Tuchkovs. Russian duelists

Nicholas I unveiled a monument to the heroes of the Battle of Borodino on the Borodino field. This morning of August 26, 1839 was as fresh and clear as the morning of the Battle of Borodino. Nature initially separated from people and did not want to take part in their madness and killing each other. She does not need fame or wealth: the whole earth is her Fatherland, therefore the same bright, yellow sun rose over Borodino twenty-seven years later, and the autumn freshness was also sensitive.

Thousands of sparkles were mixed together: bayonets, helmets, stars and epaulettes of generals, sewing banners. Troops, about 120 thousand, surrounded in columns on three sides the elevation with the monument to the Battle of Borodino, at the foot of which Bagration rested. In this place in the twelfth year there was the hottest battle, when people, having already lost hope of destroying each other with cannons, mixed up in a hand-to-hand murderous battle.

From this place one could especially see and feel the enormity of the field, which contained so many living and dead.

The infantry was motionless, the cavalry, on the contrary, like a living mosaic, was constantly in motion: the horses looked at each other, danced impatiently, and trampled the still green, lush grass with their hooves.

In the center of the parade, near the fence of the monument, retired soldiers, participants in the battle, who had arrived for this holiday from different places, gathered. Disabled people sat on the steps of the monument in anticipation of the celebration. Crutches and sticks lay nearby. Among them, the excitement that reigned in the parade troops was not noticeable; they languidly exchanged words, squinted in the sun, and rested.

And yet, it was they who formed a single monolith on the field, an indivisible whole of which, in parts, this day and these new troops lined up in columns were echoes. The past, which overshadowed their previous life, laid its hand on their entire future, the past, which consisted of only one day - the Battle of Borodino, united them, made them look like one tired and wise person.

Borodino soldiers, still in service, lined up outside the fence. They combined the past and the present and therefore looked apart, completely not belonging to either the young troops or the disabled. But then the emperor appeared. I galloped past the columns, and a ubiquitous “hurray” flew into the air, even louder, louder... and suddenly everything became quiet. Slowly, solemnly and discordantly, with banners and a cross, a church procession stretched from Borodin.

...An elderly nun stood at the fence of the monument, clutching the steel bars as if her legs could not support her; she gazed intently at one point, and the bewitching, intense gaze of her dark green eyes expressed only inner, painful concentration and cherished, protected grief. No one spoke to her; looking at her, everyone felt a feeling of awkwardness. Eyes were averted, and memories: smells, colors, fragmentary pictures - suddenly rolled in like a suffocating wave of gunpowder, and the sun dimmed under a smoke screen, and the crunch of a bayonet entering a human body was heard. And the retired soldier reached for tobacco, looked again at the nun and could not understand why it was from her, and not from the solemn speeches, not from the ceremonial gunfire, that the past weighed heavily on him.

The names and activities of the Tuchkovs have never been the subject of loud conversations, fame and praise. Apparently, by nature and upbringing, they considered honor and fidelity to duty to be a common and natural thing for the human heart, they never singled out or qualified their actions, and they themselves were so alien to admiration for their deeds that for their contemporaries their valor and activity had the character of something... something normal, a matter of course. Little known during their lifetime, they were immediately forgotten after death. The names of many heroes have reached us from the past; poets, historians and writers told us about their exploits. There is almost nothing about the Tuchkovs. This is what happened with Sergei Alekseevich, the middle brother, a writer, thanks to whom people of that time could expand their knowledge about such “little-known” and “dark” lands as Bessarabia, Georgia, Lithuania. Along with Pushkin, who was “fascinated by his intelligence and courtesy,” Lermontov, he carried out a noble mission - to convey to the Russian inhabitants the image, customs and culture of these original lands. The founder of an entire city in Bessarabia, named after him, a participant in four wars (including 1812), about whose courage and stewardship Suvorov, lieutenant general, senator, spoke more than once.

Little is known about the feat of Pavel Alekseevich Tuchkov, one of the brothers, who “contrary to the command clearly stated in the disposition,” started a battle that went down in history as Lubinsk. The French failed to cut off the First Army from the Second and push it back from the Moscow road. Chopped with sabers, he was captured and lived for three years in a foreign land.

The name of the oldest brother, Alexei Alekseevich Tuchkov, is missing in all encyclopedias, including modern ones. In “Notes,” his son Pavel Alekseevich writes that his grandfather, Alexei Vasilyevich Tuchkov, a senator, had five, not four, sons. The oldest of them was Alexey Alekseevich, member of the State Council, lieutenant general. Due to troubles with the minister of that time, Count Arakcheev, he left military service and, retiring in the village, devoted his life to children. The eldest, named, like his father, Alexei, became a Decembrist. He was friends with N.P. Ogarev and A.I. Herzen, was arrested twice on charges of belonging to a “communist sect,” and his youngest son, the author of “Notes,” Pavel Alekseevich, was a prominent topographer of that time. A favorite of the Russian emperors, he was able to refuse the appointment as governor of the Kingdom of Poland due to the fact that he was not able to “...remove his involuntary trust in others...”. At the end of his life, he wrote a biography of the Tuchkovs, to whose name he was born “from an early age with pride to belong.”

The Tuchkovs are a noble family, originating from the Novgorod boyars evicted under John III to the interior regions of Russia.

The Tuchkovs' ancestor, Mikhail Prushanin (or Prushanich), left Prussia for Novgorod at the beginning of the thirteenth century, died there and was buried in the Church of St. Archangel Michael, on Prusskaya Street. His son, Terenty Mikhailovich, was a boyar under the Grand Duke Alexander Nevsky and distinguished himself in the famous Battle of the Neva on July 15, 1240. His great-great-grandson Boris Mikhailovich Morozov had the nickname Tuchko.

The niece of his son Vasily Tuchkov was later the great-grandmother of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov. The son of Vasily Borisovich, Mikhail, a boyar of Grand Duke Vasily Ioannovich, was sent as an ambassador to foreign lands several times. Mikhail's grandchildren - Ivan, David, Ermolai Stepanovich.

The Tuchkov brothers came from them.

Yermolai's great-great-grandson, Alexey Vasilyevich, an associate of Rumyantsev, an engineer-lieutenant general under Catherine II, and a senator under Paul I, commanded the fortresses along the Polish and Turkish borders. Under his supervision, a permanent wooden bridge across the Neva was built, and is still called “Tuchkov”. He was married to Elena Yakovlevna, née Kazarina, and had five sons and two daughters. Died in 1799, on the twentieth of May.

The coat of arms of their family is a shield divided perpendicularly into two parts; on the right is a warrior holding a spear raised up in one hand and a shield in the other. On the left side on a blue field is a lion standing on its hind legs and turned to the right. A cloud is visible above him, from which lightning flies out, striking the lion.

By getting to know the life of the Tuchkov brothers and determining their significance for Russia in the 19th century, we simultaneously receive the key to the origins of their deeds. The experience, level of self-awareness, and valor of the ancestors are necessarily manifested in the descendants.

Everything in their lives was harmonious, clear, and strict; their destinies were naturally and firmly intertwined with the fate of Russia, and the impossibility of a different path and a different fate is obvious.

Their path, walking “the path of truth, encountering obstacles from the favorites of blind happiness, reflecting slander and malice, was difficult, and if the reward of merit was not the lot of all of them, then in return some were destined for a reward from above: to die for the glory of their Fatherland.”

Warrior Nikolai

He was born in 1765, April 16th. At the age of eight, according to the custom of that time, he was “enlisted for military service” and released as an officer in 1778. His father, Alexey Vasilyevich Tuchkov, a military engineer, blessed his son to serve, as he considered the rank of military man the best and most worthy fate for all his sons.

And nothing in the fate of Nikolai Tuchkov until his death could change the decision once made.

He began his combat career in the Swedish War of 1788–1790, at the age of 23. After this campaign he was transferred to the Murom Infantry Regiment; participated in the war against the Polish Confederates.

In 1794 he distinguished himself in the battle of Matseevich. Commanding a battalion of the Velikolutsk Regiment, Nikolai Tuchkov showed not youthful daredevilry, but cold-blooded, mature courage. General Fersen, appreciating the qualities of the young warrior, as a sign of his favor, sent him with a report to the Empress, who personally awarded him the St. George Cross for excellent service and congratulated him on the rank of colonel.

During the campaign of 1799, during the war with France, Lieutenant General Tuchkov, being in Rimsky-Korsakov’s corps, after the unsuccessful Battle of Zurich, showed courage and managed, together with the Sevsky Regiment, to break through the enemy’s ring and reunite with Suvorov’s main army.

