Which of the following battles is called the Battle of Nations? Battle of the Nations near Leipzig

In the thousands of years of human history there have been a great many brilliant commanders and a huge number of major battles. Most of these battles are preserved in chronology only by the name of the area where they took place. Others, more large-scale, had, in addition to this, a sonorous name. The Battle of the Nations near Leipzig in 1813 is one of these. Among all the battles of the Napoleonic Wars era, this is the largest in terms of the number of countries participating in it. It was near Leipzig that another coalition of European powers made a new desperate attempt to stop the victorious march of the French army across the continent.

Background and prerequisites for the creation of the 6th coalition

The star of a talented commander originally from the island of Corsica lit up brightly during the French Revolution. It was the events in the country, as well as the intervention of European powers, that significantly facilitated Napoleon’s rapid advancement through the ranks. His landslide victories on the battlefield made him so popular among the citizens that he had no qualms about using his influence to interfere in the country's internal affairs. His role in decision-making on government issues increased. His tenure as first consul was short-lived and did not correspond to his ambitions. As a result, in 1804 he declared France an empire and himself emperor.

This state of affairs initially caused fear and anxiety among neighboring countries. Even during the Great French Revolution, anti-French coalitions were created. Basically, the initiators of their formation were 3 states - England, Austria and Russia. Each of the alliance member countries pursued its own goals. The first 2 coalitions, organized before Napoleon's coronation, fought with varying degrees of success. If during the period of the first coalition success accompanied the French army under the leadership of their future emperor, then during the existence of the second coalition of European empires the scales tipped in favor of the alliance. The main credit for the victories belonged to the Russian army under the leadership of the eminent commander A.V. Suvorov. The Italian campaign ended with a confident victory over the French. The Swiss campaign was less successful. The British and Austrians took credit for the Russian successes, supplementing them with territorial acquisitions. Such an ungrateful act caused discord between the allies. Russian Emperor Paul I responded to such an ugly gesture with a peace agreement with France and began to make plans against yesterday’s partners. However, Alexander I, who replaced him on the throne in 1801, returned Russia to the anti-French camp.

The III coalition began to form some time after the coronation of Napoleon and the declaration of France as an empire. Sweden and the Kingdom of Naples joined the union. The alliance members were extremely concerned about the aggressive plans of the Emperor of France. Therefore, this coalition was of a defensive nature. There was no talk of any territorial acquisitions during the fighting. The main emphasis was on the defense of their own borders. Starting from 1805 and ending in 1815, the confrontation with France was of a completely different nature, turning from anti-French into Napoleonic wars.

Unfortunately, the III coalition failed to achieve its goal. Austria was particularly hard hit. In October 1805, the French defeated the Austrians at Ulm, and a month later Napoleon solemnly entered Vienna. At the beginning of December, the “Battle of Three Emperors” took place at Austerlitz, which ended with the defeat of the Russian-Austrian army, which outnumbered its opponent. The Austrian sovereign Franz I personally arrived at Napoleon's headquarters to discuss the peace agreement signed in Presburg. Austria recognized the French conquests and was forced to pay indemnity. He also had to give up the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Under the patronage of Napoleon, the Rhine Confederation of German States was created. Only Prussia refused to submit and went over to the side of the coalition. Thus came the end of almost a thousand years of existence of the formal empire. The Allies were consoled by the defeat of the Franco-Spanish fleet by the British at Cape Trafalgar in October 1805. Napoleon had to say goodbye to the idea of conquering England.

Coalition V was actually a confrontation between France and Austria, which had returned to service, and was assisted by England. However, the war between the parties lasted no more than six months (from April to October 1809). The outcome of the confrontation was decided in the summer of 1809 at the Battle of Wagram, which ended with the defeat of the Austrians, further retreat, and then the signing of the Schönbrunn Agreement.

Thus, none of the coalitions was able to achieve success in the battles against Napoleon's army. Each time, the Emperor of France made tactically correct decisions and gained the upper hand over the enemy. The only rival preventing Bonaparte's dominance was England. It seemed that the French army was invincible. However, this myth was destroyed in 1812. Russia, not agreeing with the blockade of England, began to follow the terms of the Tilsit Peace less and less. Relations between the Russian Empire and France gradually cooled until they escalated into war. On the side of the French army were the Austrians and Prussians, who were promised some territorial gains if the campaign was successful. Napoleon's campaign with an army of almost half a million began in June 1812. Having lost most of his soldiers in the Battle of Borodino, he began a hasty retreat back home. Bonaparte's campaign in Russia ended in complete fiasco. Almost all of his huge army was killed both in battles with the enemy and during a hasty retreat, finished off by partisan detachments. The myth of the invincibility of the French army was dispelled.

Preparing the parties for war. VI coalition

Russia's success in the war with France instilled confidence in its allies in the final victory over Bonaparte. Alexander I did not intend to rest on his laurels. Simply expelling the enemy from the territory of his state was not enough for him. He intended to fight until the enemy was completely defeated on his territory. The Russian emperor wanted to lead the Sixth Coalition in the new war.

Napoleon Bonaparte also did not sit idle. Having reached Paris with the handful that remained of his large army in the second half of December 1812, he literally immediately issued a decree on general mobilization. The number of conscripts collected from all over the empire was 140 thousand people, another 100 thousand were transferred from the National Guard to the regular army. Several thousand soldiers returned from Spain. Thus, the total number of the new army was almost 300 thousand people. The Emperor of France sent part of the newly assembled armada to his stepson Eugene Beauharnais in April 1813 to contain the united Russian-Prussian army at the Elbe. The war of the Sixth Coalition with Napoleon was already inevitable.

As for the Prussians, King Frederick William III did not initially intend to go to war against France. But the change in decision was facilitated by the advance of the Russian army in East Prussia and the friendly offer of Alexander I to join the fight against the common enemy. The chance to get even with the French for past defeats could not be missed. Frederick William III went to Silesia, where by the end of January 1813 he managed to gather more than a hundred thousand soldiers.

Meanwhile, having occupied Poland, the Russian army under the command of the hero of the Battle of Borodino, Kutuzov, headed to Capish, where in mid-February it defeated a small Saxon army led by Rainier. It was here that the Russians later camped, and at the end of the month a cooperation agreement was signed with the Prussians. And at the end of March, Frederick William III officially declared war on France. By mid-March, Berlin and Dresden were liberated. All of central Germany was occupied by the Russian-Prussian army. In early April, the Allies captured Leipzig.

