the role of the Harappan civilization in the history of India is still truly difficult to determine, although, following many researchers, it can be regarded as extremely important. Among the preserved heritage there are forms of traditional way of life, social structure, a significant array of religious ideas and rituals. It is assumed that the four-varna division and the caste system were formed under the influence of non-Aryan ethnocultural substrates.

The civilization that arose in the Indus River Valley and surrounding areas is the third oldest, but least studied of all early civilizations. Its writing has not yet been deciphered, and therefore extremely little is known about its internal structure and culture. It quickly declined after 1750 BC, leaving little as a legacy for subsequent communities and states. Of all the early civilizations, it lasted the shortest period of time, and its heyday probably lasted no more than three centuries after 2300 BC.

The first evidence of agriculture in the Indus Valley dates back to 6000 BC. The main crops were wheat and barley - most likely adopted from villages in southwest Asia. In addition to these, peas, lentils and dates were grown here. The main crop was cotton - this is the first place in the world where it was regularly cultivated.

Among the animals kept here were humpbacked cows, bulls and pigs - apparently domesticated local species. Sheep and goats, the main domestic animals of Southwest Asia, were not of great importance in the Indus Valley. From about 4000 BC, as the population grew, mud brick villages began to be built throughout the valley and the culture became homogeneous. The main problem for the early farmers was that the Indus, fed by water from the Himalayas, flooded large areas of the valley from June to September and changed its course frequently. From 3000 BC Extensive work was carried out to retain flood water and irrigate adjacent fields. When the waters subsided, wheat and barley were planted and harvested in the spring. The result of increased irrigated land and flood control was an increase in food surpluses, leading to rapid political and social development from 2600 BC. and to the emergence of a highly developed state in one, maximum two centuries.

Map 9. Indus Valley Civilization

Very little is known about the process that led to the emergence of this civilization and about its nature. Neither the names of the rulers nor even the names of the cities have been preserved. There were two cities - one at the excavation site in Mohenjo-Daro in the south, the other in Harappa in the north. At their height, their population may have numbered 30,000 to 50,000 (roughly the size of Uruk). However, in the entire 300,000 square miles of the Indus Valley, these were the only settlements of this size. The two cities appear to have been built according to the same plan. To the west was the main group of public buildings, each oriented north-south. In the east, in the “lower city,” there were mainly residential areas. The citadel was surrounded by a brick wall, the only one in the entire city. The streets were laid out according to a plan, and the buildings were built of brick according to a single pattern. Throughout the valley there was a single system of weights and measures, and there was also uniformity in artistic and religious motifs. All these features indicate a high degree of unity of the society that inhabited the Indus Valley.

The Indus Valley Civilization was at the center of an extensive web of trade connections. Gold was delivered from Central India, silver from Iran, copper from Rajasthan. Several colonies and trading posts were founded. Some of them were located inside the country on strategically important roads leading to Central Asia. Others controlled access to major resources, such as timber in the Hindu Kush Mountains. The strong influence of this civilization is demonstrated by the fact that it maintained a trading colony at Shortugai, the only known deposit of lapis lazuli, on the Oxus River, 450 miles from the nearest settlement in the Indus Valley.

Trade connections extended even further to the north, to the Kopetdag mountains and Altyn-Tepe on the Caspian Sea. It was a city of 7,500 people surrounded by a wall 35 feet thick. The city, with a large artisans' quarter, had 50 kilns. He engaged in regular trade with the Indus Valley.