He also took part in the Russian-Prussian-French war of 1805–1807. He was the commander of the right wing of Bennigsen's army and distinguished himself in the battle of Preussisch-Eylau. In the Russian-Swedish war of 1808–1809 he commanded a division with no less distinction.

Nikolai Alekseevich participated in almost all the wars that befell his life. Always among the soldiers, a beloved general, he did not allow himself any privileges on the battlefield. His awards and ranks were earned at the cost of his entire life.

“He is short, pockmarked, dexterous in handling and has a secular education. A warrior at heart, with his remarkable military talents, he had an enlightened mind and an attractive manner. But the distinguishing features of his character were strict unselfishness and unshakable straightforwardness. Alien to all personal benefits... he thought only about the conscientious performance of his duty... Nikolai Alekseevich enjoyed the respect of the entire army, and his memory will be preserved forever in the military annals of Russia.”

When the Patriotic War of 1812 began, N. A. Tuchkov was appointed to the 1st Western Army, commander of the 3rd Infantry Corps, which consisted of the 1st Grenadier and 3rd Infantry Divisions. His younger brother Alexander was appointed to the latter position under the command of Count Konovnitsyn. Retreating with his troops first to Vilna, then to Vitebsk, participating in the battle of Ostrovno and in the battle of August 5 near Smolensk, among his corps, Konovnitsyn’s division and Nikolai’s younger brother Alexander most distinguished themselves.

... “On the evening of the 6th, Barclay de Tolly crossed from the Porechenskaya road to the Moscow road.” Ahead of the column entrusted to Nikolai Alekseevich was the vanguard under the command of Major General Pavel Alekseevich Tuchkov. On this day the three brothers saw each other for the last time.

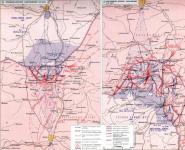

After the battle of Lubin, Nikolai Tuchkov headed to Borodin and settled down as a corps near the village of Utitsa so that the enemy could not bypass the Russian troops along the Old Smolensk Road.

Tuchkov's corps was supplemented by seven thousand people from the Moscow militia. It is possible that his elder brother Alexey Alekseevich, at that time the leader of the Zvenigorod district of the Moscow province, took part in the gathering of the militia. Kutuzov gave the order to place Tuchkov’s corps secretly, in the bushes, under a high mound. The corps was supposed to surprise the French if they began to bypass the left wing.

“When the enemy uses his last reserves on Bagration’s left flank, I will send a hidden army to his flank and rear,” said Kutuzov. Chief of Staff Bennigsen ordered otherwise. Driving around in the evening, on the eve of the battle, the troops ordered Tuchkov to come out of hiding and stand on the mound, complaining that it was necessary to give such stupid orders to someone (meaning, of course, Kutuzov) and leave the height not occupied by our troops . Tuchkov objected because he had a different order, but was forced to obey the repeated order.

Soon after the start of the battle, Prince Bagration ordered N.A. Tuchkov to immediately send Konovnitsyn’s division to his aid. Tuchkov immediately did this, although formally he could not have obeyed, since he was under the command of Barclay de Tolly. Konovnitsyn’s division, which included his younger brother, rushed to the aid of Bagration, and Nikolai Alekseevich remained with a detachment of three thousand to hold back the onslaught of Poniatovsky’s corps. A struggle for heights began near Utitsa. During the entire attack, Nikolai Alekseevich was in front of the regiment. The height was taken from the French, “but a bullet pierced Tuchkov’s chest, and they carried him dead from the battlefield.”

For a long time there was a suspicion on N.A. Tuchkov that “he did not know how to hold on.” Kutuzov, not knowing that his order had been canceled by Bennigsen, doubted the general’s courage.

“Notes” of Shcherbinin, together with other materials from the Military Scientific Archive of the General Staff, published by the military researcher of 1812 V. I. Kharkevich in 1900, show us the true state of affairs.

It turns out that only at the beginning of 1813, two months before his death, Kutuzov learned about Bennigsen’s arbitrariness and the innocence of Tuchkov, “who himself was killed on the spot, and therefore it was easy to blame him.” But what was more relevant here: the formalism of Bennigsen, who was “overwhelmed by an invincible need to get involved in everything and everyone,” and “who condemned everything that did not come from him personally,” or his conscious intrigues against Kutuzov, in whose place he dreamed of being, - unknown. And it’s not that important, because the battle was won, and Nikolai Alekseevich was killed.

The corps doctor bandaged the deep wound and winced at his uselessness. The adjutant and the soldiers carefully laid their general on his greatcoat and carried him from the battlefield. At the copse they were stopped by an officer who caught up with them on horseback.

He turned to the adjutant:

Still alive. My chest was pierced, you villain.

Yes... His brother was just killed at Semyonovsky’s.

The officer spurred his lathered horse and rushed back to where the ground rose, groaned and became increasingly soaked with blood like rain.

Having learned about his brother’s injury, Alexey Alekseevich, the eldest brother, rushed from Mozhaisk. He was in Mozhaisk on affairs of the militia and supplying the troops.

He carefully supported Nikolai's head while he was settled in the traveling carriage, and did not know how to tell him about Alexander's death. Imagine his surprise when the first request of the awakened Nikolai was “never, not with a single word, to remind him that his beloved Alexander is no more.”

From Mozhaisk Tuchkov was transported to Yaroslavl. He rarely regained consciousness and died in the Tolga Monastery after three weeks of suffering. He was buried there.

Unfortunately, only scant information about the life of Nikolai Alekseevich has been preserved. As a man who devoted himself entirely to military affairs, he almost did not live at home, was not married, and left behind no records, no memories, no letters, no diaries. Apparently, he simply did not have time for all this, nor did he have the desire. From the Tuchkov family legends it is known that he was an “exemplary relative”, of his relatives he loved his younger brother Alexander most of all and was the most beloved son of his mother Elena Yakovlevna, who, having learned of his death, went blind that same day.

Everyday mention of him was preserved only in the “Notes” of his nephew Pavel Alekseevich.

“...No work could intimidate me”

“...My father was always busy with enterprises in his Service,” he wrote in his “Notes,” “he was somewhat gloomy and not always friendly; such was the majority of the military people of that time; Moreover, he did not like to spend much time with his children when they were young. But he had a completely different attitude toward them at our other age.”<…>

“When I was three years old, they began to teach me to read from an old primer and catechism, without any rules. At that time, most of the middle nobility began to be educated in this way. Meanwhile, they did not fail to teach me how to make polite bows, accustomed me to French clothes, made a large toupee, several boucoles, and tied a wallet from my small hair. But this did not last long. The inexperienced hairdressers tore out all my hair and were forced to put a wig on me: moreover, the French caftan, sword and shoes represented me as some kind of small caricature and a bad copy of the Parisian resident of the century, Louis XIV.

Just like all his brothers, from early childhood Sergei was enlisted in military service, as a non-commissioned officer in the artillery, and after much hesitation by his parents, where he should be raised - in the cadet corps or at home, the latter was decided, and Sergei Alekseevich was released home for “passing the sciences.”

“They cut off my toupee that was beginning to grow, combed my hair into small curls, put a long braid in the back, put on a tie with a buckle, a narrow underwear and boots - and so from French clothes I was transformed into a little Prussian.”

Sergei's training took place first under the guidance of a sexton, then a local Lutheran pastor, who taught him German.

At this time, in 1777, his father Alexey Vasilyevich was the commander of the fortresses along the Polish and Turkish border, and the entire Tuchkov family moved to live in Kyiv.

“...Instead of dull Russian songs, ear-piercing, horns and hoarse pipes, I heard violins, harps and cymbals, and the singing of young men and girls, completely different from the wild tones of Russian songs. These Little Russian songs, composed without any science in all the rules of music, struck my ears...”

Here Sergei Alekseevich studied French, geography and history with his tutor. His father “... considered fencing and horse riding unnecessary and said: “I don’t want my children to fight,” or “Our Cossacks don’t know the arena, but they sit on horses stronger than other peoples and know how to control them without learning.” He considered literature to be a completely empty matter, as well as music... He wanted all his children to serve in military service. However, this opinion still prevails among the Russian nobility.”

“...Some of the young officers who made up the drafting office studied arithmetic, geometry, drawing with me and loved poetry. They brought with them various works and read them aloud to one another. Most of all I liked Lomonosov’s works... These works gave me a desire for poetry, I began to compose poems on occasion.”