However, this is where the success ended. The new commander of the Russian army, General Wittgenstein, acted extremely unconvincingly. At the beginning of May, Napoleon's army went on the offensive and won the general battle of Lützen. Dresden and all of Saxony were again occupied by the French. At the end of the month, another major battle took place at Bautzen, in which the French army again celebrated Victoria. However, both victories were given to Napoleon at the cost of losses that were 2 times higher than the losses of the allies. The new commander of the Russian army, Barclay de Tolly, unlike his predecessor, did not seek to engage in battle with the enemy, preferring a retreat alternating with minor skirmishes. Such tactics bore fruit. Exhausted by constant movements and losses, the French army needed a pause. Moreover, cases of desertion have become more frequent. At the beginning of June, the parties in Poischwitz signed a short-term truce. This treaty played into the hands of the allies. By mid-June, Sweden had joined the coalition, and England promised financial assistance. Austria initially acted as a mediator in the upcoming peace negotiations. However, Napoleon was not going to lose, much less share, the captured territories. Therefore, Emperor Francis II accepted the Trachenberg Plan of the Allies. On August 12, Austria moved to the coalition camp. The end of August passed with varying degrees of success for both sides, but Napoleon’s army was significantly thinned out both from losses in battles, as well as from illness and desertion. September passed calmly, there were no major battles. Both camps were pulling up reserves and preparing for the decisive battle.

Disposition of forces before battle

In early October, the Russians unexpectedly attacked and captured Westphalia, where Napoleon's younger brother Jerome was king. Bavaria, taking advantage of the opportunity, defected to the Allied camp. The situation became tense. A major battle seemed inevitable.

By the beginning of Battle VI, the coalition, according to various sources, managed to assemble an army of almost a million, along with numerous reserves. This entire huge armada was divided into several armies:

- Bohemian was led by Schwarzenberg.

- The Silesian army was commanded by Blücher.

- The heir to the Swedish throne, Bernadotte, was at the head of the Northern Army.

- The Polish army was led by Bennigsen.

About 300 thousand people with 1,400 guns gathered on the plain near Leipzig. Prince Schwarzenberg was appointed commander-in-chief of the coalition forces, carrying out the orders of the three monarchs. They planned to encircle and destroy Napoleon's army. The army of the Emperor of France and her allies was 1.5 times inferior in numbers and 2 times inferior in firepower to their opponent. His army included some German states of the Rhineland, Poles and Danes. Bonaparte planned to give battle to the Bohemian and Silesian armies even before the arrival of the remaining units. The fate of Europe was to be decided in Leipzig.

First day of battle

Early in the morning of October 16, 1813, the opponents met on a plain near the city. This day is considered the official date of the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig. At 7 o'clock the coalition forces were the first to attack. Their goal was the village of Wachau. However, Napoleon's divisions in this direction managed to push the enemy back. Meanwhile, part of the Bohemian army attempted to cross to the opposite bank of the Place River to attack the left wing of the French army, but was driven back by heavy artillery fire. Until noon, the parties were unable to move forward even a meter. In the afternoon, Napoleon prepared a plan to break through the weakened center of the coalition army. Carefully camouflaged French artillery (160 guns), led by A. Drouot, opened heavy fire on the enemy’s most vulnerable zone. By 15 o'clock in the afternoon, infantry and cavalry under the leadership of Murat entered the battle. They were opposed by the Prussian-Russian army under the command of the Prince of Württenberg, which was already weakened by the artillery of General Drouot. The French cavalry, with the help of infantry, easily broke through the center of the allied army. The road to the camp of the three monarchs was open; only a measly 800 meters remained. Napoleon was preparing to celebrate his victory. However, the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig could not end so easily and quickly. Russian Emperor Alexander I expected such a move from the enemy and therefore at an important moment he ordered the Russian-Prussian reserve forces of Sukhozanet and Raevsky, as well as Kleist’s detachment, to cross the French. From his camp on a hill near Thonberg, Napoleon watched the progress of the battle and, realizing that the coalition had practically taken away his victory, sent cavalry and infantry to that very hot spot. Bonaparte was going to decide the outcome of the battle before the arrival of the reserve armies of Bernadotte and Bennigsen. But the Austrians sent their forces to meet his aid. Then Napoleon sent his reserve to his ally, the Polish prince Poniatowski, who was being pressed by the division of the Austrian Merveld. As a result, the latter were thrown back, and the Austrian general was captured. At the same time, on the opposite side, Blucher fought with the 24,000-strong army of Marshal Marmont. But the Prussians, led by Horn, showed real courage. To the beat of drums, they went into a bayonet battle against the French and drove them back. The villages of Mekern and Viderich alone were captured several times by one side or the other. Day one of the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig ended in a combat draw with heavy losses for both the coalition (about 40 thousand people) and Napoleon's army (about 30 thousand soldiers and officers). Closer to the morning of the next day, the reserve armies of Bernadotte and Bennigsen arrived. Only 15,000 people joined the Emperor of France. The 2-fold numerical superiority gave the allies an advantage for further attacks.

Second day

On October 17, no battles took place. The parties were busy healing wounds and burying the dead. Napoleon understood that with the arrival of coalition reserves it would be almost impossible to win the battle. Taking advantage of the inaction in the enemy camp, he asked Merveld, who was captured by him, to return to the allies and convey that Bonaparte was ready to conclude a truce. The captured general left on an errand. However, Napoleon did not wait for an answer. And this meant only one thing - a battle was inevitable.

Day three. Turning point in the battle

Even at night, the Emperor of France gave the order to pull all army units closer to the city. Early in the morning of October 18, coalition forces launched an attack. Despite the clear superiority in manpower and artillery, the French army skillfully held back the enemy's onslaught. There were battles literally for every meter. Strategically important points moved first to one, then to another. Langeron's Russian division fought on the left wing of Napoleon's army, trying to capture the village of Shelfeld. The first two attempts were unsuccessful. However, the third time the count led his forces into a bayonet battle and with great difficulty captured the strong point, but Marmont's reserves again drove the enemy back. An equally fierce battle took place near the village of Probstade (Probstgate), where the center of the French army was located. The forces of Kleist and Gorchakov entered the village by noon and began storming the houses where the enemies were located. Napoleon decided to use his main trump card - the famous Old Guard, which he personally led into battle. The opponent was thrown back. The French launched an attack on the Austrians. The ranks of the coalition forces began to burst at the seams. However, at the decisive moment something unexpected happened that changed the entire course of the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig. The Saxons betrayed Napoleon in full force, turned around and opened fire on the French. This act gave an advantage to the allies. It became more and more difficult for Bonaparte to hold the positions of the army. The Emperor of France knew that he could not withstand another powerful attack. At night the French began to retreat. The army began crossing the Elster River.