At this time Sergei was 12 years old. A friend of their family, the rector of the Kyiv Theological Academy, liked the poems, and he sent them to the Moscow University Journal for publication. At the same time, despite his father’s dissatisfaction, Sergei Tuchkov is learning to play the flute.

Soon the entire Tuchkov family moves to Moscow, and Sergei has to give up the activities he loves.

In Moscow, Sergei Alekseevich reminds about the poems sent to the journal of Moscow University, and he is kindly accepted as a member of the “Free Russian Society, concerned about the dissemination of sciences.” He begins to prepare literary translations for a speech at the Society, but his father’s restless work once again takes him away from his pleasant occupation. In St. Petersburg, General F.V. Bour, head of the engineering corps, dies, and A.V. Tuchkova is soon appointed to his place for special merits and faithful service. The Tuchkovs moved to St. Petersburg. Here Sergei Tuchkov joined the “Society of Friends of Verbal Sciences,” among whose members Radishchev was.

At the age of 22, Sergei Alekseevich begins his active military service.

“Having received orders to set out with the company entrusted to me, I immediately made my orders and hurried to my father’s house to say goodbye to him and my mother.” Alexey Vasilyevich hugged his son and said: “Well, dear son, God bless you; Maybe we won’t see each other for a long time, here’s my advice: where they will send you, don’t refuse, and where they won’t send you, don’t ask for it; listen more than talk..."

“...Now I’ll tell you what form the army in Russia was in at that time, which had so glorified this state with its military actions. Empress Catherine, as a woman, could not deal with the organization in all parts of it, and therefore she left the care of the army to her generals, the generals had power of attorney to the colonels, and the colonels to the captains.

I also noticed that the soldier’s head was combed into several boucles. The beautiful grenadier cap and musketeer hat were only for show, but not for use. They were high and so narrow that they barely stayed on the head, and therefore they were pinned with a wire pin to the hair curled into a braid. The guns, in order for them to stand straight when the soldiers held them on their shoulders, had straight stocks, which was completely inconvenient for shooting. But the most intolerable thing was the inhumane bearing of the soldiers; There were colonels who, when handing over recruits to the captain, used to say: “Here are three men for you, make one soldier out of them...”

According to Sergei Alekseevich, there were many other abuses and tricks in the regiments, “but it must be said that regimental and company commanders are not to blame for these practices; they were required to pomp and splendor in maintaining the regiments, but were not given money. Doesn’t this mean putting all the regiments under the necessity of attempting to commit abuses?” This was the case under Rumyantsev. “Potemkin, having taken over, ordered all the soldiers to wash off the powder from their heads and cut their hair; instead of grenadier caps and hats, he invented a special kind of helmet, quite calm; instead of French uniforms, short jackets or camisoles with lapels.”

In the Swedish War of 1788–1790, Tuchkov took part in the naval battle of Rochensalm, August 13–14, 1789. His reputation as a brave warrior came at a high price. He was wounded in the arm, leg and head. Shell-shocked.

He returns to St. Petersburg and learns that the Society of Friends of Verbal Sciences is closed, and because of it, many other literary meetings are closed. “Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow” had such a strong effect on Catherine II that she ordered the execution of the author, although she later replaced the execution with lifelong exile. Other members of the “society” did not fare well either. They were arrested and the case was brought to court.

Combat courage saved Tuchkov from reprisals. When his name was mentioned among others, Catherine II limited herself to a pun that there was no need to “touch this young man, he is already in the galleys, making it clear that she is aware of his brilliant service in the galley fleet.”

Thus, for the second time, Tuchkov was faced with the fact that literature, little respected by his father, as an empty and useless activity, was an unsafe and very political matter. (The first case dates back to early childhood, when Sergei wrote an epigram about a general. The “retribution” was then carried out by his father.)

In the fall of 1790, he decided to resume his music studies. “To teach music, having returned to St. Petersburg, I hired a court chamber music musician, Mi, who, on Catherine’s orders, gave lessons to her grandchildren, Alexander and Konstantin.”

Once he told me: “It’s in vain that I take money for teaching the great princes; they will never be music lovers. The eldest grandson (Alexander) does not hear the chord well, and is insensitive and so secretive in his character that his real inclinations cannot be noticed, and this is bad for the sovereign. “The younger one,” Mi continued, “although he has a fair hearing, but when he hears the drum, he drops everything and runs to the window without memory. These are the first character traits of these great princes, noticed by the musician.”

At the age of 25, Sergei Alekseevich took part in the war with Poland of 1792–1794. “He is in Vilna in 1794 during the treacherous massacre of the Russians on Easter night. He takes 16 guns out of the city, saves the banners of the Narva and Pskov regiments, then in a bold offensive captures the Polish battalion.” For this feat, he becomes personally known to the empress and is awarded the Order of St. Vladimir 4th class and Georgy 4th class, while still with the rank of artillery captain.

As a military man, Sergei Alekseevich Tuchkov found both objects for criticism and role models mainly among his colleagues. The military genius of A.V. Suvorov could not help but arouse his admiration.

This is what he writes in “Notes” about the great commander.

“...Suvorov is so famous for all his merits, character and strangeness of actions that I have nothing left to say about him. Is it only that when Major General Arsenyev was returned from captivity (Vilna unrest of 1794 - M.K.) and was with him in the position of general on duty, then Suvorov, when he had any displeasure, used to say: “There are people who like to sleep a lot, and I heard that there are also those who never sleep.” Then, turning to the person who was with him, he asked: “Is it true that we have one artillery captain, as if he had never slept in his life?”

“Oh, how curious I am,” he continued, “to see this man and hear about it from him himself.” These words were the reason that I tried not to be introduced to this great man. I was afraid that he had confused me with such an unusual question.”

In 1796, Paul I ascended the throne. As always happens, when there is a change of ruler, new characters come onto the “scene” with the new king. New orders were introduced in the army and in social life. Here is a brief description of Paul's reign, given to us in the Notes,

“Often, someone who, without any other merit, salutes well with an exponent in a conversation, is awarded a promotion, an order, and sometimes an estate. On the contrary. His vile vengeance was immediately revealed against the officials who served under Prince Potemkin, Zubov and other favorites of Catherine, and then against the nobles themselves. The immortal Suvorov was also subject to this fate.” Emperor Paul ordered that the Russian army “be more like the Prussian one, which is observed to this day by his son Alexander.”

During the reign of Paul I, Tuchkov was ordered to suppress a peasant rebellion in the Pskov province. Sergei Alekseevich managed to pacify the residents without bloodshed, for which he was awarded the Order of St. Anna 2nd degree.

The instigators of the rebellion were persons of noble origin, “who acquired the right of nobility in Russia, which is not so difficult, and the clergy. Although I had full power to punish them, I did not want to transgress fundamental Russian rights. (Abolition of corporal punishment for nobles under Catherine II. - M.K.) May my reader forgive me that I thought so then and believed that some rights could exist in Russia. The sovereign, despite the fundamental rights by which the nobility and clergy are exempted from corporal punishment, ordered them to be flogged and sent to Siberia for hard labor ... "

Sergei Tuchkov’s ability to find a common language with people, to be fair and managerial was especially evident when he managed the civil part in Georgia, from 1802. This is what he writes about the events leading up to this important event.

“...George XII, the last Georgian king, did not know what would happen after his death, since some members of the royal house sought the patronage of the Persian and Turkish courts, had a strong party and outraged the people... Therefore, George decided before his death to make a spiritual decision, according to which he conceded He gives his entire kingdom to the Russian power...”

In 1802, Sergei Alekseevich was appointed civil governor of Georgia. All this time, according to Kolomiytsev, he “dealt with simple, poor people: he settled them, settled them and took all measures to improve their well-being.”

In the same year, a terrible disaster struck Georgia - the plague.

Sergei Alekseevich, with his characteristic energy, together with a small handful of people fought the epidemic, and “thanks only to this, it soon stopped.”

“...during the plague that was raging in this city, I took all life-saving measures to preserve them (the inhabitants. - M.K.) life and property. Having separated the healthy from the infected and released the first to a safe place, he was left with only those infected with the plague...”

In the first years of the reign of Alexander I, S. A. Tuchkov continued his brilliant activities in the Caucasus with the rank of general. At this time, he was composing an essay aimed at improving the well-being of Georgia, “Notes concerning the lands between the Black and Caspian Seas, and especially about Georgia.”

In 1807, Alexander, knowing Tuchkov’s remarkable military and civilian qualities, sent him to “pacify the Ukrainian police.” Unrest in the army began in response to the manifesto of Alexander I, according to which the emperor doomed the soldiers to almost indefinite service, although he had previously promised to disband home “once the danger from the French had passed.”

According to Sergei Alekseevich, Emperor Alexander generally “easily abandoned his promises,” but an order is an order, and Tuchkov set out to pacify the rebellion, guided in this case by his firm principles, one of which read: “There is no action without a reason, and therefore must discover the reason from the very beginning and consider whether it is true or false. In the first case, it must be consistent with the rights of the people, the state and mode of government. Although the reason is fair, any indignation is nothing more than arbitrariness, and therefore impermissible. And before taking measures of violence, it is necessary to prove to the rebels the wrongness of their act, and, depending on the circumstances, the impossibility of carrying out their undertaking. In the second case, just explain to them the injustice of the reason in order to convert them to proper obedience.”

This is the secret why, where others could not do without bayonets and sacrifices, Sergei Tuchkov gained good fame both among his superiors and his subordinates.

The last entries in this diary date back to 1808 and are devoted to the military situation in Russia, the court of Alexander I and “the characteristics of our generals.”

“I am not saying here how much our generals, being concerned only with external trifles in relation to the soldiers’ clothing, and others with report cards and papers, have lost the habit of the art of war. At every transition, in every movement, in setting up a camp and in leaving it, each time the field marshal found the most gross and unforgivable mistakes.”

Further, Sergei Alekseevich cites, so as not to be unfounded, a curiosity that happened to General Rtishchev during the war with Turkey of 1808–1812. The commander-in-chief, Prince Prozorovsky, ordered that at 4 o'clock in the morning a cannon shot be fired, which should begin a general march against the enemy in all corps of the army. S. A. Tuchkov personally conveyed this order to the adjutant of General Rtishchev. The cannon fired at two o'clock in the morning, causing a terrible commotion throughout the entire camp. When asked how this could happen, the frightened adjutant reported that he shot two on the orders of General Rtishchev, “so that the troops could better prepare for the morning march.” Rtishchev was removed from office. In his place, Sergei Alekseevich Tuchkov was appointed.

“It seems there is no one else here,” the commander-in-chief added, looking angrily at the generals.

In February 1812, Sergei Alekseevich managed to capture the pasha and more than 600 Turks. He was nominated by Kutuzov for the award.

The fact that Tuchkov built and settled an entire city in Bessarabia (1,500 houses and shops) without any costs to the treasury also dates back to this time. As a reward for this, the Senate decided to give the city the name “Tuchkov” in memory of posterity after the name of the founder (in the middle of the 19th century it became part of the city of Izmail).

When the Patriotic War of 1812 began, Sergei Alekseevich was still on the Turkish campaign, so he took part only in its second half. He was appointed to the responsible post of duty general of the Danube Army, under the command of Chichagov.

At the end of 1812 in Minsk, Sergei Tuchkov was put on trial and removed from his post. It can be assumed that the vile accusation that Adam Chartoryzhsky brought against him was not without the participation of the vindictive Arakcheev.

The enmity of Count Arakcheev with the Tuchkov family began in 1799. According to P. T. Kolomiytsev, in September of this year a theft was committed in the arsenal. The battalion of Arakcheev's brother, Major General Arakcheev 2nd, stood guard. Emperor Paul I entrusted Arakcheev with the investigation of the case. He hid the true state of affairs and accused the innocent commander of another battalion of “neglect.” His name remains unknown to us. The Emperor removed this honest man from service. But the retired man turned out to be not cowardly and, with the help of Sergei Alekseevich, who never put up with this kind of injustice, he ensured that Paul I learned the truth. On October 1, 1799, the following royal order was issued: “Lieutenant General Count Arakcheev 1st is dismissed from service for a false report of unrest, Major General Arakcheev 2nd is dismissed from service for the theft that occurred in the arsenal by his battalion.”

It is difficult to imagine the true participation of S. A. Tuchkov in this matter, but, apparently, it was significant if, having returned to power, Count Arakcheev during the reign of Alexander I created all sorts of obstacles, and in the twelfth year he was put on trial on false charges .

Tuchkov was accused of allegedly plundering the estate of the Polish princes Radziwill by the troops who were in his corps, and Tuchkov personally seized 10 million zlotys from the “victim.” The investigation lasted more than 12 years; it was proven that “an inventory was compiled of all the things and money taken by order of General Chichagov from the Radziwills, which, together with the property, was presented at the same time by Tuchkov to the commander of the Danube Army, General Chichagov.”

The strange thing is that General Chichagov was not involved in the case and in 1814 he went abroad. For the entire duration of the trial, Tuchkov moved to the city he founded and lived there in disgrace until his acquittal, which coincided with the death of Alexander I, in 1825.

During his disgrace, S. A. Tuchkov published a “Military Dictionary” containing “Engineering and artillery terms that a general needs to know for precise orders.” In 1816–1817, Works and Translations were published in 4 parts. The publication includes translations of odes by Horace, tragedies of Euripides, Februs, Afalia, Orestes and his own works: fables, sonnets, choruses, poems and stanzas written by Tuchkov over more than 20 years. Among the fables there is one concerning Arakcheev: “The Cock and the Starling.” Kokushka asks Starling what do people say about her?

“Nothing,” Starling replies, “it looks like they don’t know about you.”

Ah well! - said Kokushka, - so now I will repeat my name everywhere, endlessly. Cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo.

There is one little-known but remarkable fact in the life of Sergei Alekseevich Tuchkov.

In 1821, when he lived innocently convicted in the city of Tuchkovo, A.S. Pushkin visited Bessarabia. In Izmail, Pushkin wandered for a long time through the places associated with the Suvorov assault, and visited “the fortress church, where there are inscriptions of some of those killed in the assault.”

In the same city, at a dinner with Slavich, he met Lieutenant General S.A. Tuchkov. Pushkin spent the whole day with him, the whole evening, “he came home only at ten o’clock,” before nightfall, and what they talked about with the general remained unknown. Pushkin’s acquaintance I.P. Liprapdi, who accompanied him on the trip, wrote in his memoirs that Pushkin “was fascinated by him (Sergei Tuchkov. - M.K.) intelligence and courtesy” and admitted “that he would stay here for a month to see everything that the general showed him.”

It can be assumed that A.S. Pushkin learned from Tuchkov details about Radishchev, with whom Sergei Alekseevich was familiar from the “society of friends of verbal sciences” in St. Petersburg, as well as about the reign of Catherine II, Paul I and the circumstances of the murder of the latter.

Emperor Nicholas I remembered the old and faithful warrior and, in memory of his services, awarded the rank of lieutenant general and the Order of the White Eagle for his participation in the Turkish War of 1828 and for the excellent service of the mayor of Izmail. When Sergei Alekseevich was 63 years old, he became a senator. Physical and mental wounds made themselves felt. In 1834, he left the service, and soon Izmail did too. He moved to Moscow, closer to the only surviving brother of the entire family, brother Pavel Alekseevich, and died in 1839. He was buried in the Novodevichy Convent.

If we talk about the appearance of Lieutenant General S.A. Tuchkov, then from the only portrait that has survived, we can say that his nose was large and humpbacked, his chin was chopped and strong-willed, and the expression of his eyes and lips was soft, sad, dreamy. In general, the Tuchkovs do not look alike from each other. Although these faces have something in common: the attractiveness of loyal, active and honest people.

Well, this is, perhaps, all that can be told about the life of Sergei Alekseevich Tuchkov - a man who, in his own words, was extremely enterprising in life, and no work could intimidate him.

"Those who are ahead"

Pavel Alekseevich Tuchkov, the fourth son of Senator Alexei Vasilyevich Tuchkov, was born on October 8, 1775 in the city of Vyborg, where his father was the commander of fortresses near the Swedish border.

Alexey Vasilyevich intended his younger sons for military service. Pavel was enlisted in the artillery. During the Swedish War of 1808–1809 he was awarded the Order of St. for courage and stewardship. Anna 1st degree. In the battle on the island of Kimito, P. A. Tuchkov managed to save the commander-in-chief of the army, Count F. B. Buxhoeveden, and the duty general P. P. Konovnitsyn from Swedish captivity.

After the end of the war in 1809, Major General P. A. Tuchkov was with his brigade near Bergo and Lovisa and, by order of his superiors, remained there until December. At the beginning of 1812, Tuchkov was in the 1st Western Army of Barclay de Tolly. Unfortunately, this exhausts the meager information about the life of Pavel Alekseevich from the moment of his birth until the Patriotic War of 1812. But there are his personal notes about the war of 1812, first published in the Russian Archive in 1873: “...The Russians retreated. The main purpose of this retreat was the need to unite two armies: the 1st under the command of Barclay de Tolly and the 2nd under the leadership of Prince Bagration.”