Day four. Final victory

On the morning of October 19, coalition troops saw that the enemy had cleared the plain and was hastily retreating. The Allies began to storm the city, in which the units of Poniatowski and Macdonald were located, covering the retreat of Napoleon's army. Only by noon was it possible to take possession of the city, knocking out the enemy from there. In the confusion, someone accidentally set fire to the bridge over Elster, through which all the French forces had not yet managed to cross. Almost 30,000 people remained on this side of the river. Panic began, the soldiers stopped listening to their commanders and tried to cross the river by swimming. Others died from enemy bullets. Poniatowski's attempt to rally the remaining forces failed. Twice wounded, he rushed with his horse into the river, where he met his death. The French soldiers remaining on the shore and in the city were destroyed by the enemy. The Battle of the Nations near Leipzig ended in a landslide victory.

The meaning of the battle for the parties

Briefly, the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig can be interpreted as the greatest event of the first half of the 19th century. For the first time in the long history of the Napoleonic wars, a turning point came in favor of the Allies. After all, the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig in 1813 is the first major victory over the enemy and, in fact, revenge for the shameful defeat at Austerlitz in 1805. Now regarding the losses on both sides. The results of the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig can be considered disappointing. The Allies lost 60,000 people killed, Napoleon - 65,000. The cost of victory over the French was high, but these sacrifices were not in vain.

Events after the battle

Napoleon was given a rather offensive slap in the face at the Battle of Leipzig. Returning to Paris in November 1813, he gathered his strength and decided to hunt down and destroy the enemy armies one by one. An army of 25,000 remained in the capital under the command of Marshals Marmont and Mortier. The emperor himself, with almost 100 thousand troops, went to Germany and then to Spain. Until March 1814, he managed to win several impressive victories and even persuade the coalition forces to sign a peace agreement, but then they acted in a completely different way. Leaving Napoleon to fight with his insignificant units far from France, the Allies sent an army of 100,000 to Paris. At the end of March, they defeated the troops of Marshals Marmont and Mortier and took control of the country's capital. Bonaparte returned too late. On March 30, Napoleon signed a decree abdicating power, and then he was exiled to Elba. True, he didn't stay there long...

The Battle of Nations in the Memory of Descendants

The Battle of Leipzig became a fateful event of the 19th century and, naturally, was not forgotten by future generations. Thus, in 1913, the national monument to the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig was built. The Russians living in the city also did not forget about the descendants who took part in the battle. An Orthodox memorial church was consecrated in their memory. Also, in honor of the centenary of the victory, coins with a memorable date were minted.

For four days, from October 16 to 19, 1813, a grandiose battle, later called the Battle of the Nations, unfolded on a field near Leipzig. It was at that moment that the fate of the empire of the great Corsican Napoleon Bonaparte, who had just returned from an unsuccessful eastern campaign, was being decided.

If the Guinness Book of Records existed 200 years ago, the peoples of Leipzig would have been included in it according to four indicators at once: as the most massive battle, the longest in time, the most multinational and the most overloaded with monarchs. The last three indicators, by the way, have not yet been beaten.

Fateful decision

The catastrophic results of the 1812 campaign did not yet mean the collapse of the Napoleonic empire. Having placed young conscripts under arms early and assembled a new army, Bonaparte in the spring of 1813 launched a series of counterattacks on the Russians and their allies, restoring control over most of Germany.However, by concluding the Pleswitz Truce, he lost time, and after its end, the anti-Napoleonic coalition was replenished with Austria and Sweden. In Germany, Bonaparte's strongest ally remained Saxony, whose king, Frederick Augustus I, was also the ruler of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw recreated on the ruins of Poland.

To protect the Saxon capital of Dresden, the French emperor allocated the corps of Marshal Saint-Cyr, he sent the corps of Marshal Oudinot to Berlin, and MacDonald's corps moved east to protect himself from the Prussians. This dispersion of forces was alarming. Marshal Marmont expressed the fear that on the day Napoleon won one major battle, the French would lose two. And I was not mistaken.

On August 23, the Allied Northern Army defeated Oudinot at Grosberen, and on September 6 defeated Ney, who replaced him, at Dennewitz. On August 26, Blücher's Silesian army defeated Macdonald at Katzbach. True, Napoleon himself on August 27 defeated the main Bohemian army of Prince Schwarzenberg, which inadvertently approached Dresden. But on August 30, the retreating Bohemian army at Kulm smashed Vandam’s corps that turned up under its feet. The Allied command decided to refrain from fighting Napoleon himself, but to destroy large formations that had separated from his main forces. When this strategy began to produce results, Napoleon decided that he should impose a general battle on the enemy at any cost.

Executing bizarre pirouettes of maneuvers and counter-maneuvers, Bonaparte and the Allied armies from different sides were approaching the point where the fate of the campaign was to be decided. And this point was the second largest city in Saxony, Leipzig.

Two steps away from victory

Having concentrated his main forces south and east of Dresden, Bonaparte hoped to attack the enemy’s right flank. His troops stretched along the Plaise River. Bertrand's corps (12 thousand) stood at Lindenau in case the so-called Polish Army of Bennigsen appeared from the west. The troops of Marshals Marmont and Ney (50 thousand) were responsible for the defense of Leipzig itself and were supposed to repel Blucher’s offensive in the north.

On October 16, already at 8 o’clock in the morning, the Russian corps of Eugene of Württemberg attacked the French at Wachau, which ruined Napoleon’s entire plan. Instead of the destruction of the Allied right flank, the fiercest fighting broke out in the center. At the same time, the Austrian corps of Giulai became more active in the north-west, completely absorbing the attention of Marmont and Ney.

At about 11 o'clock Napoleon had to throw into battle the entire young guard and one division of the old one. For a moment, it seemed that he managed to turn the tide. A “large battery” of 160 guns brought down on the Allied center “a barrage of artillery fire unheard of in the history of wars in its concentration,” as Russian general Ivan Dibich wrote about it.

Then 10 thousand of Murat’s cavalry rushed into battle. At Meisdorf, his horsemen rushed to the very foot of the hill, on which was the headquarters of the allies, including two emperors (Russian and Austrian) and the King of Prussia. But even those still had “trump cards” in their hands.

Alexander I, having calmed his fellow crown-bearers, advanced the 100-gun battery of Sukhozanet, Raevsky’s corps, Kleist’s brigade and the Life Cossacks of his personal convoy to the threatened area. Napoleon, in turn, decided to use the entire Old Guard, but his attention was diverted by the attack of Merfeld's Austrian corps on the right flank. That’s where the “old grumps” went. They crushed the Austrians and even captured Merfeld himself. But time was lost.

October 17 was a day of reflection for Napoleon, and unpleasant reflections at that. In the north, the Silesian army captured two villages and was clearly going to play the role of a “hammer” the next day, which, having fallen on the French, would crush them to the “anvil” of the Bohemian army. What was even worse was that by the 18th the Northern and Polish armies were supposed to arrive on the battlefield. Bonaparte could only retreat to a sealed retreat, leading his troops through Leipzig and then transporting them across the Elster River. But he needed another day to organize such a maneuver.