This connection took place in Smolensk. From Smolensk the armies moved to Rudnya, in this movement P. A. Tuchkov was entrusted with a special detachment, from the Jaeger brigade of Prince Shakhovsky, the Revel infantry regiment under the command of A. A. Tuchkov and others. Then Barclay de Tolly changed this order and the armies returned to Smolensk.

On August 5, P. A. Tuchkov became “a witness to the courageous defense of Smolensk and the terrible destruction of this ancient city.”

The 1st Western Army stood the entire next day on the right bank of the Dnieper, 2 versts from the St. Petersburg suburbs, and in the evening of that day Barclay de Tolly decided to go out onto the Moscow road, almost in front of the enemy, fearing disunion with the 2nd Army. He divided the army into two columns: the left was led by Dokhturov, and the right by N. A. Tuchkov, Pavel’s elder brother. His path lay through Lubino.

Pavel Alekseevich's vanguard was supposed to go ahead of the right column, at night, and be the first to reach Lubino. Then, without stopping, his detachment had to go to Bredikhin. At first everything went as prescribed, but soon Pavel Alekseevich realized that by leaving Lubino, he was opening up an extremely important point to the enemy, the connection of the Moscow road with the country road, and that by occupying it, the French would be able to cut off the I Army from the II. And in the current situation this is tantamount to the death of the entire Russian army.

Pavel Alekseevich held in his hands a disposition, the violation of which threatened to be judged, but his conscience could not submit to formality.

He turned the detachment back and strengthened the position on the Moscow road. Now all that remained was to hold out there until his older brother’s column managed to cross from the country road to the main road.

Alexander Tuchkov, with his inseparable Revel infantry regiment, warmly supported his brother and stayed with him.

The adjutant sent to inform N.A. Tuchkov about the detachment’s intentions returned. N.A. Tuchkov knew about everything and sent two regiments to help the brave men. The three brothers understood each other perfectly and were united in their desire to defend their Fatherland. Therefore, many words were not needed for further instructions.

For four hours, Pavel Alekseevich’s detachment courageously repelled the advance of Marshal Ney’s corps and the troops of Murat and Junot who came to his aid. All French attacks were repulsed. In the evening of this day, all the Russian corps finally reached the main road. The army was saved, but the battle continued. Late in the evening, Ney once again tried to break through the center of the Russian forces, and Pavel Alekseevich led the regiment in a counterattack.

“...I had barely taken a few steps at the head of the column when a bullet hit my horse’s neck, causing it to rise on its hind legs and fall to the ground. Seeing this, the regiment stopped; but I, jumping off my horse, and in order to encourage the people, shouted to them to follow me forward, for it was not I who was wounded, but my horse, and with this word, standing on the right flank of the first platoon of the column, I led it towards the enemy, who, seeing our approach, stop, was expecting us to come upon him. I don’t know why, but I had a premonition that the people of the rear platoons of the column, taking advantage of the darkness of the evening, might delay, and therefore I walked with the first platoon, shortening my step as much as possible, so that the other platoons could not delay. Thus, approaching the enemy, already a few steps away, the column, shouting “Hurray!”, rushed at the enemy with bayonets. I don't know if the whole regiment followed the first platoon; but the enemy, meeting us with bayonets, overturned our column, and I, receiving a bayonet wound in the right side, fell to the ground. At this time, several enemy soldiers ran up to me to pin me, but at that very moment a French officer named Etienne, wanting to have this pleasure himself, shouted at them to let him do it.

“Let me go, I’ll finish him off,” were his words, and at the same time he hit me on the head with the saber he had in his hands. Blood gushed out and suddenly filled my mouth and throat, so that I could not utter a single word, although I was in perfect memory. Four times he dealt fatal blows to my head, repeating at each time: “Oh, I’ll finish him off,” but in the darkness and his passion he did not see that the more he tried to strike me, the less he succeeded in doing so: for I, having fallen, on the ground, lay with his head close to it, which is why the end of his saber, resting against the ground with every blow, destroyed almost it so that with all his effort he could no longer harm me, as soon as inflict light wounds on the head without damaging the skull . In this position, it seemed that nothing could save me from obvious death, for, having several bayonets pointed at my chest and seeing M. Etienne’s efforts to take my life, I had no choice but to wait for my last minute with each blow. But fate wanted to determine something else for me. Because of the clouds flowing above us, suddenly the shining moon illuminated us with its light, and Etienne, seeing the Annen star on my chest, stopping what had already been struck, perhaps the last fatal blow, said to the soldiers surrounding him: “Don’t touch him, this is the general, It’s better to take him prisoner.” And with this word he ordered me to be raised to my feet. Thus, having avoided almost inevitable death, I was captured by the enemy.”

One of P. A. Tuchkov’s contemporaries wrote about the fate of this battle and the personal qualities of Pavel Alekseevich as follows: “Tuchkov’s brilliant feat, absorbed ... by the enormity ... of events, was not adequately appreciated in its time. Subsequently, Emperor Alexander likened the battle of Lubin to the Battle of Kulm.”

In the French camp

“...No more than half an hour later they brought me to the place where the Neapolitan king Murat was, who, as you know, commanded the vanguard and cavalry of the enemy army. Murat immediately ordered his doctor to examine and bandage my wounds.

Then he asked me, “how strong was the detachment of our troops that were in action with me,” and when I answered him that there were no more than 15,000 of us in this case, he told me with a grin: “Tell others, others!” You were much stronger than that,” to which I didn’t answer him a word. But when he began to bow to me, I remembered that while I was being led to him, my brave Etienne, having heard a few words from me in French, began to earnestly ask me that when I was presented to the King of Naples, I would speak up about him although there is one word that will certainly make him happy. I didn’t want to pay him back with evil, bowing to the king, I said that I had a request to him.

Which one? - asked the king. - I will gladly do what you please.

Don’t forget about the awards given to this officer who introduced me to you.

The king grinned and bowed and said to me:

I will do everything possible - and the next day Mr. Etienne was decorated with the Order of the Legion of Honor.

The king ordered me to be sent, accompanied by his adjutant, to the main apartment of Emperor Napoleon, located in the city of Smolensk. With great difficulty we crossed the city bridge on the Dnieper that we had burned, which had somehow already been repaired by the French. At midnight they brought me to Smolensk and took me... into a room in a rather large stone house, where they left me on the sofa.”

The first days of captivity

Since the end of the 18th century, representatives of the Tuchkov family, prominent military figures during the Patriotic War of 1812 and their descendants, have played an outstanding role in the history of our settlements.

After the division with his brothers, Pavel Alekseevich Tuchkov (from the Tuchkovs’ numerous estates in other places) received the villages of Mukhino, Lyakhovo (there was a manor’s estate), Truteevo, Artyukhino, Brykino. The latter was destroyed during the Great Patriotic War.

Many generations of Tuchkovs worked in diplomatic and military service and contributed to strengthening the power of the Russian state. We meet the first news about the Tuchkovs during the time of Alexander Nevsky, when a particularly difficult situation developed for Rus': Mongol-Tatar khans fell from the east, and German knights and Swedish feudal lords from the north-west. In 1240, during the famous battle on the Neva with the Swedes, the Novgorod forces led by the brave 20-year-old Prince Alexander Yaroslavovich, nicknamed “Nevsky” for this battle. a certain Terenty, the son of Michael, fought in the ranks of the Russian army and fell in this battle. From him comes the Tuchkov family. Terenty's great-grandson Mikhail had two sons: Ignatius and Boris, nicknamed Tuchko-Morozov. All descendants of Boris Mikhailovich Tuchko-Morozov henceforth began to be called Tuchkovs.

At the end of the 18th century, a large estate located in two counties, Vereisky and Ruzsky, belonged to a comrade of the outstanding Russian commanders P.A. Rumyantsev and A.V. Suvorov, engineer-lieutenant general Alexei Vasilyevich Tuchkov, the Tuchkov estate was located in the village of Lyakhovo. The Tuchkovs owned Mukhino, Brykino (the village was burned to the ground by the Nazi invaders in 1941), Truteyevo and Artyukhino.

The sons of Boris Tuchko-Morozov, Ivan and Vasily Tuchkov, carried out major diplomatic assignments of Ivan III. One of them, Ivan, in 1477 negotiated with the Novgorodians about the annexation of Novgorod the Great to Moscow. In it

For a time, a strong army of the grand dukes stood under the walls of Novgorod, and the Novgorod boyars wanted to transfer Novgorod and all its rich possessions under the authority of the Polish-Lithuanian state.

Having learned about the intrigues of the Novgorod boyars, Ivan III in 1477 gathered a large army and made a campaign against Novgorod, sending Tuchkov to negotiate. Using the support of many supporters of Moscow, Tuchkov negotiated successfully and in 1478, Ivan III, during his last campaign, easily managed to capture Novgorod and finally annex it to Moscow.

In 1480, Vasily Borisovich Tuchkov conducted complex diplomatic affairs in negotiations between Ivan III and the brothers Boris Volotsky and Andrei Uglitsky. The appanage princes, dissatisfied with the growing power of the Grand Duke, rose up with their courts and an army numbering up to 20 thousand people and moved to the Lithuanian border. Ivan III sent Tuchkov to persuade his brothers not to start feudal unrest. In the face of the danger looming over Russia, in connection with the campaign of the Khan of the Golden Horde Akhmat and the increased requests of Moscow diplomats, the brothers decided to make peace with Ivan III and came to him with their troops on the river. Ugru. Seeing the presence of the united forces of the Russian princes, the Tatars did not dare to begin crossing the Ugra and went back to the Horde.

Thus, by reconciling Ivan III with his brothers, Boris Tuchkov contributed to the final fall of the Mongol-Tatar yoke in 1480. However, if you believe the letter of Ivan the Terrible to Andrei Kurbsky, who was the great-grandson of Vasily Tuchkov, the Tuchkovs, on the one hand, helped strengthen the power of the Grand Duke, and on the other, they opposed it. “You are accustomed,” the tsar says in the letter, “from your ancestors to commit treason: just as your grandfather Mikhailo Karamysh, with Prince Andrei Uglitsky, plotted treasonable customs against our grandfather, the Great Sovereign Ivan, so did your father, Prince Mikhailo with the Grand Duke Dmitry , the grandson of our father Vasily plotted many disastrous deaths; Also, your mother’s grandfather Vasily Tuchkov spoke many dirty and reproachful words to our grandfather, the great sovereign Ivan; “also your grandfather Mikhailo Tuchkov, at the death of our mother, the great Queen Elena, spoke many arrogant words to our clerk Tsyplyatyev.”

“You are accustomed,” the tsar says in the letter, “from your ancestors to commit treason: just as your grandfather Mikhailo Karamysh, with Prince Andrei Uglitsky, plotted treasonous customs against our grandfather, the Great Sovereign Ivan, so did your father, Prince Mikhailo with the Grand Duke Dmitry, the grandson of our father Vasily plotted many disastrous deaths; Also, your mother’s grandfather Vasily Tuchkov spoke many dirty and reproachful words to our grandfather, the great sovereign Ivan; Also, your grandfather Mikhailo Tuchkov, at the death of our mother, the great Queen Elena, spoke many arrogant words to our clerk Tsyplyatyev

This circumstance, however, did not prevent Vasily III from repeatedly sending Mikhail Tuchkov, who was reputed to be an independent person, as an ambassador to foreign lands to resolve complex diplomatic issues. Mikhail Tuchkov coped with these assignments brilliantly.

Carrying out complex diplomatic tasks in order to secure the southern borders of the Moscow state, Mikhail Tuchkov, with the rank of grand ducal ambassador, from 1512 to 1515 negotiated with the Crimean Khan Mengli-Girey. After the raids of the Crimean Tatars and the devastation of the Tula and Ryazan lands in 1512, Mikhail Tuchkov had to ensure that Mengli-Girey stopped his actions against Moscow in aid of the Polish king Sigismund.

Tuchkov completed his mission successfully. The Khan did not help his ally Sigismund during the war between Russia and Poland, the conquest of the Smolensk principality and part of the lands of Belarus in 1514, although Sigismund spared no money in bribing the Crimeans.

In 1516, having successfully completed negotiations with the Crimeans, Mikhail Tuchkov headed the Russian embassy in Kazan. This year, an embassy arrived from Kazan with the news that the Kazan khan Magmet-Amen was dangerously ill, and asked on behalf of the sick khan and all Kazan residents to release the captive Kazan prince Abdyl-Letif, who was imprisoned in Moscow, and to appoint him as khan in Kazan in the event of Aminieva’s death . The Moscow state was interested in having Moscow's protege rule in Kazan. Vasily III agreed to fulfill the requests of the Kazan people and sent an embassy to Kazan headed by Okolnichi Mikhail Tuchkov. Tuchkov took an oath from the khan and the entire land that Kazan would not appoint any ruler without the knowledge of the Grand Duke of Moscow, and as a result of these agreements, Letif was released, temporarily receiving Kashira to rule. The Russian government was especially concerned about the issue of preventing a representative of the house of Girey from reigning in Kazan.

Of the three sons of Mikhail Vasilyevich Tuchkov, Ivan and Vasily, as stated in the Tuchkov pedigree, were brave warriors; during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, they distinguished themselves in many battles, were governors in the annexation of the Volga region to the Russian state and in the protracted Livonian War. The grandchildren of his third son Mikhail, Ivan and David, also fought in the military field in the 17th century. The Tuchkovs, heroes of the Patriotic War of 1812, descend from their third brother Ermolai Stepanovich. The great-great-grandson of Ermolai Stepanovich Alexey Vasilyevich Tuchkov (1729-1799) was also involved in military affairs. His service took place during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which was waged by Russia against feudal Prussia. The Russian army defeated the drilled army of Frederick II and entered Berlin in 1760. A.V. Tuchkov was an ally of the talented Russian military leader Pyotr Aleksandrovich Rumyantsev and a contemporary of the great Russian commander Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov, who began his military career. Tuchkov, together with Rumyantsev, took part in the Russian-Turkish War of 1768-1774. Russian troops on the Danube won brilliant victories over the Turks. Tuchkov retired as an engineer-lieutenant general and later became a senator. All five sons of Lieutenant General Tuchkov became generals and four of them increased the glory of Russian weapons during the Patriotic War of 1812.

The fifth of the brothers, Alexey Alekseevich Tuchkov, who retired during the reign of Paul I in 1797, lived in Moscow for a long time, and then moved to the remote estate of Yakhontovo in the Penza province.

Pavel Alekseevich Tuchkov, or, as is commonly called, Tuchkov III, was born in 1776 in Vyborg in the family of engineer-major general Alexei Vasilyevich Tuchkov, who during this period commanded the fortresses located on the border of Russia with Sweden. The upbringing of young Tuchkov was affected by military life, since the Tuchkovs themselves came from a family of military people, whose life was most associated with military affairs. He received a family upbringing, then was brought up in a private boarding school with some German pastor, like all the children of Alexei Vasilyevich Tuchkov, he studied French - this was the fashion in Catherine’s times. Brought up on the ideas of the Great* French Revolution and the French encyclopedists, he was a humane and enlightened man.

According to family tradition, at the age of 9 Pavel Tuchkov was enlisted as a sergeant in the bombardment regiment, where his older brother, artillery captain Nikolai Tuchkov, was serving at that time. Two years later, eleven-year-old Tuchkov was promoted to ensign, and then ranks and awards rained down as if from a cornucopia. Having never participated in any battles by that time, in 1791 at the age of 15 he was promoted to captain and assigned to the second bombardier battalion. All these ranks and promotions through the ranks occurred thanks to the position of the father as lieutenant general of the engineering troops, a military comrade-in-arms of the outstanding commanders P. A. Rumyantsev and A. V. Suvorov.

In 1797, Tuchkov was promoted twice; he was first promoted to major, and by the end of the year to lieutenant colonel.

The last years of the 18th century were the period of the reign of Paul I, an unbalanced man, an extreme reactionary, a tyrant, whose word could lead to exile to a distant province or loss of service. Others, on the contrary, quickly rose in rank, especially those to whom the emperor once had to turn his favorable attention.

In 1797, Tuchkov was awarded the Order of St. Anna for the sword, and the following year, in 1798, during an inspection of the troops by Paul I in Moscow, he was transferred to the Guards artillery battalion, received the rank of colonel and with dizzying speed at the age of 25, without any special military merits, promoted to the rank of general with the appointment of chief of the first artillery regiment stationed in St. Petersburg.

But then the military career of Pavel Alekseevich Tuchkov suddenly ended. In November 1803 he was forced to ask to resign. At the beginning of his reign, Alexander I did not show his dislike for Pavel Tuchkov, but two years later this dislike of the new monarch became noticeable, and Tuchkov was not slow to resign. At this time, Pavel Alekseevich settled in his Lyakhov estate near Moscow and other villages, and paid attention to the estate, which was now the only source of income for the young retired general.