Betrayal and fatal mistake

On October 18, with the forces of all four of their armies, the Allies hoped to launch six coordinated attacks and encircle Napoleon in Leipzig itself. It didn't all start out very smoothly. The commander of the Polish units of Napoleonic army, Józef Poniatowski, successfully held the line along the Plaise River. Blücher was essentially marking time, not receiving timely support from Bernadotte, who was taking care of his Swedes.Everything changed with the advent of Bennigsen's Polish Army. Paskevich’s 26th Division, which was part of it, initially formed a reserve, ceding the right of the first attack to Klenau’s Austrian corps. Paskevich subsequently spoke very sarcastically about the actions of the allies. First, the Austrians marched past his troops in even ranks, with their officers shouting to the Russians something like: “We will show you how to fight.” However, after several grape shots, they turned back and again returned in orderly ranks. “We carried out an attack,” they said proudly, and they no longer wanted to go into the fire.

The appearance of Bernadotte was the final point. Immediately after this, the Saxon division, Württemberg cavalry and Baden infantry went over to the Allied side. In the figurative expression of Dmitry Merezhkovsky, “a terrible emptiness gaped in the center of the French army, as if the heart had been torn out of it.” This is said too strongly, since the total number of defectors could hardly exceed 5-7 thousand, but Bonaparte really had nothing to bridge the gaps that had formed.

Early on the morning of October 19, Napoleon's units began to retreat through Leipzig to the only bridge over the Elster. Most of the troops had already crossed when, around one o'clock in the afternoon, the mined bridge suddenly blew up. The 30,000-strong French rearguard had to either die or surrender.

The reason for the premature explosion of the bridge was the excessive timidity of the French sappers, who heard the heroic “hurray!” soldiers of that same Paskevich division burst into Leipzig. Subsequently, he complained: they say that the next night “the soldiers did not let us sleep, they pulled the French out of Elster shouting: “They caught a big sturgeon.” These were drowned officers on whom money, watches, etc. were found.”

Napoleon with the remnants of his troops retreated to French territory in order to continue and finally lose the fight the following year, which was no longer possible to win.

"Battle of the Nations". Battle of Leipzig 1813

The summer truce of 1813 was ending. The Austrian Foreign Minister Metternich failed to convince Napoleon to make peace on terms that were honorable to him. For this reason, on August 11, Austria and Sweden declare war on France and join the Russian-Prussian coalition in order to force Napoleon to think about peace on the battlefields.

The French emperor thought completely differently; he believed in his lucky star. After all, after the disastrous campaign in Russia and the loss of his “Great Army,” he managed to quickly assemble a new army of two hundred thousand and in May 1813 win a number of victories. And when Metternich, who had inspired the truce, came with peace proposals, Napoleon did not want to hear about any concessions, believing that having made concessions once, the allies would demand them in the future, considering this a sign of weakness, although most of his marshals the generals considered the conditions quite acceptable. But as it happened, the anti-French coalition grew and Napoleon began planning an autumn campaign. The main problem was the replenishment of recruits. Most of the warriors who gained glory with him died on the battlefields or in the endless snow-covered expanses of Russia, and recalling those who remained from Spain or from numerous garrisons throughout Europe means weakening the empire. We had to call up 18, 19 year old boys for the next drafts. But even this did not stop Napoleon.

The Allies had no problems with conscription, as well as with equipping them with weapons and artillery. They had another problem, the lack of a commander capable of competing with Napoleon. The former marshal of Napoleon, and now the heir to the Swedish throne, Bernadotte, advised the allied sovereigns to call on General Moreau, who was in America. He was a talented commander who commanded the French Republican troops after the revolution and had a reputation among them almost comparable to that of Bonaparte. In 1804 he was accused of participating in a conspiracy against Napoleon and expelled, going into exile on the American continent. From then on, the emperor became his mortal enemy. In August, Moreau arrived at the Allied location.

So the truce is over. Napoleon attacks the allied forces near Dresden on August 27 and inflicts a decisive defeat on them. The roar of artillery from 1200 guns on both sides echoed incessantly over the battlefield. General Moreau, the commander of the allied forces, together with Emperor Alexander and a group of horsemen, was on a hillock when a cannonball fired at this group crushed the general’s legs. A few days later he died. Having suffered heavy losses, the allies retreated along several roads towards the Ore Mountains, pursued by French marshals and generals. One of them, General Vandamm, greatly carried away by the pursuit, broke away from the main forces and on August 30 was defeated and captured, with the remnants of his corps, in the Battle of Kulm. This inspired the allies, especially since things were moving better in other areas. Marshal Oudinot at Gossberen, Marshal MacDonald on the Katzbach River, and even Marshal Ney himself at Dennewitz, where the Saxons let him down, suffered sensitive defeats.

The middle and end of September passed relatively calmly. But in October the active phase resumed, the warring armies maneuvered, attacking each other. By October 15, the parties settled down on the plain in the Leipzig region, Napoleon decided to give a general battle. It was here that the fate of the campaign was to be decided. On October 16, the morning attack of the Allies began the greatest battle, in which more than half a million people participated on both sides, called the “Battle of the Nations.” Napoleon's army consisted of the French, Italians, Poles, Saxons and Dutch; they were opposed by the Russians, Austrians, Prussians and Swedes. At the head of the corps and armies of the opposing sides were such prominent military leaders as the King of Naples, the outstanding cavalryman I. Murat, the “bravest of the brave” Marshal M. Ney, Marshals Victor, Marmont and MacDonald, and Yu. Poniatovsky, the Austrian field marshal who had just received the marshal’s baton Prince K. Schwarzenberg, Prussian Field Marshal G. Blucher, Russian generals M. B. Barclay de Tolly and L. L. Bennigsen.

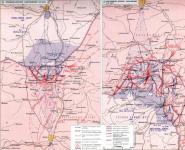

On the morning of October 16, the arrangement of the parties looked as follows. Napoleon's army was located near Leipzig in a semicircle. The emperor himself with the main forces, approximately 110 thousand people, settled down south of the city. His positions extended along the line: Connewitz, Markkleeberg, Wachau, Lieberwolkwitz, Holzhausen. Napoleon chose the vicinity of Wachau as his location. He was opposed by the Bohemian army of Prince Schwarzenberg, divided into two wings. The left wing, about 35 thousand Austrians, was commanded by the Prince of Hesse-Homburg. The right, main one, about 50 thousand consisting of the Austrians of Klenau, the Russians of Wittgenstein and the Prussians of Kleist, was commanded by General of the Infantry M.B. Barclay de Tolly. In addition, the Bohemian Army expected the approach of the Russian Polish Army of General L. L. Bennigsen and the Austrian Corps of Colloredo, located 60 miles away.