The new hostilities with Napoleonic France that began in 1806 and the increase in the contingent of troops forced Alexander I to turn to the military, to whom he clearly showed his reluctance, and Pavel Alekseevich Tuchkov was offered to re-enter military service. Having missed the usual military situation for three years of inactivity, P. A. Tuchkov gladly accepted the emperor’s offer and was appointed commander of the 10th brigade, which was newly formed in Tver of the 17th infantry division. The formation of the division was delayed and it did not have time to take part in hostilities. By this time, news arrived about the Peace of Tilsit, which was concluded by the French and Russian monarchs. A few days later, there in Tilsit, Napoleon made peace with Prussia. The brigade commanded by Tuchkov was taken to a camp near Vitebsk and remained there until December 1807. Then, as part of the entire 17th Infantry Division under the command of General A.I. Gorchakov, she set out for Finland, with which, as was said in the essay about N.A. Tuchkov, Russia started the war at the request of Napoleon, since Sweden did not join to the continental blockade of England, trying to maintain friendly relations with their old ally.

Tuchkov's brigade acted against the Swedes in southern Finland, advancing from Friedrichsgam to Sveaborg and Helsinki Force, forming the left column of the Russian army, which was tasked with clearing the northern coast of the Gulf of Finland from the Swedes. Here in Finland, during the war with the Swedes, General Tuchkov received his baptism of fire.

General A.I. Gorchakov, who led the left column, formed a detachment from the brigade of P.A. Tuchkov. Having given it the 30th and 31st Jaeger Regiments, a squadron of the Finnish Dragoon Regiment, 2 squadrons of the Grodno Hussar Regiment and a hundred Don Cossacks, he instructed the detachment to act on the right flank of the left column. Tuchkov's detachment successfully advanced along country roads following the Swedes, and on February 12, 1808, attacked a large Swedish detachment, putting it to flight on Abo.

In September 1808, the Swedes made an attempt to stop the Russian offensive by landing an amphibious assault. However, the Swedish landing force was thrown into the sea by Tuchkov’s detachment together with P.I. Bagration’s detachment that arrived here. At the same time, Tuchkov captured Gangut with 55 guns and, by order of the commander-in-chief of the Russian troops, General F. F. Buxgevden, brought the Gangut fortress into a state suitable for the defense of Russian troops.

P. A. Tuchkov received the task of organizing the defense of the Gulf of Finland from Sveaborg to Abo. At this time, he successfully supported the actions of the Russian rowing fleet, led by Captain 1st Rank Geigen, with fire from his batteries from the shore. Thanks to this, the Russian rowing fleet emerged victorious from a number of skirmishes with the Swedish fleet, repeating the exploits of Russian sailors led by Peter I, who defeated the Swedish fleet at Gangut in 1714.

Tuchkov successfully repelled Swedish attempts to carry out sabotage against Russian troops on the coast of the Gulf of Finland; he once eliminated a large Swedish detachment of Colonel Palen, who was trying to attack the headquarters of the commander-in-chief of the Russian army. Tuchkov's troops captured numerous Swedish detachments near the coast.

With the onset of cold weather and the cessation of Swedish attacks on Russian garrisons on the coast, in November 1808, Tuchkov’s brigade successfully operated as part of General Kamensky’s corps along the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia. The most important tasks were always entrusted to P. A. Tuchkov’s brigade.

In December 1808, the new Russian commander-in-chief, General B.F. Knorring, who replaced General F.F. Buxhoeveden in this post, received orders to invade Sweden, making a winter crossing through the Gulf of Bothnia. It was envisaged that the troops of General P.I. Bagration, concentrated in Abo, would occupy the Aland Islands with subsequent access to Swedish territory.

The brigade of P. A. Tuchkov now acted as part of the corps of P. I. Bagration and on March 5, moving along the hummocky ice, overcoming polynyas, Bagration’s troops occupied the Aland Islands, and the advance detachment of Ya. P. Kulnev on March 7 made a heroic transition across the ice of the Bothnian bay and captured the Swedish city of Grisselgam. The heroic actions of Major General Tuchkov in the war with Sweden were awarded the Order of St. Anne, 1st degree.

After the conclusion of the Friedrichsham Peace Treaty (September 1809), P. A. Tuchkov’s brigade was withdrawn to the 1st Zarad Army of General Barclay de Tolly, where it was caught in the Patriotic War of 1812, in which P. A. Tuchkov was included new heroic page.

In the Patriotic War of 1812, many residents of Ruza district were in the regular troops. The Tuchkov brothers made a particularly outstanding contribution to the defeat of Napoleonic army.

The Tuchkovs in Ruza district at that time owned the villages of Truteevo and Artyukhino, and in the neighboring Vereisky district they owned the villages of Mukhino, Lyakhovo, Brykino.

As part of the 1st Western Army, the 3rd Infantry Corps of Lieutenant General N.A. Tuchkov I fought back to the east. General Tuchkov's troops distinguished themselves in battles with the French vanguard near Vitebsk on July 14 (26), 1812. There, on July 15, a brigade consisting of the Revel and Murom regiments, part of N. A. Tuchkov’s corps, met the enemy in a rearguard battle. The brigade was commanded by his younger brother, Major General Alexander Tuchkov.

The brigade of A. A. Tuchkov, together with the Smolensk militia and other regular troops, took part in bloody battles at the Malakhovsky Gate of ancient Smolensk and held back the superior enemy troops from Davout’s corps for more than a day. However, it was dangerous to continue the defense of Smolensk. Napoleon, possessing a significant superiority in forces, could, having crossed the Dnieper, cause great harm to the Russian army by encirclement. On the evening of August 6 (18), Barclay de Tolly began to secretly withdraw his troops from near Smolensk.

Next, the 1st Western Army was divided into 2 columns. The first column, which included the 5th and 6th infantry, 2nd and 3rd cavalry corps with artillery and convoys under the command of General D.S. Dokhturov, departed from Smolensk along the ring road through the villages of Stabnya and Prudishchevo.

The second column, consisting of the 2nd, 3rd, 4th infantry and 1st cavalry corps under the command of Lieutenant General N.A. Tuchkov, was supposed to follow a shorter but more difficult road to the crossing, through the villages of Gorbunovo and Kataevo.

Ahead of the 2nd column was the vanguard under the command of Major General P. A. Tuchkov III. Both columns were ordered to unite at the Solovyova crossing by the evening of August 7 (19).

The second army also moved to the Solovyova crossing on the afternoon of August 6 (18). General P.I. Bagration left a strong detachment of General A.I. Gorchakov and a one and a half thousand Cossack detachment of A.A. Karpov near the village of Lubino. On August 7 (19), the 2nd Army crossed the Dnieper at the Solovyova crossing and stopped before reaching Dorogobuzh.

Napoleon, trying to cut off the retreat of the Russian troops and reach the crossing, blocking the retreat path of the Russian troops, sent Ney's corps, then the corps of Junot and Murat, to the village of Lubino and to the crossing. Meanwhile, the column of N. A. Tuchkov I was approaching the crossing, at the head of which were the regiments of the brigade of P. A. Tuchkov III.

In addition to these regiments, Lubin had only three Cossack regiments of A. A. Karpov. The three thousandth detachment of Tuchkov III, then increased by arriving reinforcements to 8 thousand infantry and cavalry, holding back the fierce attacks of Murat's cavalry and infantry. Ney, covered the retreat of the Russian armies to the Solovyova crossing. Detachment P. A. Tu�

The Tuchkovs owned lands in the Moscow, Tula, Vladimir, Simbirsk, and Yaroslavl provinces. In the Penza province they owned the village of Yakhontovo (Dolgorukovo) in Insarsky district (now Issinsky district).

Already in the 16th century, the Tuchkovs were close to the royal house, and in the 19th century, the family became famous in the War of 1812.

Alexey Vasilyevich Tuchkov (1729 - 1799, Moscow), engineer, lieutenant general, actual privy councilor. He took part in the Seven Years' War, managed an engineering and artillery unit in St. Petersburg, built a bridge on Vasilievsky Island, had 5 sons, including:

Alexey Alekseevich (1766 - 1853), retired major general since 1797, leader of the nobles of the Zvenigorod district of the Moscow province in 1812. For organizing the militia, Alexey Alekseevich was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd degree. He owned the village of Dolgorukovo and more than 1000 serfs, lived in Moscow and on the estate.