West of Leipzig, near Lindenau, Napoleon sent Bertrand's 20,000-strong corps to guard the only possible route of retreat, opposite which was stationed an equal-sized Austrian detachment of General Gyulay.

Finally, in the north, Marshals Ney and Marmont with 45 thousand people confronted the Silesian 60 thousand Russian-Prussian army of Field Marshal Blucher. In addition, Blucher's army was awaiting the arrival of the Northern Russian-Prussian-Swedish army of Prince Bernadotte, in the amount of 55 thousand people, located 40 miles away. It must be said that one of Napoleon’s mistakes in this battle was underestimating the Silesian army. During the battle, the emperor ordered Marmont's corps to move to the south, thereby weakening the northern flank, which was already inferior to the allies. But the order was never executed.

As for artillery, on October 16 the Allies had about 1,000 guns, and with the approach of Bernadotte and Bennigsen to the battlefield, there were up to 1,400 guns. The French army had up to 700 guns.

At 8 a.m. on August 16, after artillery barrage, Barclay's troops launched a frontal attack on the French. At 9.30 his left flank saw its first success; Kleist, having thrown Poniatowski away, occupied Markkleeberg. Augereau comes to the rescue and knocks out the Russians and Prussians Four times the city changes hands and remains with the French. In the center, Prince Eugene of Württemberg pushes back Marshal Victor and breaks into Wachau, bringing up artillery. Napoleon, having assembled a 100-gun battery here, begins an artillery duel. Having suffered heavy losses, Prince Eugene was forced to leave Wachau and retreat. On the right, at 9 am, Prince Gorchakov, and a little later Klenau, engage in battle with the corps of MacDonald and Lauriston for Lieberwolkwitz and take it, but at 11 o’clock, after the approach of French reserves and the withdrawal of Prince Eugene, fearing an attack on the exposed left flank, they leave it. As for the left wing of the Bohemian army, after the unsuccessful attack by Connewitz, the Prince of Hesse-Homburg received orders from Schwarzenberg to send his troops to reinforce Barclay. By noon, the offensive of the Bohemian army ran out of steam and it was driven back along the entire front, suffering huge losses. Seeing this, Napoleon began to prepare a counteroffensive. He ordered General Drouot to conduct artillery preparation. 160 guns opened fire with terrifying power, causing the earth to tremble. At 3 o'clock Murat's famous cavalry attack on the center of the Bohemian army begins. 10 thousand heavy cavalry break through the center and approach closely to the Wachberg hill, where the headquarters of the allied monarchs was located. Emperor Alexander orders Orlov-Denisov to counterattack the French horsemen. The fearless attack of the Life Cossack Regiment allows the 100 cannon battery of General Sukhozanet to be brought up, which with heavy fire, with the support of the grenadiers of General N.N. Raevsky, led to confusion and the withdrawal of Murat's cavalry. By nightfall the fighting had subsided. The first day in the southern theater of the battle ended with Napoleon's slight advantage.

In the western sector, General Gyulay unsuccessfully attacked Bertrand's corps. But in the north of Leipzig, Blucher's Silesian army achieved significant successes. And if Wiederitz could not be captured due to the heroic defense of Dombrowski’s Poles, then Meckern, attacked by the Prussians of York, was captured. Marmont's corps, which, on Napoleon's orders, had moved towards him near Wachau, returned and was completely defeated. The front was broken through.

On October 17, no active operations were carried out, except for the further advance of Blucher, where he closely approached Leipzig from the north. The parties took care of the dead and wounded and prepared for a new battle. On this day, to the joy of the allies, Bernadotte's Northern Army and Bennigsen's Polish Army approached them. The strategic initiative passed to the coalition troops. Napoleon began to understand this very well, pulling his forces closer to Leipzig, because it was no longer possible to hold the extended front.

On the morning of October 18, the battle resumed with renewed vigor. The Bohemian army launched an attack in a dense wall. The left wing of the Prince of Hesse-Homburg, wounded and replaced by Field Marshal Colloredo, pushed the French back to Connewitz, but Marshal Oudinot with two divisions and the Young Guard drove back the attackers. To the right, Barclay tried to take possession of Probstheida, but was counterattacked by Marshal Victor and the Old Guard, who, in turn, were also stopped by Allied artillery. And success came in the sector of Bennigsen’s Polish Army, which was located to the northeast and adjacent to Barclay’s Left Wing. Having launched an offensive at 2 o'clock, Bennigsen's army, together with Bernadotte's army and the Russian corps of Lanzheron and Saken, attached to them from the Silesian army, captured Holzhausen and Paunsdorf with a decisive attack. This is where the key moment of the battle took place. The Saxon corps, as well as the Baden and Württembergers, who were part of Napoleon’s army, ceased fire and went over to the side of the allies; by the evening, a huge gap had formed in the front of Napoleon’s army. The Emperor gives the order to prepare for retreat.

Early in the morning of October 19, convoys, artillery, cavalry, the corps of Victor and Augereau, Napoleon with the Old and Young Guards began crossing the bridge over the Elster River in Leipzig. The retreat of the corps of Ney, MacDonald, Lauriston and Poniatowski's Poles covered the retreat. At 10 am the assault on Leipzig began. Allied armies entered the city from several sides. Having let Ney's corps cross the crossing, the engineer non-commissioned officer, who was in charge of it during the senior officer's absence, heard very close shots and blew up the bridge ahead of time. 20 thousand French troops were cut off. Macdonald was able to swim across the river, Poniatowski found his death in it, and Lauriston and Rainier were captured. The total losses of Napoleon's army during the “Battle of the Nations” amounted to almost 80 thousand killed, wounded and prisoners. 325 guns went to the winners. The Allies lost up to 55 thousand killed and wounded, of which 23 thousand were Russian.

Thus ended the largest battle of the 19th century. Napoleon with the remnants of his army retreated to France to now wage only a defensive war. There were only a few months left until the end of the era, the era of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

After the defeat in Russia and return to Paris, Napoleon developed vigorous activity to create a new army. It must be said that this was his peculiarity - during a crisis situation, Napoleon awakened enormous energy and efficiency. The Napoleon of the “model” of 1813 seemed better and younger than the emperor of 1811. In his letters sent to his allies, the monarchs of the Confederation of the Rhine, he reported that Russian reports should not be trusted; Of course, the Grand Army suffered losses, but remains a powerful force of 200 thousand soldiers. In addition, the empire has another 300 thousand soldiers in Spain. Nevertheless, he asked the allies to take measures to increase their troops.