His son Alexey Alekseevich (December 26, 1800, Moscow - 1879, Dolgorukovo), retired lieutenant of the General Staff since 1826. He studied at the school of column leaders and at Moscow University, was a member of the Union of Welfare in 1818 and the Moscow Council of the Sevastopol Society in 1825. On December 14, 1825, Alexey Tuchkov was in Moscow, arrested in January 1826, spent 4 months in prison and was released due to lack of evidence. After retirement, he lived in the village of Dolgorukovo, and was elected leader of the nobility of the Insar district in 1832-1847. In 1847 he earned the Order of St. Vladimir, 4th degree, “as a reward for diligent and blameless service in the elections of the nobility.” And at the same time, in 1848-1850, as well as in 1853-1857, he was under the secret supervision of the police. In February 1850 he was arrested together with N.P. Ogarev, N.M. Satin, I.V. Selivanov for “belonging to a communist sect” according to the denunciation of Governor A.A. Panchulidzeva and L.Ya. Roslavlev, father of Ogarev’s first wife. Released after a month.

Tuchkov was a “good friend” of V.G. Belinsky, familiar with A.I. Herzen, who wrote: “An extremely interesting person, with an unusually developed practical mind.” Alexey Alekseevich was the guardian of minor I.A. Salov, future writer. He opened a sugar factory and a school for peasant children with 40 student places in Dolgorukovo, where he himself taught. Alexey Tuchkov was an ardent opponent of serfdom, was distinguished by his humane attitude towards peasants and repeatedly defended their interests before the authorities. In 1823, Alexey Alekseevich married Natalya Apollonovna Zhemchuzhnikova. They had two daughters:

Elena Alekseevna (1827 - 1871), wife of N.M. Satina, and

Natalya Alekseevna (1829 – 1913), memoirist, second wife of N.P. Ogarev, since 1857 - the common-law wife of A.I. Herzen.

Best of the day

Pavel Alekseevich (1803 - 1864), brother of Aleksey Alekseevich, uncle of Natalya Alekseevna Tuchkova-Ogareva, rose to the rank of lieutenant general, was a member of the State Council, Moscow Governor-General. After his death, two Tuchkov scholarships were established at Moscow University.

Review

Andrey Vyacheslavovich 24.09.2007 04:12:36

My ancestors rest in the cemetery in Kartino near the temple. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find the grave. According to my father, there was a large tombstone at the burial site. These were not poor people and helped with funds for the construction of the temple. Now I have purchased a dacha near Tuchkovo. In the ZhZL series there is an issue dedicated to the heroes of the war of 1812. There is a section dedicated to the Tuchkovs. I am very sorry that I missed this publication. I know little about our ancestors.

"You, whose wide greatcoats

Reminds me of sails

And whose eyes are like diamonds

They carved a mark on my heart,

Charming dandies of yesteryear."

Many people remember this piercingly inspired “Nastenka’s romance” from E. Ryazanov’s famous film “Say a word for the poor hussar.” Few people know who the author of his text is. Even less is known about who it was dedicated to.

The poem “To the Generals of the 12th Year,” several quatrains of which became the famous romance of A. Petrov, was written a century after the war of 1812 by the Russian poetess M. Tsvetaeva and dedicated to the 34-year-old major general, commander of Revelsky, who died heroically on the Borodino field infantry regiment to Alexander Tuchkov.

It’s easy to verify this - just read the full text of the poem to understand not only to whom it is addressed, but also the poet’s emotional attitude towards the addressee.

General A. Tuchkov

M. Tsvetaeva

“Oh, half erased in the engraving,

In one magnificent moment,

I met Tuchkov the fourth,

Your gentle face

And your fragile figure,

And golden orders...

And I, having kissed the engraving, did not know sleep.”

Tsvetaeva herself was poetically in love with the portrait-historical image of A. Tuchkov and kept a portrait image of the young hero general on her desk. And, apparently, it is no coincidence that M. Tsvetaeva more than once projected the knightly image of A. Tuchkov onto her husband S. Efron. In poems dedicated to Sergei, the courageous image of a knight-hero, very similar to Tuchkov, is always a red thread.

Who was this young general who captivated the poetic imagination of the famous poetess?

Alexander Alekseevich Tuchkov was born in 1778 in the family of an associate of the Field Marshal, Count P.A. Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky general engineer, head of all military fortresses on the Polish and Turkish borders, senator Alexei Vasilyevich Tuchkov, married to Elena Yakovlevna Kazarina.

Alexander was the youngest of five sons, and since all the brothers became very famous, renowned military men, in order to avoid confusion in the army they were called by numbers: Tuchkov 1, Tuchkov 2, etc.

The noble family of the Tuchkovs traced their origins to the Novgorod boyars resettled by Tsar John III from Novgorod to the outskirts of Moscow.

The Tuchkovs’ ancestor, Mikhail, came from Prussia, which is why he was called Prushanich. His son, Terenty Mikhailovich, was already a boyar under the Grand Duke Alexander Nevsky and participated in the famous Battle of Neva in 1240. One of his descendants received the nickname Tuchko - and this is how the famous noble family of the Tuchkovs appeared.

Since ancient times, the Tver branch of the Tuchkovs settled near Kalyazin in the village of Troitskoye, which has survived to this day. Here after his death in 1799. Aleksandr Tuchkova's mother, Elena Yakovlevna, lived with her husband, General Engineer Alexei Vasilyevich. Tuchkov preserved detailed records about the ownership of the patrimony of the village of Troitskoye in the Kashin Census Book (1628-1629) and the Kashin Census Book (1677).

Alexander Tuchkov himself was born in Kyiv, where his father was then serving. Having received an excellent education at home, the young man, according to family tradition, was assigned to serve in the army in the artillery unit.

Having the opportunity and a certain freedom of action, Alexander Tuchkov made a long trip around Europe, visiting the best academic institutions to expand his knowledge. There in Europe, long before the start of World War II, fate brought him together with Napoleon. In 1804, in Paris, he attended the solemn ceremony of proclaiming Napoleon Emperor of France.

After returning to Russia, Tuchkov takes command of the Murom Infantry Regiment and is sent to the battlefields of the Russian-Prussian-French War of 1806.

For personal courage and desperate bravery - this quality especially distinguished all the Tuchkov brothers - he was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, 4th degree, and appointed chief of the then famous Revel Infantry Regiment.

In a report on the actions of his subordinate Colonel A. Tuchkov, Count L.L. Bennigsen wrote: “Under the blows of a hail of bullets and grapeshot, he acted as if in a training exercise.”

Famous Russian writer, journalist, critic, publisher of the first half of the 19th century. F.V. Bulgarin, a former military officer in the French army, wrote about the military qualities of the Revel infantry regiment:

“I have never seen such excellent regiments as the Nizovsky and Revel infantry regiments... Not only Napoleon, but even Caesar did not have the best warriors!

The officers were great fellows and educated people; the soldiers went into battle as if they were going to a feast: together, cheerfully, with songs and jokes.”

F. Bulgarin (1789-1859)

Badge of the Revel Infantry Regiment

Then there was the Russian-Swedish War of 1808-1809, brilliant military operations under the command of M.B. Barclay de Tolly, rapid promotion (at the age of 31) to major general and honorary appointment as general on duty under the commander-in-chief, Governor General of Finland and Minister of War Barclay de Tolly.

The famous journalist of the 19th century, poet, public figure, hero of the Patriotic War of 1812, our fellow countryman Fyodor Glinka wrote about his friend A. Tuchkov:

“Have you seen, in the portrait, the young general, with the figure of Apollo, with extremely attractive facial features? There is intelligence in these features, but you don’t want to admire the mind alone when there is something external, something much more charming than the mind. There is soul in these features, especially on the lips and in the eyes! From these features one can guess that the person to whom they belong has (now already had!) a heart, has an imagination; He can dream and think even in a military uniform! Look how his beautiful head is ready to bow on his hand and indulge in a long, long series of thoughts!.. But in a lively conversation about the fate of the fatherland, a special life began to boil within him. And in the heat of the roaring battle, he left his European education, his quiet thoughts and walked along with the columns, and was, with a gun in his hands, in the epaulettes of a Russian general, a pure Russian soldier! This is General Tuchkov 4th.”

With the beginning of the Patriotic War, the commander of the Revel regiment A. Tuchkov as part of the division of Lieutenant General P.P. Konovnitsina fights back from the Russian border through Smolensk to a decisive place both in her life and in the history of the Fatherland - to a small village near Mozhaisk - Borodino.