In reality, in January Napoleon already knew that the Grand Army was no more. The chief of staff, Marshal Berthier, told him briefly and clearly: “The army no longer exists.” Of the half a million people who marched across the Neman six months ago, few returned. However, Napoleon was able to form a new army in just a few weeks: by the beginning of 1813, he gathered 500 thousand soldiers under his banner. True, France was depopulated; they took not only men, but also young men. On April 15, the French emperor went to the location of the troops. In the spring of 1813 there was still an opportunity to make peace. The Austrian diplomat Metternich persistently offered his mediation in achieving peace. And peace, in principle, was possible. Petersburg, Vienna and Berlin were ready for negotiations. However, Napoleon makes another fatal mistake - he does not want to make concessions. Still confident in his talent and the power of the French army, the emperor was convinced of victory. Napoleon hoped for a brilliant revenge already on the fields of Central Europe. He has not yet realized that defeat in Russia is the end of his dream of a pan-European empire. The terrible blow struck in Russia was heard in Sweden, Germany, Austria, Italy and Spain. In fact, a turning point came in European politics - Napoleon was forced to fight with most of Europe. The armies of the sixth anti-French coalition opposed him. His defeat was a foregone conclusion.

Initially, Napoleon still won victories. The authority of his name and the French army was so great that the commanders of the sixth coalition lost even those battles that could have been won. On April 16 (28), 1813, death overtook the great Russian commander, hero of the Patriotic War of 1812, Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov. He actually died in combat. The whole country mourned his death. Pyotr Christianovich Wittgenstein was appointed to the post of commander-in-chief of the Russian army. On May 2, 1813, the Battle of Lützen took place. Wittgenstein, initially having a numerical advantage over Ney's corps, acted indecisively. As a result, he dragged out the battle, and Napoleon was able to quickly concentrate his forces and launch a counteroffensive. The Russian-Prussian troops were defeated and were forced to retreat. Napoleon's forces reoccupied all of Saxony. On May 20-21, 1813, at the Battle of Bautzen, Wittgenstein's army was again defeated. The superiority of Napoleon's military genius over Wittgenstein was undeniable. At the same time, his army suffered greater losses in both battles than Russian and Prussian troops. On May 25, Alexander I replaced Commander-in-Chief P. Wittgenstein with the more experienced and senior Michael Barclay de Tolly. Napoleon entered Breslau. The Allies were forced to offer a truce. Napoleon's army also needed rest, the supply of the French troops was unsatisfactory, and he willingly agreed to a ceasefire. On June 4, a truce was concluded.

The war resumed on August 11, but with a significant superiority in strength among the allies, who were joined by Austria and Sweden (they were promised Danish Norway). In addition, in mid-June London pledged to support Russia and Prussia with significant subsidies to continue the war. The commander-in-chief of the allied armies was the Austrian field marshal Karl Schwarzenberg. On August 14-15 (26-27), 1813, the battle of Dresden took place. Schwarzenberg's Bohemian army had a numerical advantage, he had significant reserves, but showed indecision, allowing Napoleon to seize the initiative. The two-day battle ended in heavy defeat for the allied forces, who lost 20-28 thousand people. The Austrian army suffered the greatest losses. The Allies were forced to retreat to the Ore Mountains. True, during the retreat, the allied forces destroyed the French corps of Vandam in the battle of August 29-30 near Kulm.

It should be noted that Wittgenstein and Schwarzenberg suffered defeats from Napoleon not only as a result of their mistakes. They were often not absolute commanders in the army, like Napoleon. Important people frequented the commander-in-chief's headquarters in anticipation of glory from the victory over the French ruler - Emperor Alexander, Grand Duke Constantine, Frederick William III, Franz I. All of them were military men and believed that the army could not do without “smart” advice. Together with them, a whole court of their advisers, generals, etc. arrived at headquarters. The headquarters was turned almost into a court salon.

The victories at Lützen, Bautzen and Dresden only strengthened Napoleon's faith in his star. He believed in his military superiority, underestimated the forces opposing him, and incorrectly assessed the fighting qualities of the enemy armies. It is clear that Wittgenstein and Schwarzenberg, as commanders, were much inferior to Napoleon, and the monarchs hostile to him understood even less in military strategy and tactics. However, Napoleon did not notice that new victories led to different consequences, for example, the victories at Austerlitz and Jena. The beaten Allied army only grew stronger after each defeat. The number of his enemies, their strength and determination to fight to a victorious end grew. Previously, victory in a decisive battle crushed the enemy army, the spirit of the country's political leadership, and predetermined the outcome of the campaign. The armies that fought with Napoleon's troops became different. In fact, Napoleon ceased to be a strategist in 1813, continuing to successfully resolve operational issues. His fatal mistake finally became clear after the so-called. "Battles of Nations".

September 1813 passed without significant battles, with the exception of another unsuccessful campaign of the French army under Marshal Ney to Berlin. At the same time, the position of the French army was deteriorating: a series of minor defeats, grueling marches and poor supplies led to significant losses. According to the German historian F. Mehring, in August and September the French emperor lost 180 thousand soldiers, mainly from disease and desertion.

At the beginning of October, the allied forces, strengthened by fresh reinforcements, went on the offensive against Napoleon, who held strong positions around Dresden. The troops were going to push his troops out of there with a wide outflanking maneuver from two sides at once. The Silesian Russian-Prussian army of Field Marshal Blucher (54-60 thousand soldiers, 315 guns) bypassed Dresden from the north and crossed the river. Elbe north of Leipzig. The Northern Prussian-Russian-Swedish army of Crown Prince Bernadotte (58-85 thousand people, 256 guns) also joined it. The Bohemian Austro-Russian-Prussian army of Field Marshal Schwarzenberg (133 thousand, 578 guns) left Bohemia, bypassed Dresden from the south and also moved towards Leipzig, going behind enemy lines. The theater of military operations moved to the left bank of the Elbe. In addition, already during the battle, the Polish Russian Army of General Bennigsen (46 thousand soldiers, 162 guns) and the 1st Austrian Corps Colloredo (8 thousand people, 24 guns) arrived. In total, the allied forces ranged from 200 thousand (October 16) to 310-350 thousand people (October 18) with 1350-1460 guns. The commander-in-chief of the allied armies was the Austrian field marshal K. Schwarzenber, he was subordinate to the advice of three monarchs. The Russian forces were led by Barclay de Tolly, although Alexander regularly intervened.

The French emperor, leaving a strong garrison in Dresden and setting up a barrier against the Bohemian army of Schwarzenberg, moved troops to Leipzig, where he first wanted to defeat the armies of Blucher and Bernadotte. However, they avoided battle, and Napoleon had to deal with all the allied armies at the same time. Near Leipzig, the French ruler had 9 infantry corps (about 120 thousand bayonets and sabers), the Imperial Guard (3 infantry corps, a cavalry corps and an artillery reserve, up to 42 thousand people in total), 5 cavalry corps (up to 24 thousand) and the Leipzig garrison (about 4 thousand soldiers). In total, Napoleon had approximately 160-210 thousand bayonets and sabers, with 630-700 guns.

Location of forces. On October 15, the French emperor deployed his forces around Leipzig. Moreover, most of his army (about 110 thousand people) was located south of the city along the Pleise River, from Connewitz to the village of Markleiberg, then further east through the villages of Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz to Holzhausen. 12 thousand General Bertrand's corps at Lindenau covered the road to the west. Units of Marshals Marmont and Ney (50 thousand soldiers) were stationed in the north.

By this time, the Allied armies had about 200 thousand bayonets and sabers in stock. Bennigsen's Polish army, Bernadotte's Northern army and Colloredo's Austrian corps were just arriving at the battlefield. Thus, at the beginning of the battle, the Allies had a slight numerical superiority. According to the plan of Commander-in-Chief Karl Schwarzenberg, the main part of the Allied forces was supposed to overcome the French resistance near Connewitz, pass through the swampy lowland between the Weisse-Elster and Pleisse rivers, bypass the enemy’s right flank and cut the shortest western road to Leipzig. About 20 thousand soldiers under the leadership of the Austrian Marshal Giulai were to attack the western suburb of Leipzig, Lindenau, and Field Marshal Blücher was to attack the city from the north, from Schkeuditz.

After objections from the Russian emperor, who pointed out the difficulty of moving through such territory (rivers, swampy lowlands), the plan was slightly changed. To implement his plan, Schwarzenberg received only 35 thousand Austrians. The 4th Austrian corps of Klenau, the Russian forces of General Wittgenstein and the Prussian corps of Field Marshal Kleist, under the general leadership of General Barclay de Tolly, were to attack the enemy head-on from the southeast. As a result, the Bohemian army was divided by rivers and swamps into 3 parts: in the west - the Austrians of Giulai, the second part of the Austrian army attacked in the south between the Weisse-Elster and Pleisse rivers, and the rest of the troops under the command of the Russian general Barclay de Tolly - in the southeast.

October 16. At about 8 o'clock in the morning, the Russian-Prussian forces of General Barclay de Tolly opened artillery fire on the enemy. Then the vanguard units went on the attack. Russian and Prussian forces under the command of Field Marshal Kleist occupied the village of Markleyberg around 9.30, which was defended by Marshals Augereau and Poniatowski. The enemy drove the Russian-Prussian troops out of the village four times, and four times the allies again took the village by storm.

The village of Wachau, located to the east, where units were stationed under the command of the French Emperor Napoleon himself, was also taken by the Russian-Prussians under the overall command of Duke Eugene of Württemberg. True, due to losses from enemy artillery shelling, the village was abandoned by noon.

Russian-Prussian forces under the overall command of General Andrei Gorchakov and Klenau's 4th Austrian Corps attacked the village of Liebertwolkwitz, which was defended by the infantry corps of Lauriston and MacDonald. After a fierce battle for every street, the village was captured, but both sides suffered significant losses. After reserves approached the French, the allies were forced to leave the village by 11 o'clock. As a result, the Allied offensive was unsuccessful, and the entire front of the anti-French forces was so weakened by the battle that they were forced to defend their original positions. The offensive of the Austrian troops against Connewitz also did not bring success, and in the afternoon Karl Schwarzenberg sent an Austrian corps to help Barclay de Tolly.

Napoleon decides to launch a counteroffensive. At approximately 3 o'clock in the afternoon, up to 10 thousand French cavalrymen under the command of Marshal Murat made an attempt to break through the central positions of the Allies near the village of Wachau. Their attack was prepared by an artillery attack from 160 guns. Murat's cuirassiers and dragoons crushed the Russian-Prussian line, overthrew the Guards Cavalry Division and broke through the Allied center. Napoleon even considered that the battle was won. The French cavalrymen managed to break through to the hill on which the allied monarchs and Field Marshal Schwarzenberg were located, but were driven back thanks to a counterattack by the Life Guards Cossack Regiment under the command of Colonel Ivan Efremov. The Russian Emperor Alexander, realizing earlier than others that a critical moment had arrived in the battle, ordered the Sukhozanet battery, Raevsky's division and the Prussian Kleist brigade to be thrown into battle. The offensive of the 5th French Infantry Corps of General Jacques Lauriston on Guldengossa also ended in failure. Schwarzenberg transferred reserve units to this position under the leadership of Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich.

The offensive of the forces of the Austrian Marshal Giulai (Gyulay) on Lidenau was also repelled by the French General Bertrand. Blucher's Silesian Army achieved serious success: without waiting for the approach of the Northern Army of the Swedish Crown Prince Bernadotte (he hesitated, trying to save his forces to capture Norway), the Prussian field marshal gave the order to launch an offensive. Near the villages of Wiederitz and Mökern, his units encountered fierce enemy resistance. Thus, the Polish general Jan Dombrowski, who was defending Wiederitz, held his position all day, fighting off Russian troops under the command of General Langeron. 20 thousand The corps of the Prussian general York, after a series of attacks, captured Mökern, which was defended by Marmont’s corps. The Prussians showed great courage in this battle. Blucher's army broke through the front of the French troops north of Leipzig.

The first day did not reveal any winners. However, the battle was very fierce and losses on both sides were significant. On the night of October 16–17, fresh armies of Bernadotte and Bennigsen approached Leipzig. The Allied forces had an almost double numerical advantage over the forces of the French Emperor.

Position of troops on October 16, 1813.

17 October. There were no significant battles on October 17; both sides collected the wounded and buried the dead. Only in the northern direction, the army of Field Marshal Blucher took the villages of Oitritzsch and Golis, coming close to the city. Napoleon pulled his troops closer to Leipzig, but did not leave. He hoped to conclude a truce, and he also counted on the diplomatic support of his “relative” - the Austrian emperor. Through the Austrian general Merfeld, who was captured at Connewitz, late at night on October 16, Napoleon conveyed his truce terms to the enemies. However, they didn’t even answer.

October 18. At 7 a.m., Commander-in-Chief Karl Schwarzenberg gave the order to go on the offensive. The French troops fought desperately, villages changed hands several times, they fought for every street, every house, every inch of land. So, on the left flank of the French, Russian soldiers under the command of Langeron captured the village of Shelfeld from the third attack, after a terrible hand-to-hand fight. However, reinforcements sent by Marshal Marmont drove the Russians out of their position. A particularly fierce battle raged near the village of Probstheid, in the center of the French positions. By 15:00 the corps of General Kleist and General Gorchakov were able to break into the village and began to capture one house after another. Then the Old Guard and the Guards artillery of General Drouot (about 150 guns) were thrown into the battle. French troops drove the allies out of the village and attacked the main forces of the Austrians. Under the blows of the Napoleonic guard, the allied lines “crackled.” The French advance was stopped by artillery fire. In addition, Napoleon was betrayed by the Saxon division, and then by the Württemberg and Baden units.

The fierce battle continued until nightfall, the French troops held all the main key positions, but in the north and east the Allies came close to the city. The French artillery used up almost all its ammunition. Napoleon gave the order to retreat. Troops under the command of Macdonald, Ney and Lauriston remained in the city to cover the retreat. The retreating French army had only one road to Weißenfels at its disposal.

Position of troops on October 18, 1813.

October 19. The Allies planned to continue the battle to force the French to surrender. Reasonable proposals from the Russian sovereign to cross the Pleise River and Prussian Field Marshal Blücher to allocate 20 thousand cavalry to pursue the enemy were rejected. At dawn, realizing that the enemy had cleared the battlefield, the Allies moved towards Leipzig. The city was defended by soldiers of Poniatowski and MacDonald. Loopholes were made in the walls, arrows were scattered and guns were placed on the streets, among the trees and gardens. Napoleon's soldiers fought desperately, the battle was bloody. Only by the middle of the day did the Allies manage to take possession of the outskirts, knocking out the French from there with bayonet attacks. During the confusion surrounding the hasty retreat, sappers blew up the Elsterbrücke Bridge, located in front of the Randstadt Gate. At this time, about 20-30 thousand soldiers of MacDonald, Poniatowski and General Lauriston still remained in the city. Panic began, Marshal Jozef Poniatowski tried to organize a counterattack and an organized retreat, was wounded twice and drowned in the river. General Lauriston was captured, Macdonald barely escaped death by swimming across the river, and thousands of French were captured.

Battle of Grimm's Gate on October 19, 1813. Ernst Wilhelm Strasberger.

Results of the battle

The Allied victory was complete and had pan-European significance. Napoleon's new army was completely defeated, the second campaign in a row (1812 and 1813) ended in defeat. Napoleon took the remnants of the army to France. Saxony and Bavaria went over to the side of the Allies, and the Rhineland Union of German states, which was subject to Paris, collapsed. By the end of the year, almost all the French garrisons in Germany capitulated, so Marshal Saint-Cyr surrendered Dresden. Napoleon was left alone against almost all of Europe.

The French army lost approximately 70-80 thousand people near Leipzig, of which approximately 40 thousand were killed and wounded, 15 thousand prisoners, another 15 thousand were captured in hospitals, up to 5 thousand Saxons and other German soldiers surrendered.

The losses of the allied armies amounted to 54 thousand killed and wounded, of which about 23 thousand Russians, 16 thousand Prussians, 15 thousand Austrians and only 180 Swedes.

Ctrl Enter

Noticed osh Y bku Select text and click Ctrl+Enter

This was the end of Napoleon Bonaparte. He remained the ruler of a large part of Europe (directly, through relatives or dependent rulers), enjoyed authority in his homeland and did not lose either his talents as a commander or his ambitions as a conqueror. At the same time, France’s potential still fully allowed for revenge, and the emperor’s opponents rushed to eradicate this possibility.

The Sixth Coalition and the Young Guard

Napoleon treated each of his rivals in 1813 with a degree of contempt. He feared Russia more than anyone, but he knew that not only his army suffered in the campaign of 1812 - the Russians also lost up to a third of their soldiers and had worse opportunities to replenish their army ranks. Napoleon also knew that he was categorically against the continuation of the war (and soon the famous commander died). The emperor did not value the Prussians and Austrians at all and refused on principle to conduct peace negotiations, hoping for victory.

The beginning of 1813 did indeed bring significant successes to France. But the problem was that Napoleon's position after the Russian defeat changed for the worse:

- the “old guard” remained forever under Borodino; 18-20 year olds were recruited into the army, and the combat effectiveness of this “Young Guard” was doubtful;

- the dependent monarchs learned that the Emperor of the French was not invincible;

- a liberation movement spread in the conquered territories, caused, among other things, by military exactions;

- France had to fight not with one country, but with a bloc.

This bloc is known as the Sixth Anti-French Coalition. It included Russia, England, Austria, Prussia, Sweden and several other German states.

France also had allies, in particular from among the same Germans. But her block was less reliable. It is characteristic that representatives of many nations (in particular, the Germans and Poles) fought for both sides. That is why the battle of October 1813 near Leipzig was called the “Battle of the Nations.”

Defeat with Honor

The battle took place during October 16-19, 1813. The French troops were personally commanded by the Emperor, the commander-in-chief of the Allied forces was the Austrian Field Marshal Schwarzenberg, in whose decisions (especially at the planning stage) Alexander 1 intervened.

The balance was initially not in favor of the French - the coalition forces were one third larger. However, the first day can be considered victorious for Napoleon - his troops completed all the assigned tasks, and at the same time had fewer losses than the coalition.

Then the situation changed. The allies received reinforcements 4 times larger than what came to the French. In the battle of October 18, the Saxon, Württemberg and Baden units that fought for Napoleon went over to the enemy, and this decided the outcome of the battle.

The French desperately defended Leipzig, but were forced to abandon it on October 19. The retreat was not prepared (Napoleon was counting on victory), and this increased the number of losses. The sappers were ordered to blow up the bridges behind the retreating army, but they were too hasty, and several thousand people died in the water and from their own mines.

In general, the French lost 70-80 thousand people (including killed, wounded, prisoners and those who went over to the enemy), the coalition - 55 thousand. In total, up to 500 thousand people took part in the battle and it remained the largest in human history until the beginning of the First World War war.

Everlasting memory

The “Battle of the Nations” also did not mark the end of Napoleon, but brought it closer. He was running out of resources to mobilize. The French, losing their sons, were unhappy with the emperor. Resistance intensified in the lands conquered by France.

In 1913, a grandiose memorial dedicated to the “battle of the nations” was erected near Leipzig. The coalition countries issued coins, stamps, and commemorative medals in her honor.

But it turned out that popular rumor often preserved the memory of the vanquished. In particular, in Poland they honor the memory of the dashing cavalryman Yu. Poniatovsky, who served Napoleon for the revival of Poland and died near Leipzig. The exploits of another Pole on the French side, General Jan Dąbrowski, became the basis of the "Dąbrowski Mazurka", the current anthem of Poland.

And dozens of Russian conquerors of Napoleon ended up on Senate Square and in the Nerchinsk mines. However, this is a completely different story...